It’s a cruel twist: you’re taking opioids to ease your pain, but the pain gets worse. Not because your injury is getting worse, not because the medication stopped working - but because the medicine itself is making you more sensitive to pain. This isn’t rare. It’s called opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH), and it’s quietly affecting 2 to 15% of people on long-term opioid therapy. Most doctors don’t catch it. And when they don’t, they do the only thing that seems logical - they increase the dose. That makes the pain even worse.

What Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Really Feels Like

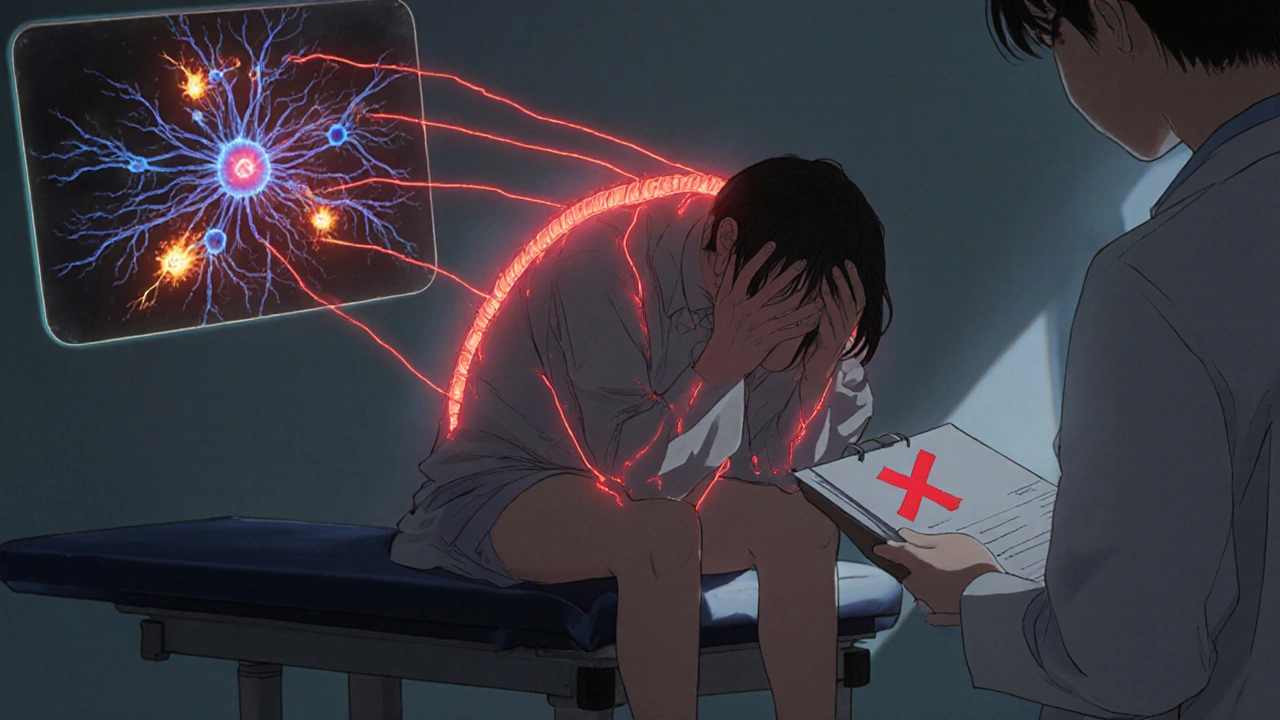

OIH doesn’t look like typical pain. It doesn’t stay where it started. If you had lower back pain from a herniated disc, and now your legs, hips, and even your arms hurt without any new injury, that’s a red flag. If touching your skin - like the pressure of clothing or a light brush - causes sharp pain where it never did before, you’re likely experiencing allodynia, a hallmark of OIH.

Unlike tolerance - where you need more medication to get the same relief - OIH means the more opioid you take, the more pain you feel. Patients often report: "I took my usual dose, and it didn’t help. So I took more. And then I hurt worse than before." This isn’t addiction. It’s a neurological glitch. Your nervous system has been rewired by the drugs meant to calm it.

Research from the Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin (2024) shows OIH typically shows up after 2 to 8 weeks of continuous opioid use. It’s more common with high doses - especially over 300mg of morphine daily - and in people with kidney problems, where opioid metabolites build up. Hydromorphone and intravenous morphine carry the highest risk.

Why Your Body Turns Against the Drug

Opioids don’t just block pain signals. They trigger a cascade of changes in your spinal cord and brain. The most well-understood mechanism involves the NMDA receptor - a key player in pain signaling. When opioids bind to certain brain cells, they accidentally turn on NMDA receptors, which amplify pain instead of suppressing it. Think of it like turning up the volume on a speaker that’s already blaring.

Other pathways include:

- Spinal dynorphin release: A natural pain chemical that, in excess, becomes a pain promoter.

- Descending facilitation: Brain signals that normally dial down pain start screaming it louder.

- Toxic metabolites: Morphine breaks down into morphine-3-glucuronide, a substance that irritates nerve cells.

- Genetic factors: People with certain COMT gene variants are far more likely to develop OIH. These genes control how your body handles stress chemicals like adrenaline and dopamine.

These aren’t theoretical. They’re proven in animal studies and human trials. That’s why ketamine - an NMDA blocker - works so well in reversing OIH. It doesn’t just mask pain. It resets the system.

How Doctors Miss It - and Why It’s So Hard to Diagnose

OIH is a diagnosis of exclusion. That means you have to rule out everything else first: new injuries, infections, nerve damage, cancer progression, or even withdrawal. Many patients are misdiagnosed with "tolerance" and given higher doses - sometimes for months or years.

There’s no single blood test or scan for OIH. But there are clues:

- Pain spreads beyond the original area

- Pain gets worse when opioid dose increases

- Allodynia appears without new trauma

- No improvement despite escalating doses

- Unexplained anxiety, restlessness, or insomnia alongside pain

A 2017 study in the Journal of Pain Research validated the Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Questionnaire (OIHQ), a simple 10-item tool with 85% accuracy in spotting OIH. It asks about pain patterns, medication response, and sensitivity changes. Most clinics don’t use it - but they should.

Quantitative sensory testing (QST) can also help. It measures how much pressure, heat, or cold it takes to trigger pain. In OIH patients, thresholds drop - meaning less stimulus causes more pain. This isn’t routine, but it’s powerful when available.

What Actually Works to Fix It

There’s only one rule: don’t give more opioids. That’s the biggest mistake. Treatment is about stepping back, not pushing forward.

1. Reduce the dose - Slowly. Cut by 10% to 25% every 2 to 3 days. This isn’t withdrawal. You’ll feel better within days, even if the pain doesn’t vanish overnight. Many patients report their pain dropping by 30-50% after just one reduction.

2. Switch opioids - Not all opioids are equal. Methadone is often the best choice because it blocks NMDA receptors like ketamine does. Buprenorphine is another good option - it has a ceiling effect and doesn’t trigger the same neurochemical chaos. Avoid switching to another high-dose morphine or hydromorphone product.

3. Add ketamine - Low-dose IV ketamine (0.1-0.5 mg/kg/hour) can reverse OIH in as little as 24-48 hours. Oral or nasal ketamine is less studied but shows promise. It’s not a cure-all, but for severe cases, it’s life-changing.

4. Use gabapentin or pregabalin - These drugs calm overactive nerves. Doses of 300-1800 mg three times daily help reduce central sensitization. Clonidine (0.1-0.3 mg twice daily) also helps by reducing sympathetic overdrive.

5. Add non-drug therapies - Physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) help retrain the brain’s pain response. In one 2022 trial, patients using CBT alongside opioid tapering saw 40% greater pain reduction than those on medication alone.

What Doesn’t Work - and Why

Increasing the opioid dose? That’s the trap. It makes OIH worse. Adding another painkiller like NSAIDs or acetaminophen won’t fix the neurological rewiring. Benzodiazepines might calm anxiety but don’t touch the core problem. And don’t assume it’s "just in your head." OIH is real, measurable, and biological.

Some experts - like Dr. Perry Fine - argue OIH is overdiagnosed because most evidence comes from lab studies using experimental pain, not real-world chronic pain. But that’s like saying heart attacks are rare because most studies use healthy volunteers. Real patients are suffering. And when you treat them right, they get better.

What’s Changing in 2025

Things are shifting. In 2022, the FDA required opioid labels to include warnings about OIH. Pain fellowships now teach it - 78% of programs cover it, up from 35% in 2015. The American Academy of Pain Medicine reports that 65% of specialists now screen for OIH - up from 30% in 2010.

Genetic testing is coming. Two commercial panels, expected to launch in Q2 2025, will test for COMT variants linked to OIH risk. Imagine knowing before you start opioids whether you’re genetically prone to this side effect. That’s not science fiction - it’s next year.

The NIH is funding a major study (NCT05217891) to find biomarkers for OIH susceptibility. And pharmaceutical companies are pouring money into new NMDA modulators - three are now in Phase II/III trials.

What to Do If You Suspect OIH

If you’re on long-term opioids and your pain is getting worse:

- Write down your pain patterns - where it hurts, when it gets worse, what makes it better or worse.

- Track your opioid doses and how you feel after each change.

- Ask your doctor: "Could this be opioid-induced hyperalgesia?" Show them the OIHQ if you can find it online.

- Request a referral to a pain specialist who understands OIH - not just addiction specialists.

- Don’t stop opioids cold turkey. Work with your team to taper safely.

It’s not weakness to ask for help. It’s the smartest thing you can do.

Final Thoughts

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia isn’t a myth. It’s not rare. And it’s not your fault. It’s a biological side effect of a powerful class of drugs - one we’ve misunderstood for decades. The good news? Once you recognize it, you can fix it. You don’t need more pills. You need less - and smarter ones.

For the 10.1 million Americans still on long-term opioids - and the millions more worldwide - understanding OIH could mean the difference between lifelong suffering and real relief. It’s time we stopped treating pain with more pain.

Is opioid-induced hyperalgesia the same as tolerance?

No. Tolerance means you need higher doses to get the same pain relief. OIH means your pain gets worse when you take more opioids. You can have both at the same time, but they require different treatments. Tolerance is managed by dose increases - OIH is managed by dose reduction.

Can OIH happen with low-dose opioids?

Yes. While it’s more common with high doses - especially over 300mg of morphine daily - OIH can occur at lower doses, particularly in people with kidney problems or genetic risk factors. Duration matters too: even low doses over several months can trigger it.

How long does it take to recover from OIH?

Most people see improvement within 2 to 4 weeks of reducing their opioid dose. Full recovery can take 4 to 8 weeks. Some patients report lingering sensitivity for months, especially if OIH went untreated for a long time. Adding ketamine or gabapentin can speed up recovery.

Is ketamine safe for treating OIH?

At low, controlled doses (0.1-0.5 mg/kg/hour IV), ketamine is safe and effective for reversing OIH. Side effects like dizziness or dissociation are usually mild and short-lived. It’s not addictive at these doses. Oral and nasal forms are being studied, but IV remains the gold standard for rapid relief.

Will stopping opioids make my pain worse?

Initially, yes - but not because of withdrawal. It’s because your nervous system has been overstimulated. As the opioids clear and your system resets, pain often improves significantly. Many patients report less pain after tapering than they had before starting opioids. A slow, guided taper with supportive meds like gabapentin makes this manageable.

Can genetic testing predict if I’ll get OIH?

Not yet in routine practice - but it’s coming. Two commercial genetic tests targeting COMT variants linked to OIH risk are expected to launch in Q2 2025. These could help doctors choose safer pain treatments before starting opioids, especially for high-risk patients.

9 Comments

Kevin WagnerNovember 13, 2025 AT 18:03

This is the most real thing I’ve read all year. I was on 400mg morphine for three years after a car wreck, and my pain went from a 6 to a 9-then my doc doubled my dose. I thought I was broken. Turns out my nerves were screaming. I tapered with buprenorphine and ketamine infusions. Six months later? I’m hiking again. No pills. No guilt. Just me and my damn legs working again.

gent woodNovember 14, 2025 AT 01:33

Finally, someone articulates what so many of us have endured silently. The misdiagnosis as 'tolerance' is criminal. I've seen patients driven to desperation because their pain escalated with every pill. The OIHQ is underused-why? Because it requires time, and time costs money. But this isn't just clinical-it's human. We need systemic change, not just individual fixes.

Dilip PatelNovember 15, 2025 AT 10:46

u think this is bad? in india we dont even have access to opioids properly, so how we get this hyperalgesia? u americans always overmedicate. my cousin took tramadol for a week and now he cant walk. but he still asked for more. dumbass. this is why your healthcare is broken. no discipline. no willpower. just pills pills pills.

Jane JohnsonNovember 15, 2025 AT 22:27

It's worth noting that the majority of OIH cases occur in patients who were never properly evaluated for psychiatric comorbidities. Anxiety, depression, and somatization often masquerade as hyperalgesia. The article ignores this entirely. A cautious, evidence-based approach requires ruling out psychological contributors before attributing pain escalation to neuroplastic changes.

Peter AultmanNovember 17, 2025 AT 12:09

Been there. Did the taper. Took 3 weeks but the difference was night and day. My skin stopped feeling like it was on fire. My doctor didn’t even know about OIH until I showed him this article. Now he’s asking for copies. Seriously, if you’re on long-term opioids and things are getting worse-don’t panic. Don’t quit cold. Just talk to someone who gets it. It’s fixable.

Sean HwangNovember 17, 2025 AT 17:34

low dose opioids can still do this. my buddy was on 15mg oxycodone a day for 8 months after back surgery. started feeling pain in his hands and feet. doc said he was being dramatic. he got off it slow, added gabapentin, and now he’s back to gardening. no big drama. just smart choices.

Barry SandersNovember 18, 2025 AT 19:38

So let me get this straight-your body rebels against painkillers, so you stop taking them? Shocking. Next you’ll tell us breathing air can cause oxygen toxicity. This is just a fancy way to say ‘I’m addicted and don’t want to admit it.’

Chris AshleyNovember 19, 2025 AT 20:58

bro i just started taking oxys for my sciatica and my leg feels like it’s on fire now?? is this it?? should i stop??

Kevin WagnerNovember 20, 2025 AT 15:23

Don’t stop. Not yet. But don’t take more either. Talk to your doc tomorrow. Ask if they’ve heard of OIH. Print this article. Bring it. You’re not crazy. You’re not weak. You’re just one step away from getting your life back. I was you. You’re gonna be okay.