SAH Medication Strategy Guide

Nimodipine

Prevents vasospasm and delayed cerebral ischemia

Labetalol

Controls hypertension while preserving cerebral perfusion

Levetiracetam

Seizure prophylaxis

Tranexamic Acid

Reduces re-bleeding risk before aneurysm securement

Acetaminophen

Pain control without affecting platelet function

Key Takeaways

- Medication is essential for preventing vasospasm, controlling blood pressure, and managing pain after a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).

- Nimodipine, a calcium channel blocker, is the cornerstone drug for reducing delayed cerebral ischemia.

- Antihypertensives, antiepileptics, and antifibrinolytics each address specific complications and are selected based on Hunt‑Hess grade and imaging findings.

- Careful dosing, regular monitoring, and early detection of side‑effects improve outcomes and shorten intensive‑care stay.

- Coordinated care between neurosurgeons, intensivists, and pharmacists is crucial for individualized medication plans.

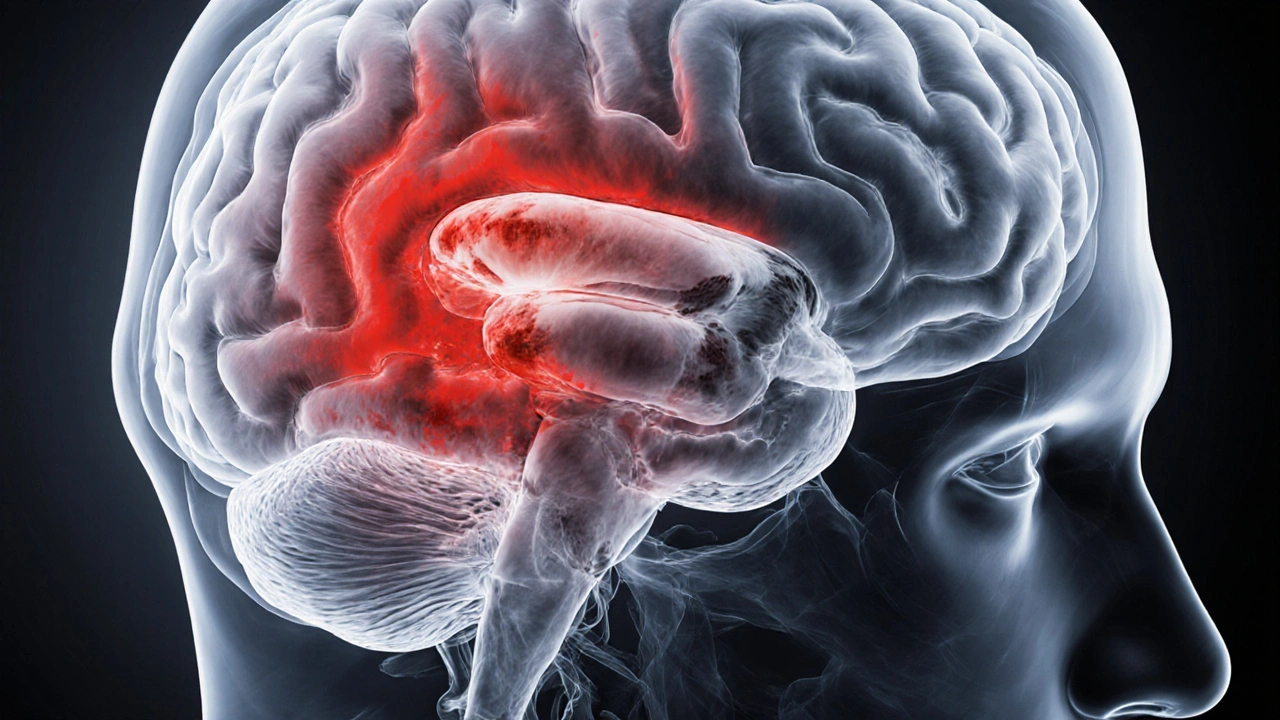

What Is Subarachnoid Hemorrhage?

When blood leaks into the space between the brain and the thin membrane covering it, the condition is called subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). The bleeding most often originates from a ruptured aneurysm, but trauma or arteriovenous malformations can also be culprits. The sudden surge of blood raises intracranial pressure, irritates the meninges, and can trigger a cascade of secondary problems such as vasospasm, hydrocephalus, and seizures.

Patients typically present with a "worst headache of their life," neck stiffness, nausea, and sometimes a brief loss of consciousness. Prompt imaging-non‑contrast CT within the first 6hours, followed by CT‑angiography-confirms the diagnosis and identifies the source.

Why Medication Matters After SAH

Even after the aneurysm is secured by surgical clipping or endovascular coiling, the brain remains vulnerable. The most dreaded delayed complication is cerebral vasospasm, a narrowing of arteries that can cause ischemic stroke days after the bleed. Medications target three main goals:

- Preventing vasospasm and delayed cerebral ischemia.

- Stabilising systemic parameters (blood pressure, heart rate) that influence cerebral perfusion.

- Managing symptomatic burdens-pain, seizures, and hydrocephalus-while minimising drug‑related toxicity.

Evidence from randomized trials and large registry data (e.g., the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial) shows that early, protocol‑driven medication reduces mortality from 30% to under 20% in high‑grade patients.

Core Medications and Their Roles

Below is a practical breakdown of the drugs most frequently prescribed in the acute phase (first 14days) of SAH.

| Medication | Primary Purpose | Typical Dose & Route | Key Side‑Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nimodipine | Prevent vasospasm / delayed cerebral ischemia | 60mg orally every 4h (or 30mg NG tube q2h if nausea) | Hypotension, dizziness, flushing |

| Labetalol | Control hypertension while preserving cerebral perfusion | 20mg IV bolus, repeat q10min up to 300mg | Bradycardia, bronchospasm (in asthmatics) |

| Levetiracetam | Seizure prophylaxis | 500mg IV/PO q12h (adjust for renal function) | Irritability, fatigue |

| Tranexamic Acid | Reduce re‑bleeding risk before aneurysm securement | 1g IV over 10min, then 1g infusion over 8h | Thromboembolic events, nausea |

| Acetaminophen | Pain control without affecting platelet function | 1g PO/IV q6h (max 4g/24h) | Liver toxicity at high doses |

Nimodipine: The Cornerstone Drug

Nimodipine is a lipophilic dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker that preferentially dilates small‑ calibre cerebral arteries. Its neuroprotective effect is thought to stem from improved microcirculation rather than systemic blood pressure reduction.

Guidelines from the American Heart Association (2023 update) recommend starting nimodipine within 24hours of bleed, regardless of surgical status. The 60mg q4h regimen has the strongest evidence base; dose reduction is only warranted if systolic pressure falls below 90mmHg.

**Practical tip:** If oral intake is unreliable, a nasogastric tube can deliver the same dose in a liquid suspension. Monitoring includes hourly blood pressure checks for the first 48hours, then every 4hours while on therapy.

Managing Blood Pressure: Antihypertensives

Elevated systolic pressure (>160mmHg) after SAH raises re‑bleeding risk and worsens vasospasm. However, over‑aggressive lowering can compromise cerebral perfusion, especially in patients with impaired autoregulation.

Labetalol and nicardipine are the most used IV agents because they allow rapid titration. Target is a systolic range of 120‑140mmHg, guided by transcranial Doppler (TCD) velocities and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) measurements.

**Monitoring:** Continuous arterial line read‑outs, with adjustments every 15minutes during initial titration. Watch for reflex bradycardia with labetalol and for tachyphylaxis with nicardipine.

Seizure Prophylaxis: Antiepileptic Drugs

Seizures occur in up to 10% of SAH patients, most commonly within the first week. Prophylactic antiepileptic therapy is standard for Hunt‑Hess grades III-V or when cortical irritation is evident on CT.

Levetiracetam is preferred over phenytoin because it has fewer drug‑interaction concerns and a rapid IV formulation. Load with 500mg, then maintain 500mg q12h. Adjust for renal impairment (eGFR<30ml/min/1.73m²) to 250mg q12h.

**Side‑effect watch:** Mood changes and fatigue are common; inform patients and families early to avoid misinterpretation as neurological decline.

Preventing Re‑Bleeding: Antifibrinolytics

Tranexamic acid (TXA) shortens the time to aneurysm securement by limiting clot breakdown. Studies (e.g., ULTRA‑SAH 2022) show a modest reduction in early re‑bleeding without increasing thrombotic complications when used for <24hours.

Administration starts as soon as SAH is confirmed, right before transport to the cath lab or operating theatre. Discontinue immediately after the aneurysm is clipped or coiled.

**Caution:** In patients with a history of deep‑vein thrombosis, discuss risks with the neurosurgical team before initiating TXA.

Pain and Comfort: Analgesics

Pain from meningeal irritation can be severe and may elevate blood pressure. Acetaminophen is first‑line because it avoids platelet inhibition. If breakthrough pain occurs, low‑dose morphine (2‑4mg IV q2h) can be added, but keep the dose <10mg to avoid respiratory depression and hypotension.

**Drug interaction note:** Avoid NSAIDs in the acute phase unless the patient has a clear indication, as they can worsen platelet dysfunction and increase intracranial bleed risk.

Hydrocephalus Management and CSF‑Targeted Medications

Acute obstructive hydrocephalus occurs in roughly 30% of SAH cases. External ventricular drains (EVD) are placed emergently, but medication can help reduce CSF production and inflammation.

Acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, lowers CSF secretion. Typical dosing is 250mg IV q8h, titrated to a target opening pressure <15cmH₂O. Evidence for routine use is mixed, so it’s reserved for patients who cannot undergo immediate EVD placement.

**Monitoring:** Serum bicarbonate and electrolytes daily; watch for metabolic acidosis.

Putting It All Together: A Sample Medication Timeline

- Hour0‑6: Confirm SAH with CT, start tranexamic acid if aneurysm not yet secured, begin oral/NG nimodipine 60mg q4h.

- Hour6‑24: Insert arterial line, initiate labetalol infusion targeting 120‑140mmHg systolic, start levetiracetam 500mg q12h.

- Day1‑3: Continue nimodipine, adjust antihypertensives based on TCD vasospasm readings, provide acetaminophen q6h for pain.

- Day4‑7: Perform daily TCD; if mean flow velocity >120cm/s, consider adding oral nifedipine 30mg q12h (under neurology guidance).

- Day8‑14: Taper nimodipine to 30mg q6h if no vasospasm, assess need for ongoing antiepileptic therapy based on EEG.

All steps are coordinated by an intensive‑care team that records vitals, drug levels, and imaging findings in a shared electronic chart.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Skipping nimodipine: Some clinicians halt the drug when hypotension appears, but the benefit of vasospasm reduction outweighs a modest blood‑pressure drop. Adjust antihypertensives instead.

- Over‑treating hypertension: Aggressive MAP <65mmHg can precipitate cerebral ischemia. Use bedside CPP calculations to balance risk.

- Neglecting drug interactions: Many SAH patients are on statins or anticoagulants for other conditions. Review the medication list daily; avoid combined CYP3A4 inhibitors with nimodipine.

- Inadequate monitoring of electrolytes: Acetazolamide and tranexamic acid can cause metabolic acidosis and hypernatremia. Daily labs are a must.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long should I stay on nimodipine after a subarachnoid hemorrhage?

Guidelines advise a 21‑day course, starting as soon as the bleed is confirmed. The drug is tapered only if severe hypotension develops or if the treating team confirms no vasospasm on serial imaging.

Can I take over‑the‑counter painkillers while on SAH medication?

Acetaminophen is safe and recommended. NSAIDs like ibuprofen should be avoided in the first two weeks because they can impair platelet function and raise the risk of re‑bleeding.

Do I need to continue antiepileptic drugs after discharge?

If you experienced a seizure or have cortical irritation on imaging, most neurologists suggest a minimum of three months of therapy, followed by a gradual taper under EEG monitoring. If no seizures occur, medication can often be stopped earlier.

What signs indicate vasospasm despite medication?

New neurological deficits (weakness, speech changes), worsening headache, or a sudden rise in transcranial Doppler velocities (>200cm/s) suggest vasospasm. Prompt CT‑angiography and possible rescue therapy (e.g., intra‑arterial papaverine) are then considered.

Is it safe to travel by car after being on SAH medication?

Once you’re stable, off the ICU, and your blood pressure is well‑controlled, short car trips are fine. However, avoid driving if you’re still on high‑dose antihypertensives that cause dizziness, or if you’re experiencing side‑effects like drowsiness from antiepileptics.

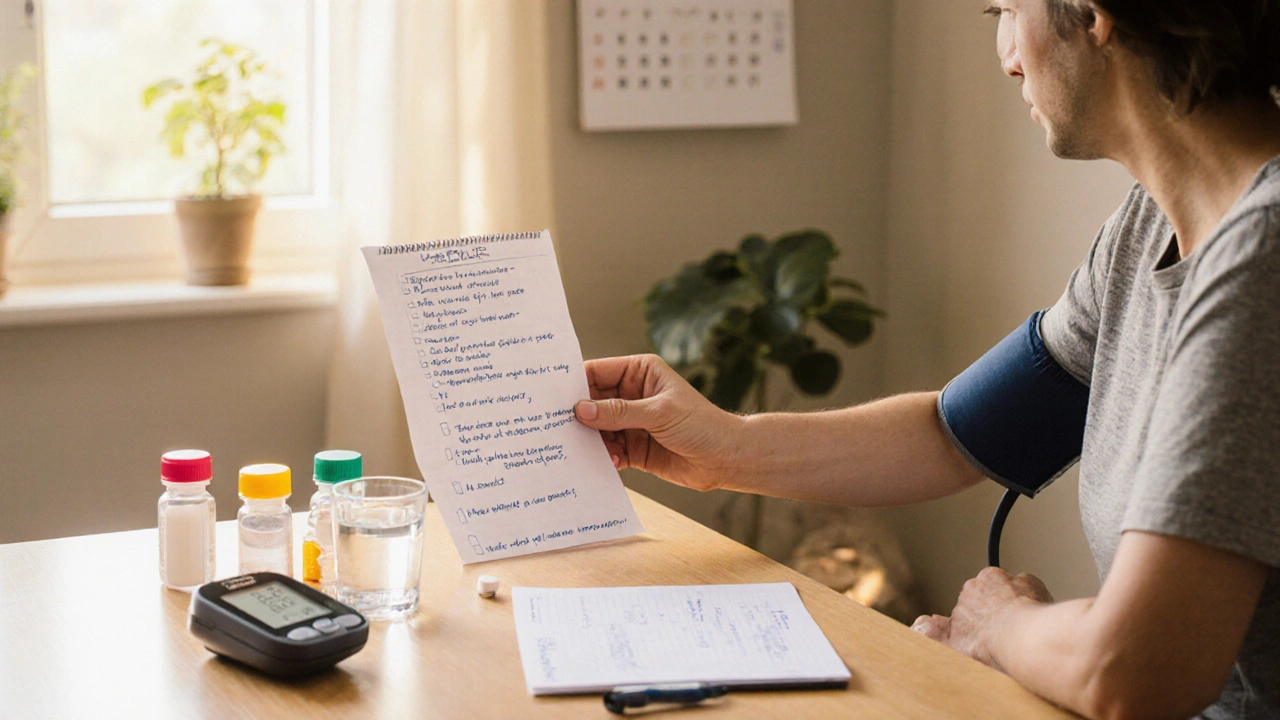

Next Steps for Patients and Caregivers

1. **Create a medication checklist.** Write down each drug, dose, timing, and any special instructions (e.g., take with food).

2. **Schedule daily vitals checks at home** once discharged-blood pressure, heart rate, and any new headaches.

3. **Arrange follow‑up imaging** (usually a CTA at 6weeks) to confirm that the treated aneurysm remains sealed and that no new vasospasm has developed.

4. **Engage a pharmacist** who understands neuro‑critical care. They can spot drug interactions and help adjust doses as kidney function changes.

5. **Join a support group** for SAH survivors. Sharing experiences with medication side‑effects often uncovers practical tips that doctors may not mention.

Medication is a powerful ally in the fight against subarachnoid hemorrhage complications. When paired with vigilant monitoring and a coordinated care team, the right drug regimen can dramatically improve recovery chances and quality of life.

16 Comments

Andrew BuchananOctober 8, 2025 AT 16:50

Thanks for laying out the dosing specifics; I’ll make sure to keep an eye on the blood pressure trends, especially during the first 48 hours of nimodipine therapy.

Krishna ChaitanyaOctober 15, 2025 AT 10:26

Whoa this guide is like a lifesaver in a storm of medical jargon!

diana tutaanOctober 22, 2025 AT 04:02

The article skips over the risks of over‑dosage; you could end up with dangerous hypotension if you’re not vigilant.

Sarah PoshOctober 28, 2025 AT 20:38

Great summary! This will help a lot of junior staff feel more confident when managing SAH patients.

James KnightNovember 4, 2025 AT 14:14

Sure buddy, because nobody actually reads the fine print-just dump the meds and hope for the best, right?

Ajay D.jNovember 11, 2025 AT 07:50

Let’s keep the focus on patient safety; monitoring vitals closely can prevent those hypotension episodes you mentioned.

Dion CampbellNovember 18, 2025 AT 01:26

While the table is aesthetically pleasing, the lack of pharmacokinetic depth reduces its utility for seasoned clinicians.

Burl HendersonNovember 24, 2025 AT 19:02

The omission of half‑life data for agents like labetalol and nimodipine undermines evidence‑based titration protocols, especially when adjusting for cerebral perfusion pressure targets.

Leigh Ann JonesDecember 1, 2025 AT 12:38

The management of subarachnoid hemorrhage is a multifaceted challenge that extends beyond simply securing the aneurysm.

Early initiation of nimodipine has been consistently shown to reduce the incidence of delayed cerebral ischemia.

However, clinicians must balance this benefit against the potential for systemic hypotension, which can compromise cerebral perfusion.

Blood pressure targets should therefore be individualized, aiming for a systolic range of 120 to 140 mmHg while maintaining adequate cerebral perfusion pressure.

Labetalol remains a staple antihypertensive due to its combined alpha and beta blockade, but it requires careful titration to avoid reflex bradycardia.

In patients with reactive airway disease, alternative agents such as nicardipine may be preferable to prevent bronchospasm.

Seizure prophylaxis with levetiracetam is favored over phenytoin because of its more predictable pharmacokinetics and lower interaction profile.

Dose adjustment for renal impairment is essential, as accumulation can lead to increased irritability and fatigue.

Tranexamic acid, when administered before aneurysm occlusion, can reduce the risk of re‑bleeding, yet the clinician should remain alert for thromboembolic complications.

Monitoring for signs of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism is advisable during the infusion period.

Pain control with acetaminophen offers a safe alternative that does not interfere with platelet function, but liver function tests must be checked in patients with pre‑existing hepatic disease.

For patients requiring stronger analgesia, opioids should be used sparingly to avoid respiratory depression and masking of neurologic changes.

Frequent neurological examinations, supplemented by transcranial Doppler studies, provide real‑time feedback on vasospasm development.

When vasospasm is detected, escalation of nimodipine dosage or addition of endovascular therapy may be warranted.

Multidisciplinary communication among neurosurgeons, intensivists, and pharmacists ensures that medication adjustments are made promptly and safely.

Ultimately, adherence to a protocolized medication regimen, combined with vigilant bedside monitoring, is the cornerstone of improving outcomes in SAH patients.

Sarah HoppesDecember 8, 2025 AT 06:14

All that info is just a way for pharma to keep us dependent

Robert BrownDecember 14, 2025 AT 23:50

This whole guide is a waste of time.

Erin SmithDecember 21, 2025 AT 17:26

I think it actually helps a lot of people learn the basics.

George KentDecember 28, 2025 AT 11:02

Patriotic doctors must adopt these protocols!!! They prove our medical excellence!!! No need for foreign guidelines!!!

Jonathan MartensJanuary 4, 2026 AT 04:38

Oh sure because every system works perfectly everywhere

Jessica DaviesJanuary 10, 2026 AT 22:14

The recommendations ignore the potential of newer calcium channel blockers that might outperform nimodipine in certain demographics.

Kyle RhinesJanuary 17, 2026 AT 15:50

There is no solid peer‑reviewed data supporting those newer agents; the studies are funded by vested interests.