Medication Disposal Guide

Find Your Safe Disposal Method

Based on FDA guidelines, determine the best way to dispose of your expired medications.

Every year, millions of unused or expired pills sit in bathroom cabinets, kitchen drawers, and medicine chests across the U.S. Most people don’t know what to do with them-so they just leave them there. Or worse, they flush them down the toilet or toss them in the trash. That’s not just careless-it’s dangerous. The FDA has clear, science-backed rules for disposing of expired medications, and following them can prevent overdoses, protect water supplies, and keep drugs out of the hands of kids or strangers. Here’s how to do it right.

Why Proper Disposal Matters

| Risk | Impact | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Accidental Poisoning | Over 50,000 ER visits annually from children or seniors taking wrong meds | FDA 2023 Consumer Update |

| Drug Misuse | 13,470 overdose deaths in 2022 linked to unused prescription opioids | National Institute on Drug Abuse |

| Water Contamination | 0.0001% of pharmaceuticals in U.S. waterways come from flushing | USGS 2024 National Water Quality Assessment |

| Environmental Harm | Flushing affects aquatic life; EPA says it’s preventable | EPA Household Medication Disposal Guidance, 2023 |

Think about it: if you don’t dispose of your old painkillers, someone else might find them. A teenager could grab them from a cabinet. An elderly neighbor might accidentally mix them with their own meds. Or, over time, chemicals from crushed pills in landfills can leach into groundwater. The FDA is the U.S. agency responsible for regulating drug safety and disposal guidelines says the safest option isn’t flushing, isn’t tossing, and isn’t hoarding-it’s take-back.

The Three Approved Methods

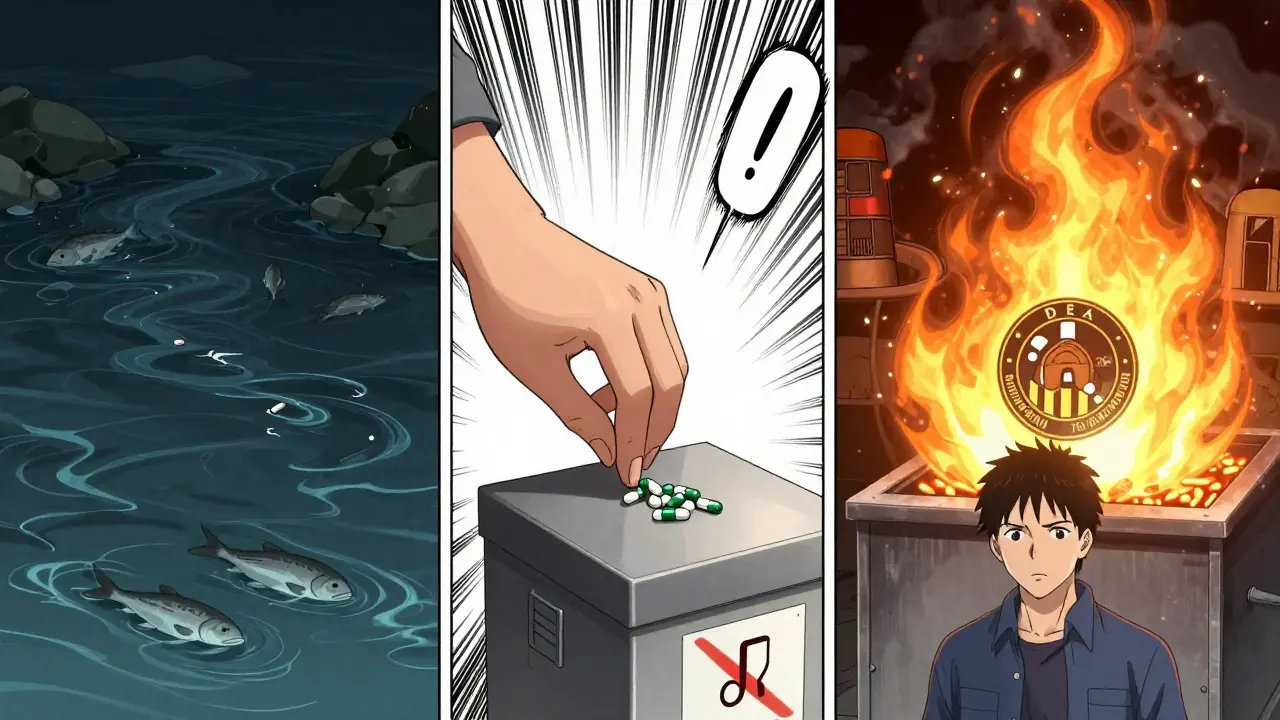

The FDA doesn’t leave you guessing. They’ve laid out a clear hierarchy: one best method, one backup, and one last resort.

1. Use a Drug Take-Back Location (Best Option)

This is the gold standard. The DEA authorizes and oversees permanent medication collection sites across the U.S. has set up over 14,352 permanent collection points at pharmacies, hospitals, and police stations as of January 2025. You can drop off pills, patches, liquids, even syringes-no questions asked. These sites are secure, monitored, and destroy medications safely.

Most major pharmacy chains offer this. Walmart operates 4,700 take-back kiosks in all U.S. locations. CVS has invested $15 million in mail-back and kiosk programs. Even small-town pharmacies often have a box near the pharmacy counter labeled “Drug Take-Back.”

Want to find one near you? Visit the DEA’s website or call your local pharmacy. You don’t need to be a customer. No ID needed. No cost. Just bring your expired meds and drop them in.

The results speak for themselves: take-back programs achieve a 99.8% proper disposal rate. That’s nearly perfect.

2. Mail-Back Envelopes (Great Backup)

If there’s no take-back site within 15 miles, the FDA recommends prepaid mail-back envelopes. These are specially designed to be tamper-proof and safe for shipping. Companies like DisposeRx and Sharps Compliance provide these under USPS regulations.

Here’s how they work: you fill the envelope with your expired meds, seal it, and drop it in any mailbox. The company picks it up and disposes of it properly. Many insurance providers, including Express Scripts, offer them for free. In their 2024 analysis of 287,000 users, 94.2% said they were satisfied.

Costs range from $2.15 to $4.75 if you buy them yourself, but if you’re on Medicare, Medicaid, or a large insurer, you’re likely eligible for free envelopes. Ask your pharmacist.

3. Home Disposal (Only If You Have No Other Choice)

If you can’t get to a take-back site or mail-back envelope, and your meds aren’t on the flush list, here’s what to do-exactly:

- Remove personal info from the bottle. Use a permanent marker to black out your name, prescription number, and dosage. Or wipe it off with rubbing alcohol.

- Mix with something unpalatable. Use coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt. The FDA says use a 1:1 ratio-equal parts meds and substance. Why? So if someone digs through your trash, they won’t want to eat it.

- Seal it in a container. Use a plastic bag or jar with a tight lid. The FDA recommends plastic at least 0.5mm thick. Don’t just dump it in a paper bag.

- Put it in the trash. Not the recycling bin. The trash.

- Recycle the empty container after you’ve removed all labels. Most plastic bottles can be recycled.

This method is messy, but it’s better than flushing. And it works-if you do it right. A 2023 FDA study found that 12.7% of home disposal attempts failed, mostly because people didn’t mix the meds properly or didn’t seal the container.

The Flush List: What You Can and Can’t Flush

Here’s the big exception: some drugs are so dangerous if misused that the FDA says you can flush them-if you have no other option.

There are exactly 13 active ingredients on the FDA Flush List a list of high-risk medications that may be flushed only when take-back isn't available. As of October 2024, it includes:

- Fentanyl (patches and tablets)

- Oxycodone

- Hydrocodone

- Buprenorphine

- Morphine

- Oxymorphone (removed from list in 2024)

- Tapentadol

- Meperidine

- Hydromorphone

- Alprazolam (Xanax)

- Clonazepam

- Dextroamphetamine

- Methylphenidate

Notice anything? Most are opioids or controlled substances. These are the drugs most often stolen, sold, or accidentally taken by children. Flushing them immediately removes the risk.

But here’s the catch: flushing should only happen if you have no other option. The EPA says flushing should never be the first choice-even for these drugs-because it adds to water pollution. The FDA says “readily available” take-back means within 15 miles or a 30-minute drive. If you’re in rural Alabama or northern Maine and your nearest drop-off is 50 miles away, then flushing is acceptable.

Don’t flush anything else. Not antibiotics. Not blood pressure pills. Not vitamins. Just the 13 on the list. And if you’re unsure? Ask your pharmacist.

What You Should Never Do

There are three big mistakes people make:

- Don’t pour liquids down the sink. Liquid medications can leak, spill, or be accidentally ingested. Always mix them with coffee grounds or cat litter first.

- Don’t flush non-Flush List meds. A 2024 Consumer Reports survey found 34% of people flushed pills they thought were safe to flush. That’s wrong. Most meds don’t belong in water.

- Don’t leave them in the original bottle. If you throw away a bottle with your name on it, someone could steal it-or you could accidentally give it to a new doctor later. Always remove labels.

What’s Changing in 2025

The system is getting better. In March 2025, the DEA announced plans to expand permanent take-back sites to 20,000 locations nationwide. The EPA is launching a $37.5 million grant program to help rural areas build collection infrastructure. And the FDA is pushing for 90% take-back usage by 2030.

Meanwhile, mail-back programs are growing fast. DisposeRx now holds 48% of the mail-back market, thanks to partnerships with pharmacies and insurers. And in 2024, the DEA’s National Take-Back Day collected over 1 million pounds of meds-up nearly 29% from the year before.

It’s clear: the system is evolving. But you don’t have to wait. Right now, you can take action.

What to Do Today

Here’s your simple plan:

- Check your medicine cabinet. Pull out anything expired, unused, or no longer needed.

- Look at the label. Does it have one of the 13 Flush List ingredients? If yes, and you can’t get to a take-back site within 15 miles, flush it. Otherwise, hold onto it.

- Find a take-back location. Use the DEA’s website or call your local CVS, Walgreens, or police station.

- Drop it off. No appointment needed. No cost.

- If you can’t go, request a mail-back envelope from your pharmacy or insurer.

- If all else fails, follow the 5-step home disposal method above.

It takes 10 minutes. And it could save a life.

Can I flush any expired medication if I don’t have a take-back option?

No, only the 13 specific drugs on the FDA Flush List can be flushed-and only if you have no other option. Flushing anything else pollutes water and is against EPA guidelines. If you can’t get to a take-back site, use a mail-back envelope or follow the home disposal steps: mix with coffee grounds, seal in a plastic container, and throw it in the trash.

Are take-back programs really safe? I’m worried about theft.

Yes, they’re designed to be secure. DEA-authorized collection sites are monitored, locked, and emptied regularly. In fact, 42.7% of medications collected in 2023 were opioids or benzodiazepines-drugs that are often stolen from homes. Take-back programs prevent that. The DEA tracks every collection, and disposal is done through incineration, which destroys the drugs completely.

What if I live in a rural area with no take-back sites nearby?

You’re not alone. About 31% of rural residents report no take-back site within 25 miles. In that case, the FDA allows you to use a mail-back envelope or follow home disposal steps. Many pharmacies and insurers now offer free mail-back kits. Ask your pharmacist or check your insurance website. If you can’t get one, mix your meds with coffee grounds, seal them in a plastic container, and throw them in the trash.

Can I dispose of needles or syringes in the same way?

No. Needles and sharps require special handling. Most take-back sites accept them in sealed sharps containers. If you have them, ask your pharmacy if they have a sharps disposal program. Some mail-back envelopes also accept sharps. Never put loose needles in the trash. Use a rigid plastic container like a laundry detergent bottle, seal it, label it “SHARPS,” and follow local disposal rules.

Do I need to clean out my medicine cabinet every year?

It’s a good habit. The FDA recommends reviewing your meds at least once a year. Look for expiration dates, changes in color or smell, and unused prescriptions. If you’ve switched doctors, changed medications, or stopped a treatment, those pills should go. A clean cabinet reduces confusion and risk. Plus, many pharmacies offer free disposal events twice a year-April and October. Check the DEA’s calendar.

Next Steps

If you’ve got expired meds sitting around, don’t wait. Take 10 minutes today and find your nearest drop-off location. If you’re in a rural area, request a mail-back envelope. If you’re unsure about a specific drug, call your pharmacist. They’re trained to help. And if you’re helping an elderly parent or a young adult, make sure they know how to do it right. The system is there. You just need to use it.