Zollinger-Ellison syndrome — what to watch for and what to do

Too many ulcers, even while taking medicines? That’s a red flag. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) happens when a gastrinoma — a tumor that makes excess gastrin — forces your stomach to produce too much acid. That extra acid causes stubborn peptic ulcers, chronic diarrhea, and weight loss that won’t explain away.

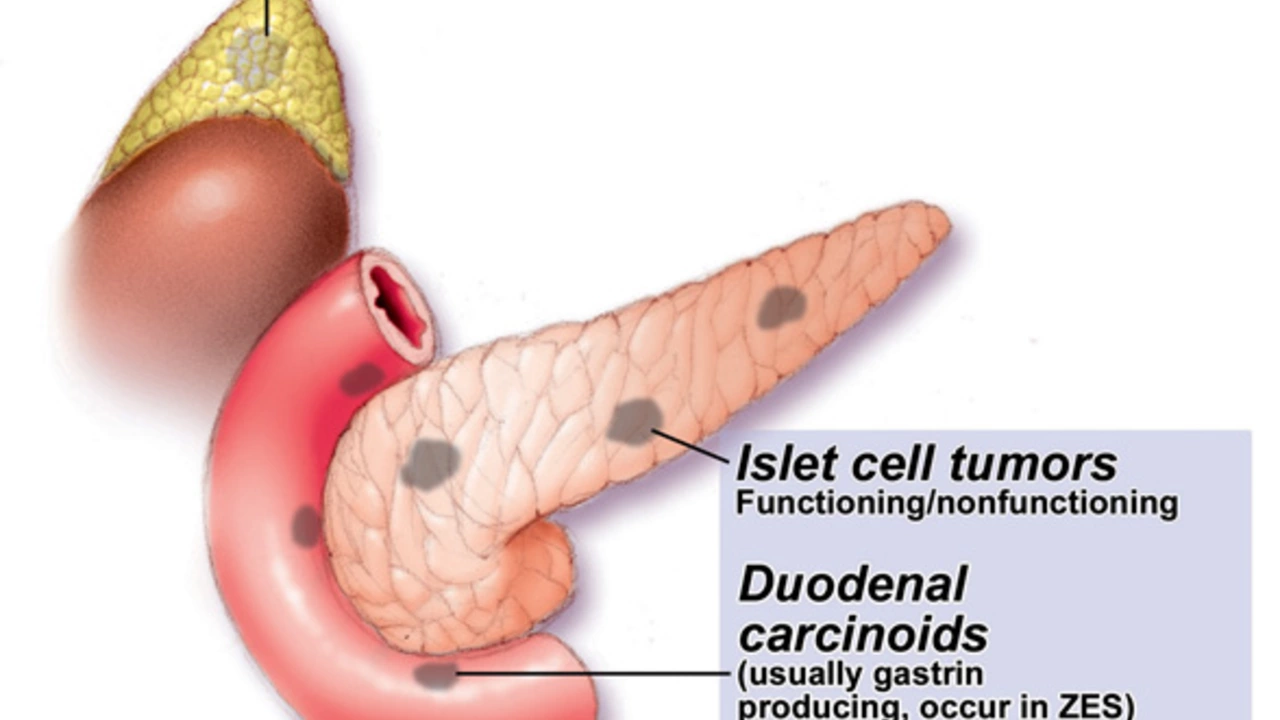

Gastrinomas most often sit in the pancreas or the duodenum. Around 20–25% of cases are tied to a genetic disorder called MEN1 (multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1). People usually notice symptoms between ages 30 and 60, though MEN1 can bring them earlier.

Common signs: severe recurrent ulcers, burning abdominal pain, watery diarrhea, acid reflux that won’t improve on regular treatment, unintended weight loss, and signs of bleeding or anemia. If ulcers show up in odd places (like the small intestine beyond the duodenum) or come back after treatment, ask whether ZES has been ruled out.

How doctors diagnose it

Testing starts with blood: a fasting gastrin level. Very high fasting gastrin (often above a few hundred pg/mL and sometimes >1,000 pg/mL) suggests a gastrinoma, but proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) raise gastrin too. Don’t stop PPIs on your own — discuss timing and risks with your doctor.

If fasting gastrin is unclear, doctors use the secretin stimulation test. In ZES, giving secretin causes a sharp rise in gastrin (an increase of about 120 pg/mL or more is usually considered positive). After biochemical tests, imaging looks for the tumor. CT or MRI of the abdomen is common. For small or hard-to-find tumors, somatostatin receptor imaging (Ga-68 PET or Octreoscan) finds more cases.

Treatment and follow-up — straightforward steps

First goal: control acid. High-dose PPIs (for example, omeprazole or pantoprazole) usually work well and are started quickly. If the tumor is localized and operable, surgery to remove the gastrinoma can cure ZES. When tumors have spread, options include somatostatin analogs (octreotide or lanreotide) to slow tumor growth, targeted therapies, and liver-directed treatments for metastases.

Follow-up is key: regular fasting gastrin checks, symptom tracking, and periodic imaging. If MEN1 is suspected, genetic testing and screening for other endocrine tumors are needed.

Practical tips: keep a short symptom diary (ulcer flares, diarrhea, bleeding), bring a full list of medicines to appointments, and ask clear questions like “Could this be a gastrinoma?” or “Should I test for MEN1?” If your clinician suggests pausing PPIs for tests, ask how to do it safely. Work with both a gastroenterologist and an endocrinologist — ZES sits between those specialties.

ZES is rare, but it’s worth checking when ulcers behave badly. Early diagnosis cuts the risk of serious complications such as perforation, heavy bleeding, and malabsorption. Keep asking questions until you get clear answers — that’s how you steer care in the right direction.

In my recent exploration, I delved into the role of Famotidine in tackling Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome. Famotidine, a type of H2 blocker, plays a pivotal role in treating this rare condition, which results in the overproduction of stomach acid. It works by reducing the amount of acid produced by the stomach, thereby alleviating symptoms and preventing complications. Its effectiveness and limited side effects make it a popular choice among medical professionals. So, if you or a loved one are dealing with Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome, Famotidine could be a valuable part of the treatment plan.