Antiemetic Selection Guide

How to Use This Tool

Select the type of nausea symptoms and patient factors to determine which antiemetic is most appropriate. Based on evidence from the article, this tool provides recommendations to avoid dangerous combinations and unnecessary medications.

1. What type of nausea is the patient experiencing?

2. Which opioid is the patient taking?

3. Patient age?

4. Any of these comorbidities?

5. Taking these medications?

Recommendation

When someone starts taking opioids for pain, nausea isn’t just an inconvenience-it’s often the reason they stop taking the medication altogether. Studies show that 20 to 33% of patients experience opioid-induced nausea and vomiting (OINV), and many would rather endure more pain than deal with it. That’s not just about discomfort. It’s about treatment failure. If you’re prescribing or taking opioids, understanding how antiemetics work-and when they do more harm than good-isn’t optional. It’s essential.

Why Opioids Make You Nauseous

Opioids don’t just block pain signals. They also mess with your brain’s vomiting center and slow down your gut. The chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), located near the base of your brain, is packed with dopamine receptors. When opioids bind to these, they send false signals that your body is poisoned. That’s why drugs like metoclopramide, which block dopamine, were once the go-to fix. But there’s more. Opioids also activate mu-receptors in your intestines, which slows digestion. That buildup of food and gas triggers nausea. And for some people, especially older adults or those prone to motion sickness, opioids increase sensitivity in the inner ear’s balance system. That’s why dizziness and nausea often come together. The good news? Most people develop tolerance. Within 3 to 7 days of a stable opioid dose, the nausea fades. That’s why blanket prophylaxis-giving antiemetics to everyone-isn’t the answer. It’s about timing, not just medication.Which Antiemetics Actually Work?

Not all antiemetics are created equal. The most common ones used are serotonin blockers, dopamine antagonists, and anticholinergics. But their effectiveness depends on what’s causing the nausea.- Ondansetron (Zofran) and palonosetron (Aloxi) block serotonin in the gut and brain. A 2017 study found palonosetron cut OINV rates to 42%, compared to 62% with ondansetron. That’s a big difference. But both carry a black box warning: they can prolong the QT interval, raising the risk of dangerous heart rhythms, especially in older adults or those on other QT-prolonging drugs.

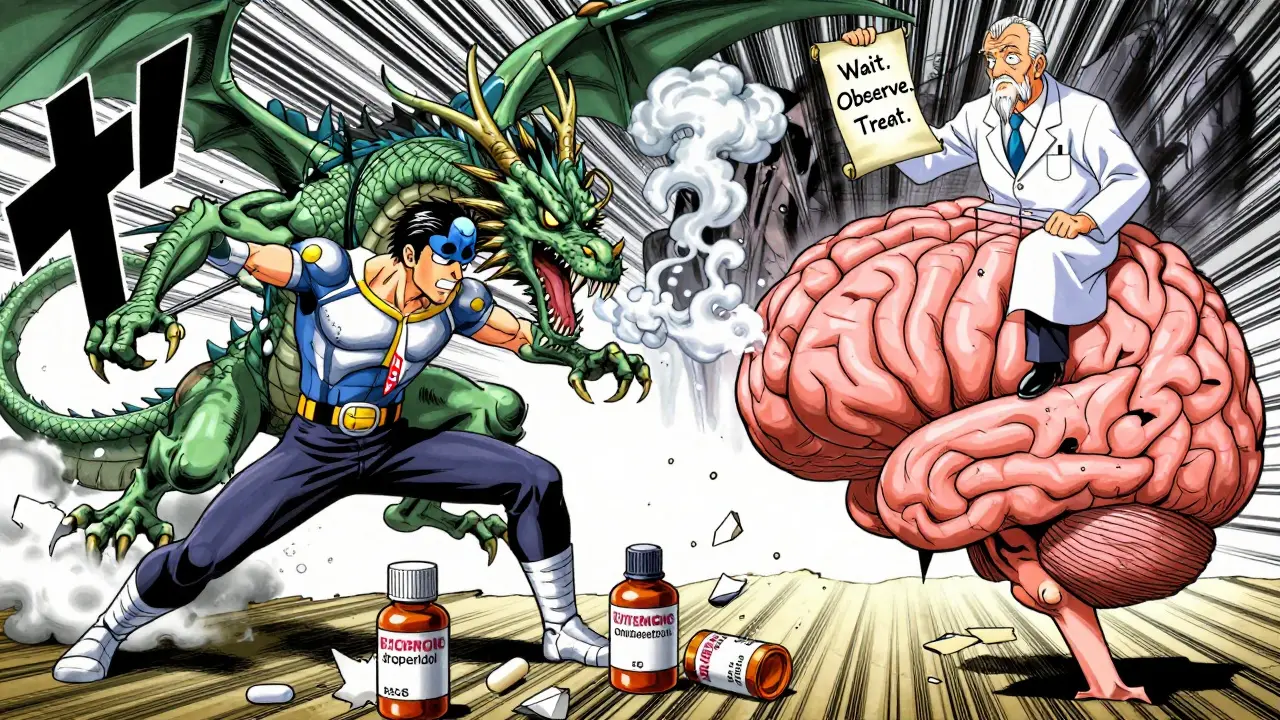

- Metoclopramide (Reglan) is a dopamine blocker and prokinetic. It speeds up stomach emptying and blocks the CTZ. But a 2022 Cochrane review of three small trials found it didn’t reduce nausea or vomiting when given before IV opioids. That’s surprising, given how long it’s been used. The takeaway? Don’t give it preemptively. Save it for when nausea hits.

- Droperidol is another dopamine blocker with a black box warning for cardiac issues. It’s effective but rarely used now because of safety concerns.

- Scopolamine patches and meclizine work best when nausea is tied to dizziness or movement. If the patient feels sick when standing up or walking, these are better choices.

The Big Mistake: Prophylactic Antiemetics

Many clinicians still hand out ondansetron or metoclopramide with the first opioid prescription. It feels proactive. But the evidence says otherwise. The 2022 Cochrane review looked at giving metoclopramide before IV opioids. Three trials, over 300 patients total. Result? No benefit. No reduction in vomiting. No drop in rescue meds. And no increase in side effects. That’s not a win. It’s a waste. Why does this still happen? Tradition. Habit. Fear of patient complaints. But giving drugs “just in case” leads to unnecessary side effects, drug interactions, and higher costs. If a patient doesn’t get nauseous, they didn’t need it. If they do, you can treat it then. The CDC’s 2022 opioid prescribing guideline is clear: educate patients about nausea as a common side effect-but don’t automatically prescribe antiemetics. That’s the standard now.

When Antiemetics Are Dangerous

Opioids and antiemetics aren’t just a pair. They’re a cocktail with hidden risks. The FDA has issued multiple warnings about serotonin syndrome-a life-threatening condition caused by too much serotonin in the brain. It can happen when opioids like tramadol or fentanyl are mixed with SSRIs, SNRIs, or even migraine meds like triptans. Symptoms? Agitation, rapid heart rate, high fever, tremors. It’s rare, but deadly. Also, many antiemetics slow down breathing. That’s a problem when combined with opioids, which already depress respiration. Droperidol, metoclopramide, and even ondansetron in high doses can add to that risk, especially in elderly patients or those with COPD, sleep apnea, or kidney disease. And then there’s the heart. QT prolongation from ondansetron or droperidol can trigger torsades de pointes, a chaotic heart rhythm. The risk is low in healthy young people-but in someone on multiple meds, with electrolyte imbalances or liver problems? It’s not worth the gamble.Best Practices: What to Do Instead

There’s a smarter way. Four evidence-based strategies work better than random antiemetic prescriptions.- Start low, go slow. A morphine dose of 1 mg twice daily for dyspnea in COPD patients often causes minimal nausea. Higher doses? That’s where problems start. Begin with the lowest effective dose and wait days before increasing. Let tolerance build naturally.

- Rotate opioids. Not all opioids cause the same level of nausea. Oxymorphone is notorious. Tapentadol? Much lower risk. If a patient gets sick on oxycodone, switching to hydrocodone or morphine might solve the problem without any antiemetic.

- Adjust the dose. Sometimes, lowering the opioid dose by 25-30% still controls pain but cuts nausea dramatically. That’s not failure. That’s precision.

- Treat, don’t prevent. Wait until nausea appears. Then match the antiemetic to the cause. Is it motion-triggered? Try scopolamine. Is it gut-related? Try a low dose of ondansetron. Is it central? A tiny amount of prochlorperazine might work. Avoid shotgun approaches.

What About Chronic Pain?

Most opioid guidelines now say: avoid long-term use for chronic non-cancer pain. But if it’s necessary-say, for severe arthritis or post-surgical pain that won’t resolve-emphasize non-opioid options first: physical therapy, gabapentin, topical NSAIDs, or nerve blocks. If opioids are still needed, treat nausea as a temporary side effect. Most patients don’t need antiemetics beyond the first week. After that, focus on constipation management-because that’s the real long-term issue.Key Takeaways

- Opioid-induced nausea affects up to one in three patients and is a leading cause of treatment discontinuation.

- Prophylactic antiemetics like metoclopramide don’t work and aren’t recommended.

- Ondansetron and palonosetron are effective for treating established nausea, but carry cardiac risks.

- Always consider opioid rotation before adding an antiemetic-some opioids are simply less nauseating.

- Watch for serotonin syndrome when combining opioids with antidepressants or migraine drugs.

- Tolerance to nausea develops in 3-7 days. Don’t overmedicate.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do all opioids cause nausea equally?

No. Oxymorphone has the highest risk of nausea per dose, followed by oxycodone. Tapentadol and methadone have significantly lower rates. Tramadol is moderate but carries a higher risk of serotonin syndrome. Choosing a less nauseating opioid can eliminate the need for antiemetics entirely.

Can I use ginger or peppermint instead of medication?

Ginger has shown some benefit in postoperative nausea, but there’s no strong evidence it works for opioid-induced nausea. Peppermint tea might soothe the stomach, but it won’t block the brain’s vomiting center. These can be used as supportive measures, but not as replacements for targeted antiemetics when needed.

How long should I give an antiemetic?

For opioid-naïve patients, a short course of 3 to 7 days is usually enough. If nausea persists beyond that, reassess: is the opioid dose too high? Is another drug causing it? Is there an underlying issue like a bowel obstruction? Long-term antiemetic use is rarely needed and increases risk.

Is it safe to give ondansetron with morphine?

Yes, but with caution. Both drugs can slow breathing. Ondansetron can prolong the QT interval, and morphine can lower potassium levels-both increase heart rhythm risks. Monitor for dizziness, palpitations, or fainting. Avoid in elderly patients or those with heart disease. Use the lowest effective dose for the shortest time.

Why isn’t metoclopramide recommended anymore?

Because studies show it doesn’t prevent nausea when given before opioids. It may help if nausea is already happening, especially if the gut is sluggish. But giving it upfront adds cost and risk without benefit. It’s an outdated practice that’s been disproven by modern evidence.

15 Comments

Alexandra EnnsJanuary 24, 2026 AT 13:33

Okay but let’s be real-this whole ‘tolerance in 3-7 days’ thing is a myth pushed by pharma to keep people hooked. I’ve seen patients on oxycodone for 18 months still puking every morning. They’re not ‘tolerating’-they’re being slowly poisoned. And don’t even get me started on how they quietly slip in Zofran like it’s candy. Cardiac arrest doesn’t care if you ‘needed it.’

Marie-Pier D.January 26, 2026 AT 09:10

Thank you for writing this. 💙 I’m a nurse in Ontario and I’ve seen so many patients stop opioids because they thought nausea meant they were ‘doing something wrong.’ You’re right-most just need time. I always tell them: ‘Your body isn’t broken, it’s just learning.’ And if it doesn’t improve? We adjust, we don’t blanket-medicate. ❤️

Dolores RiderJanuary 27, 2026 AT 11:35

They don’t want you to know this… but the FDA knows antiemetics are used to mask opioid side effects so hospitals can hit their ‘pain management satisfaction’ metrics. That’s why they push Zofran like it’s aspirin. Look up the 2021 whistleblower report. They’re making billions off nausea. 😷

Jenna AllisonJanuary 28, 2026 AT 15:23

Important clarification: palonosetron’s 42% OINV rate was in cancer patients on chemo, not opioid-naïve pain patients. The study cited didn’t isolate opioid-induced nausea. That’s a classic misapplication of data. Also, QT prolongation risk is real but mostly with IV use and pre-existing conditions. Oral ondansetron at 4mg? Low risk. Don’t scare people off useful tools.

Sharon BigginsJanuary 29, 2026 AT 13:16

I just started morphine for my back and was terrified of nausea… but I didn’t get any. Not even a little. I just took it slow, ate a cracker before bed, and drank ginger tea. It’s not magic, it’s just… patience. You guys make it sound like a war zone, but sometimes it’s just quiet. 🙏

John McGuirkJanuary 30, 2026 AT 18:07

Let me guess-this was written by a pharma rep pretending to be a clinician. They always say ‘tolerance develops’ so you don’t notice the cognitive decline, the constipation, the emotional numbness. And now they’re pushing ‘rotate opioids’ like it’s a Netflix playlist. Wake up. Opioids are a trap. Always have been.

Michael CamilleriFebruary 1, 2026 AT 09:44

People treat nausea like a bug to be exterminated but it’s a signal. Your body is telling you the drug is too strong. You don’t silence the alarm-you ask why it’s going off. We’ve forgotten how to listen. We medicate discomfort instead of questioning the source. That’s not medicine. That’s spiritual bypassing with a prescription pad.

Darren LinksFebruary 1, 2026 AT 15:09

Oh so now it’s ‘don’t give antiemetics’? What’s next? ‘Don’t give insulin to diabetics until they start vomiting’? This is why America’s healthcare is a dumpster fire. You wait until someone’s in the ER choking on their own bile before you do anything? Brilliant. 🙄

Husain AttherFebruary 2, 2026 AT 01:37

This is one of the most balanced and clinically sound summaries I’ve read on this topic. Thank you for emphasizing individualized care over protocol-driven prescribing. In India, we often see patients on multiple antiemetics out of habit, not evidence. Your four strategies are exactly what primary care needs-simple, safe, and smart.

Helen LeiteFebruary 2, 2026 AT 08:23

OMG I KNEW IT 😱 They’re hiding the truth!! Ondansetron is actually a mind control drug disguised as nausea relief!! I read on a forum that Big Pharma adds microchips to it to track patients!! And the QT prolongation? That’s just the side effect of the signal being sent to your phone!! 📱👁️🗨️

Marlon MentolarocFebruary 3, 2026 AT 04:20

Man, I used to give metoclopramide like it was water until I had a guy code on my floor after a combo of Reglan + morphine + furosemide. His potassium was 2.8. He was 72. We saved him, but I haven’t given it since. Learned the hard way. Always check electrolytes. Always.

Gina BeardFebruary 4, 2026 AT 08:01

Tolerance isn’t magic. It’s neuroadaptation. Stop treating it like a checkbox.

Phil MaxwellFebruary 5, 2026 AT 07:20

I’ve been on hydrocodone for 3 years now. Nausea lasted 4 days. Didn’t need anything. I just ate small meals, stayed hydrated, and didn’t stress about it. Honestly? The post made me feel better about not needing meds for everything. Sometimes the body just needs space.

Shelby MarcelFebruary 6, 2026 AT 20:56

wait so ginger doesnt work? i thought it did?? i mean i read somethign on reddit like 2 years ago and i thought it was legit??

Luke DavidsonFebruary 7, 2026 AT 23:18

Man, this hit different. I’ve been on oxymorphone for my degenerative spine and honestly? I thought I was just weak for getting sick. But reading this… I realized it’s not me. It’s the drug. I switched to tapentadol last month and my nausea? Gone. No pills. No panic. Just… quiet. I wish I’d known this sooner. You don’t have to suffer to be strong. Sometimes strength is knowing when to change course. 🙏