Wilson’s disease isn’t something most people have heard of-until it hits their family. It starts quietly: a teenager with unexplained fatigue, an adult with abnormal liver tests, or someone suddenly struggling to hold a cup without shaking. What no one realizes at first is that their body is drowning in copper. Not from eating too many nuts or shellfish, but because of a broken gene that stops the liver from flushing out the metal. Left untreated, this buildup destroys the liver, scrambles the brain, and can be fatal. But here’s the critical part: Wilson’s disease is treatable. And the key is understanding how copper moves-and gets stuck-in the body.

How Copper Goes Wrong in Wilson’s Disease

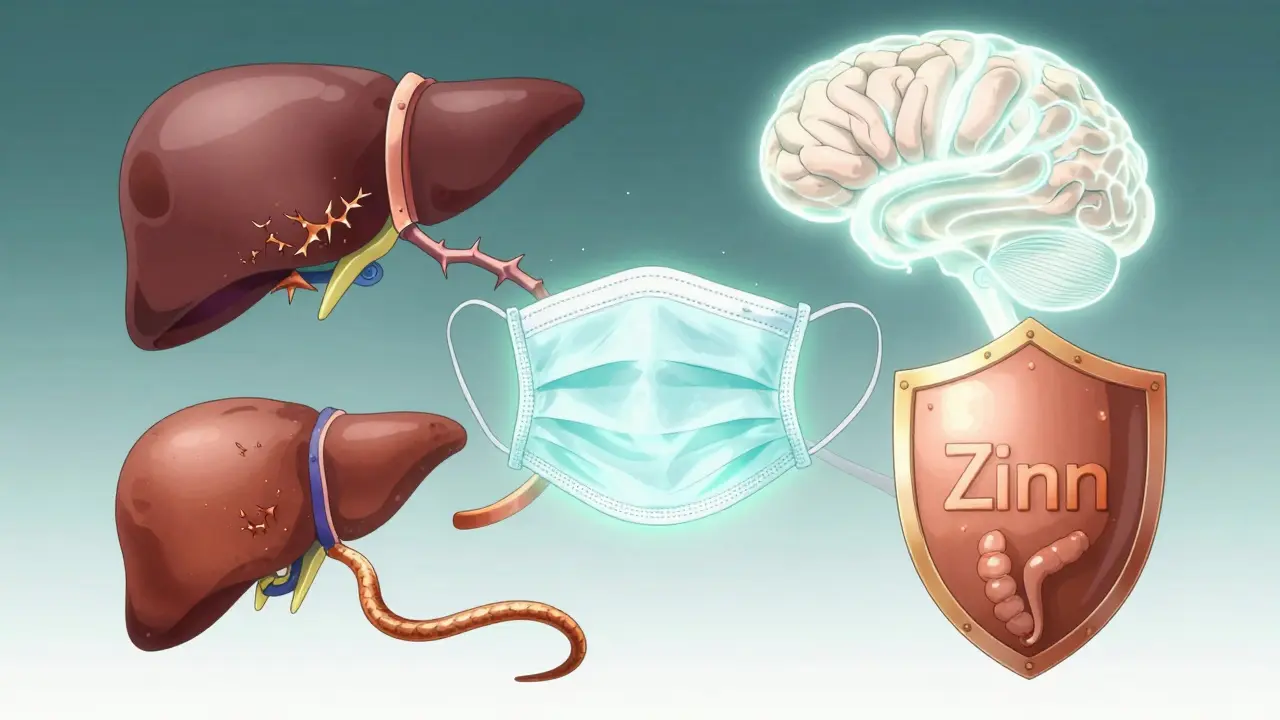

Every person needs copper. It’s in your enzymes, your nerves, your blood. But your body doesn’t make it-you get it from food. Your small intestine absorbs it, your liver takes it in, and normally, your liver does two things: it wraps most of it into a protein called ceruloplasmin (which carries copper safely through your blood), and it dumps the rest into bile to be pooped out. In Wilson’s disease, that second step breaks down.

The problem starts with a mutation in the ATP7B gene. This gene makes a protein that acts like a copper pump in liver cells. When it’s broken, copper piles up inside the liver. At first, the liver tries to protect itself by locking copper away with metallothionein, a storage protein. But once those storage sites fill up, copper leaks into the bloodstream as free copper-the dangerous kind. That’s when things get serious.

This free copper doesn’t just sit around. It travels to the brain, especially the basal ganglia, which controls movement. It settles in the eyes, forming greenish-brown rings around the cornea called Kayser-Fleischer rings-visible only with an eye exam. It damages the kidneys and can cause anemia. And because ceruloplasmin isn’t being made properly, blood tests show low levels of it-often below 20 mg/dL (normal is 20-50). That’s one of the first red flags doctors look for.

Why Diagnosis Is So Hard-and So Critical

Wilson’s disease is rare. About 1 in 30,000 people have it. That’s part of why it’s missed. Symptoms look like other, more common conditions. Liver problems? Could be hepatitis. Tremors and mood swings? Maybe Parkinson’s or anxiety. In fact, a 2022 survey of patients found that 68% were misdiagnosed, often for years. One patient spent seven years being treated for autoimmune hepatitis before a 24-hour urine copper test showed 380 μg-way above the normal 40 μg.

Diagnosis isn’t one test. It’s a puzzle. Doctors look at:

- Serum ceruloplasmin (low in 85-90% of cases)

- 24-hour urinary copper (over 100 μg in liver-dominant cases, but can be lower in neurological forms)

- Slit-lamp eye exam for Kayser-Fleischer rings (present in 95% of those with neurological symptoms)

- Liver biopsy showing copper levels over 250 μg/g dry weight

- Genetic testing for ATP7B mutations

There’s a scoring system that adds these up. A score of 4 or higher is diagnostic. But here’s the catch: kids under five often don’t have the eye rings yet, and their ceruloplasmin can be low for normal reasons. That’s why genetic testing is becoming the gold standard-especially when symptoms are unclear.

Chelation Therapy: Pulling Copper Out of the Body

Once diagnosed, treatment starts immediately. The goal? Stop copper from building up and remove what’s already there. That’s where chelation therapy comes in. Chelators are drugs that bind to copper like a claw, pulling it out of tissues and letting your kidneys flush it away in urine.

The two main first-line chelators are D-penicillamine and trientine. D-penicillamine has been used since the 1950s. It’s cheap-about $300 a month in the U.S.-but it has a nasty side effect profile. About 20-50% of patients get worse neurologically in the first few weeks. Some develop skin rashes, kidney damage, or even lupus-like symptoms. Trientine, introduced later, is gentler on the nervous system. It doesn’t cause as much neurological worsening, but it’s more expensive-around $1,850 a month. Many patients switch to trientine after an initial reaction to penicillamine.

There’s a third option: zinc. Zinc doesn’t remove copper-it stops you from absorbing it. It works by triggering your gut to make metallothionein, which traps copper in your intestines so it gets pooped out instead of absorbed. Zinc acetate (brand name Galzin) is usually used after initial chelation to keep copper levels stable. It’s safer long-term, with fewer side effects. But it doesn’t pull out existing copper-it just blocks new intake. That’s why you can’t start with zinc if you’re already overloaded.

What Patients Really Go Through

Living with Wilson’s disease means constant monitoring. Every three months: liver tests, serum free copper checks. Every six months: 24-hour urine copper. And you have to take your meds on an empty stomach-no food for at least an hour before and after. That’s hard to stick to, especially if you’re a student or working full-time. A 2022 patient survey found that 35% missed doses, mostly because of nausea, metallic taste, or just forgetting.

Diet matters too. You’re told to avoid foods high in copper: shellfish, liver, nuts, chocolate, mushrooms, soy, and even some tap water (if it runs through copper pipes). But cutting these out without replacing nutrients can lead to deficiencies. Many patients end up on a multivitamin with zinc and vitamin B6 to help balance things out.

One patient, u/CopperFree on Reddit, switched from penicillamine to zinc after kidney problems. Within six months, his liver enzymes dropped from 145 to 38 U/L. Another, u/WilsonWarrior, had his tremors spike after starting penicillamine. His doctor added zinc and adjusted the dose-after three months, the shaking slowed. These aren’t rare stories. They’re the norm.

New Treatments on the Horizon

Chelation works-but it’s not perfect. That’s why researchers are pushing for better options. In 2023, a new drug called CLN-1357, a copper-binding polymer, showed an 82% drop in free serum copper in just 12 weeks-with no neurological worsening. That’s huge. Another drug, WTX101 (bis-choline tetrathiomolybdate), got breakthrough status from the FDA after a 2022 trial showed 91% success in preventing neurological decline, beating trientine’s 72%.

There’s even a gene therapy trial underway. Scientists are using a harmless virus to deliver a working copy of the ATP7B gene into liver cells. Early results in six patients were safe. It’s still early, but if it works, it could mean one-time treatment instead of lifelong pills.

In Europe, a new version of tetrathiomolybdate called Decuprate was approved in 2022 specifically for neurological Wilson’s disease. It crosses the blood-brain barrier better than older drugs, making it ideal for patients with tremors or speech problems.

Life After Diagnosis

Here’s the most important thing: if you catch Wilson’s disease early and stick to treatment, you can live a normal life. People on stable therapy have the same life expectancy as anyone else. Their livers heal. Their tremors fade. They go back to work, school, parenting. The key is consistency.

But if you wait? The damage can be permanent. Liver failure. Brain damage. Parkinson’s-like movement disorders that don’t improve even with treatment. That’s why screening siblings of diagnosed patients is so important. If one child has it, there’s a 25% chance their brother or sister does too.

And if you’re in a country with limited access to testing? The delay can be five years or more. That’s why raising awareness matters-not just among doctors, but among families who notice unexplained symptoms. A simple urine test, an eye exam, a blood draw. That’s all it takes to change a life.

What to Do If You Suspect Wilson’s Disease

If you or someone you know has:

- Unexplained liver enzyme elevations

- Tremors, stiffness, or trouble speaking

- Psychiatric symptoms like depression or impulsivity

- A family history of liver disease or unexplained neurological issues

Ask for a 24-hour urinary copper test and a ceruloplasmin blood test. Push for an eye exam if neurological symptoms are present. Don’t wait for a diagnosis to be obvious. Wilson’s disease doesn’t announce itself-it creeps in. But once you know, you can stop it.

There’s no cure yet. But there’s control. And for a disease that was once a death sentence, that’s everything.

9 Comments

Jane WeiDecember 17, 2025 AT 21:06

My cousin was diagnosed last year after years of being told it was just anxiety. Turns out her ceruloplasmin was 12. She’s on zinc now and finally sleeping through the night. No more shaking hands. Just takes discipline.

Josh PotterDecember 18, 2025 AT 04:16

Okay but why is this drug so expensive?? Trientine costs more than my rent. Meanwhile, my cousin in India gets it for $20 a month through some NGO. This system is broken. We’re literally charging people to not die. 🤡

CAROL MUTISODecember 19, 2025 AT 10:51

So we’re telling people to avoid nuts, chocolate, and shellfish… but the real villain is a broken gene? That’s like blaming someone for being allergic to air because they breathe too much. It’s not their fault. It’s biology. And yet we still act like they’re failing at life if they miss a dose. 😌

Radhika MDecember 20, 2025 AT 23:23

I work in a lab in Mumbai. We test 3-4 suspected Wilson’s cases every month. Most are teens with tremors. Parents think it’s stress. We do the 24-hour urine. Bam. Copper at 400+. It’s heartbreaking how late they come. Early detection saves lives. Get tested if you have family history.

Jigar shahDecember 21, 2025 AT 12:40

The ATP7B gene mutation is autosomal recessive, so both parents must be carriers. That’s why siblings of diagnosed patients have a 25% risk. Genetic screening should be routine in families with unexplained liver or neurological symptoms, especially in regions with high consanguinity. The scoring system is useful, but in children under five, genetic testing is the only reliable method. I’ve seen cases where ceruloplasmin was normal due to age-related variation, but the mutation was clear.

Also, zinc therapy isn’t just for maintenance-it’s the only safe long-term option for pediatric patients. Penicillamine’s neurotoxicity in young brains is underreported. The fact that CLN-1357 showed zero neurological worsening in trials is a game-changer. We need more funding for these next-gen chelators.

And yes, diet matters, but copper from pipes is negligible unless water sits for hours. Boiling doesn’t help-it concentrates minerals. Better to flush taps before drinking. Most patients overestimate dietary risk. The real issue is absorption, not intake.

Also, the Kayser-Fleischer ring isn’t always visible without a slit-lamp. General ophthalmologists miss it. That’s why neurologists should request it explicitly. No excuse for delay.

Gene therapy is promising but still years away. For now, consistency with meds is the real cure. One patient I followed missed doses for six months, then came in with AST 210. Restarted zinc, liver normalized in four months. It’s not magic. It’s just chemistry. And patience.

Don’t let cost stop you. Some pharmaceutical assistance programs cover trientine. Ask your pharmacist. There are options. You’re not alone.

Kaylee EsdaleDecember 22, 2025 AT 00:27

My mom’s on zinc. She forgets to take it before meals. Now she eats a banana 20 mins before. Works. No more metallic taste. She says it’s like brushing your teeth-just a habit now. We all need to make it easy.

Pawan ChaudharyDecember 22, 2025 AT 05:27

My uncle had this. He thought he was just tired. Now he’s back coaching soccer. Took 18 months. But he’s alive. That’s the win. Keep going, people. You got this.

Linda CaldwellDecember 23, 2025 AT 23:13

They say Wilson’s is rare-but how many people are just misdiagnosed and never tested? I know three people who were told they had ‘chronic fatigue’ or ‘early Parkinson’s.’ Turns out? Copper overload. One guy got his diagnosis after his dog started barking at him every time he trembled. The dog sensed it before the doctors did. Animals know. We just don’t listen.

Kent PetersonDecember 24, 2025 AT 17:32

Wow. So… we’re spending billions on gene therapy for a disease that’s treatable with a $300 pill? And you’re telling me this isn’t just a conspiracy to sell expensive drugs? I mean, D-penicillamine’s been around since 1956! Why not just make it cheaper? Why not mandate testing in every liver panel? Why are we waiting for a miracle when we already have the cure? This isn’t science-it’s capitalism with a stethoscope.