Central Cranial Diabetes Insipidus: What You Need to Know Right Now

Ever feel like you’re constantly thirsty and running to the bathroom? If you’re peeing huge volumes of dilute urine and can’t seem to quench your thirst, central cranial diabetes insipidus (CCDI) could be the reason. CCDI happens when the brain stops making enough vasopressin (also called antidiuretic hormone), so your kidneys can’t concentrate urine. That leaves you at risk for dehydration and high sodium if it’s not treated.

Causes and diagnosis

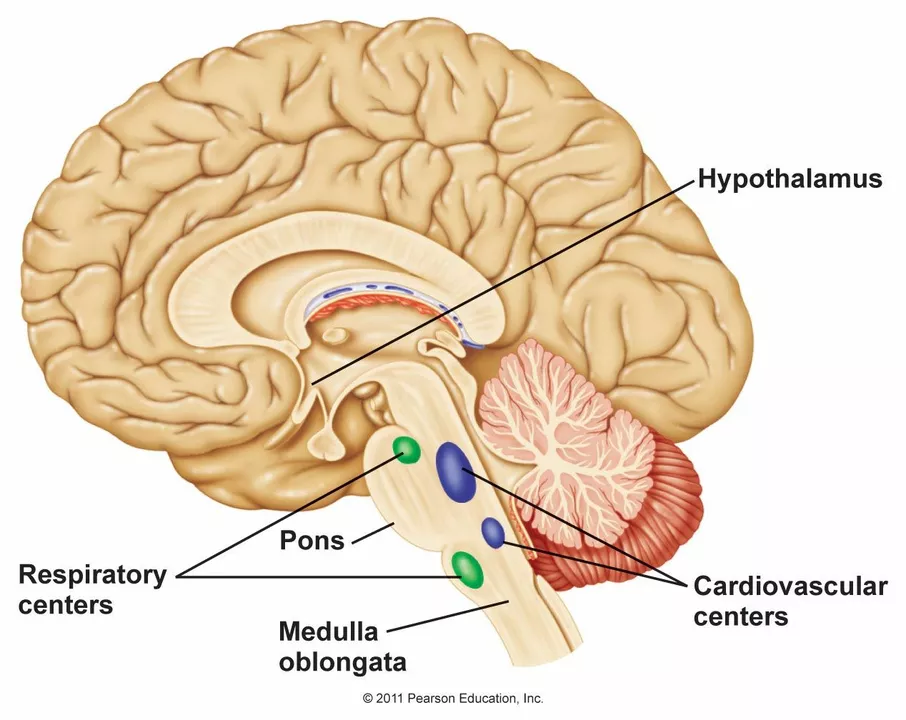

CCDI usually comes from damage to the hypothalamus or posterior pituitary. Common triggers are head trauma, brain surgery, tumors, infections, or autoimmune damage. Sometimes the cause isn’t found and it’s called idiopathic CCDI.

Diagnosing CCDI focuses on a few clear tests: check blood sodium and serum osmolality, measure urine osmolality, and see how much urine you produce in 24 hours. A supervised water deprivation test helps tell CCDI apart from other conditions like primary polydipsia. Doctors often follow with a desmopressin challenge and may order an MRI to look for structural problems in the brain.

Treatment and daily management

Treatment is usually straightforward: replace the missing hormone with desmopressin (DDAVP). It comes as a nasal spray, tablet, or injection. The goal is to stop excessive urine loss while avoiding low sodium from too much water retention. That’s why follow-up blood tests matter—your provider will adjust the dose until urine output and sodium levels are stable.

Everyday tips that help: measure how much you drink and pee, keep a simple log for a week, and learn your usual urine color (pale is normal). Carry a water bottle but avoid overdrinking once treatment is stable. Wear a medical ID if you take desmopressin, since dosing changes may be needed during illness, travel, or after surgery. If you’re pregnant, have heart disease, or are elderly, dosing and monitoring often need extra care.

Watch for red flags: dizziness, confusion, very dry mouth, or very dark urine. Those can mean sodium problems or dehydration and need same-day medical review. Also alert your doctor if you get sick with vomiting/diarrhea or can’t take oral meds—CCDI patients can dehydrate fast.

Long-term outlook is good when CCDI is treated and monitored. Regular check-ins, keeping labs up to date, and knowing when to seek help will cut the risk of complications. If you suspect CCDI, ask your clinician about urine volume records, basic labs, and an MRI—those three steps usually point you in the right direction.

I recently came across some interesting research about the connection between Central Cranial Diabetes Insipidus (CCDI) and brain tumors. It turns out that CCDI, a rare hormonal disorder, can be caused by brain tumors affecting the pituitary gland or hypothalamus. In these cases, the production of the hormone vasopressin is disrupted, leading to excessive urination and thirst. Early diagnosis and treatment of the tumor can help manage CCDI symptoms and improve overall health. This information is crucial for raising awareness and promoting a better understanding of the link between these two conditions.