Warfarin Dosing Calculator

How Warfarin Works

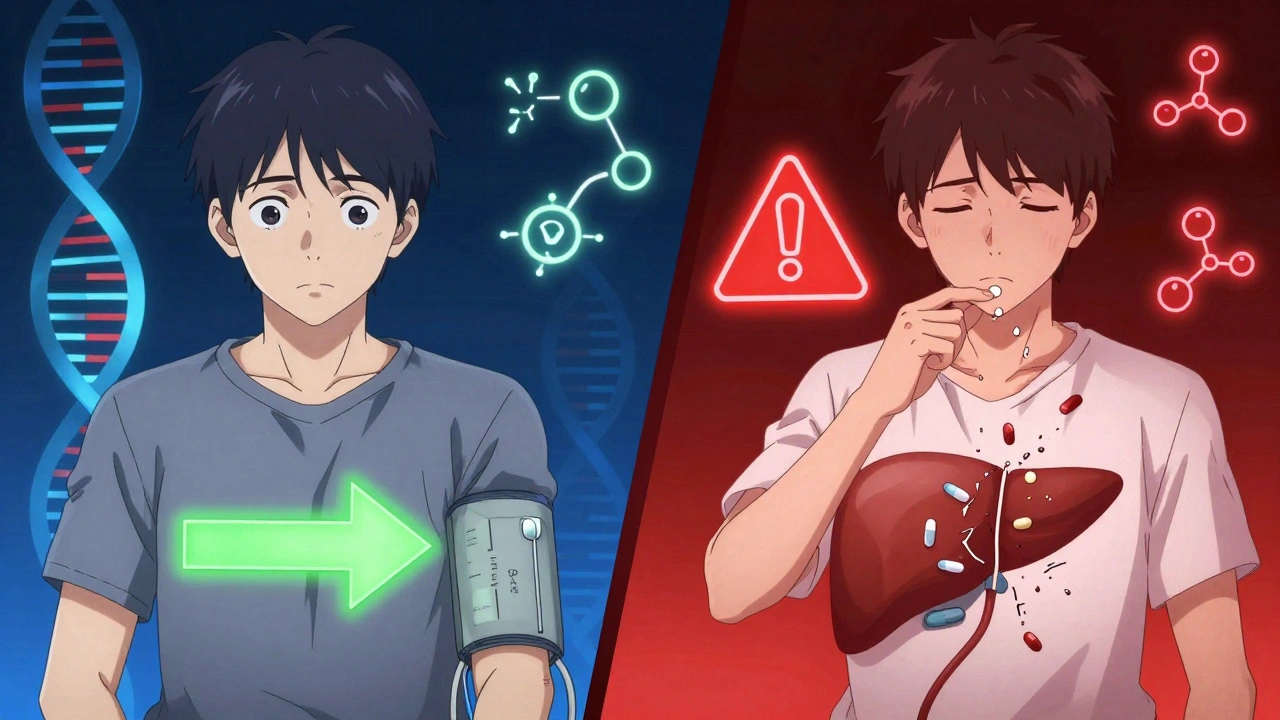

Warfarin dosage varies significantly by genetics and ethnicity. Your body's CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genes affect how you process this blood thinner. This calculator provides general guidance based on scientific research, but your doctor must determine your final dose.

Recommended Dose

Enter your information to see your estimated daily dose

When you take a pill, your body doesn’t treat it the same way everyone else does. Two people with the same diagnosis, same dose, same symptoms - one feels better quickly, the other doesn’t respond at all, or worse, ends up in the hospital from a side effect. This isn’t random. It’s often rooted in genetics, and those genetic patterns often cluster along ethnic lines. The truth is, ethnicity isn’t just a social label - it can be a rough map to how your body handles medicine.

Why Some Drugs Work Better for Certain Groups

Take blood pressure medication. For decades, doctors noticed that African American patients often didn’t respond well to ACE inhibitors, a common class of drugs. Studies showed they were 30% to 50% less likely to see their blood pressure drop compared to white patients. That wasn’t because they weren’t taking the pills - it was because their bodies processed them differently. In 2005, the FDA approved a combination drug called isosorbide dinitrate/hydralazine specifically for self-identified African American patients with heart failure. It wasn’t because race itself caused the difference - it was because certain genetic variants common in people with recent African ancestry affect how the body responds to these drugs. The same pattern shows up with warfarin, a blood thinner. European Americans typically need lower doses than African Americans. Why? Because two genes - CYP2C9 and VKORC1 - control how warfarin is broken down and how sensitive the body is to it. Variants of these genes are more common in African populations, meaning they clear the drug faster and need higher doses to get the same effect. If you guess the dose based on weight or age alone, you’re setting someone up for a clot or a bleed.The Enzymes That Decide Your Drug Fate

Your liver has a team of enzymes that act like molecular scissors, cutting drugs into pieces so your body can use or get rid of them. The most important ones belong to the cytochrome P450 family - especially CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4. These enzymes handle about 70% of all prescription drugs, from antidepressants to statins to painkillers. Here’s where things get personal. A genetic variation called CYP2C19*2, which makes the enzyme less effective, shows up in 15% to 20% of East Asians. That’s a problem for people taking clopidogrel (Plavix), a drug used after heart attacks to prevent clots. If you’re a poor metabolizer, the drug doesn’t activate properly - and your risk of another heart attack goes up. In contrast, only 2% to 5% of African Americans carry this variant. So a doctor prescribing Plavix to a patient from China might be thinking about a different genetic risk than one prescribing it to a patient from Nigeria. Then there’s CYP2D6. Some people have extra copies of this gene - they’re called ultrarapid metabolizers. That means they turn codeine into morphine way too fast. In Northern Europeans, about 1% to 2% have this trait. In parts of East Africa, it’s as high as 29%. A child given codeine for pain after surgery could end up with a dangerous morphine overdose - not because the doctor gave too much, but because their genes turned it into something far stronger than intended.When Genetics Can Be Deadly

Some drug reactions aren’t just ineffective - they’re life-threatening. Carbamazepine, used for epilepsy and bipolar disorder, can cause a severe skin reaction called Stevens-Johnson syndrome. For most people, it’s rare. But for people with the HLA-B*15:02 gene variant, the risk jumps 1,000-fold. That variant is common in Han Chinese, Thai, and Malaysian populations - present in 10% to 15% of people. It’s nearly absent in Europeans, Africans, and Japanese. Because of this, countries like Taiwan and Thailand now require genetic testing before prescribing carbamazepine. The FDA recommends it too. But here’s the catch: even in those populations, not everyone with the gene has a reaction - and some without it still do. That’s why testing isn’t just about ethnicity - it’s about the actual gene. Another example is G6PD deficiency. This inherited condition affects 10% to 14% of African American men and up to 30% of people in malaria-prone areas. If someone with G6PD deficiency takes primaquine (used to treat malaria) or certain antibiotics like dapsone, their red blood cells can break apart suddenly, causing anemia, jaundice, and kidney failure. Screening for this isn’t routine in the U.S., but in places like Nigeria or India, it’s standard before giving these drugs.

Why Race Isn’t Enough - And What Replaces It

Using race as a shortcut for genetics is risky. It’s like using a country’s flag to guess someone’s favorite food. One person might be Nigerian, another Jamaican - both labeled “Black” - but their genetic backgrounds are more different than either is from a Swede. Dr. Sarah Tishkoff’s research showed that two African populations can be more genetically distinct than an African and a European. So if you assume all African descent people respond the same to a drug, you’ll mislead some and harm others. The real goal isn’t to treat people by their ethnicity - it’s to treat them by their genes. That’s where pharmacogenomics comes in. It’s the science of matching drugs to your DNA. The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) has issued 27 guidelines for how to adjust dosing based on genetic test results - for drugs like statins, antidepressants, blood thinners, and pain meds. And it’s working. At Vanderbilt and Mayo Clinic, patients enrolled in pharmacogenomic programs saw 28% to 35% fewer serious side effects. The problem? Testing isn’t widely available. Only 37% of U.S. hospitals offer full pharmacogenetic testing. And it costs $1,200 to $2,500 - out of reach for most. Insurance rarely covers it unless you’ve already had a bad reaction. Meanwhile, the FDA now requires drug companies to collect genetic data in clinical trials. In 2022, 78% of new drug applications included this data - up from 42% in 2015. That’s progress.The Future: Beyond Single Genes

The next wave isn’t just testing one gene at a time. It’s polygenic risk scores - looking at hundreds or even thousands of genetic markers together to predict how you’ll respond to a drug. Early studies show these scores are 40% to 60% more accurate than using race or a single gene. Imagine a test that doesn’t just say “you’re a slow metabolizer of CYP2C19” but says “your overall genetic profile suggests you need 25% less of this antidepressant and are at higher risk for weight gain.” That’s the future. Projects like NIH’s All of Us program are building the most diverse genomic database ever - with 80% of its 3.5 million participants from racial and ethnic minorities. That’s critical. Right now, 81% of all genetic studies are based on people of European descent. We’re missing huge chunks of human diversity. Without that, our predictions will keep failing for non-white populations.

10 Comments

Haley P LawDecember 8, 2025 AT 12:10

So basically we’re just replacing one stereotype with another? 😒 Genetics? Sure. But you’re still using skin color as a proxy for DNA. That’s not science - that’s lazy math.

Chris MarelDecember 8, 2025 AT 19:30

I’m from Nigeria and my uncle died on warfarin because they gave him a standard dose. No one asked about his ancestry. Just assumed he was ‘Black’ and moved on. This isn’t theoretical - it’s personal.

Kathy HaverlyDecember 10, 2025 AT 05:41

Oh please. You’re telling me that a Nigerian and a Jamaican have the same genes because they’re both ‘Black’? Wake up. That’s like saying all Asians are good at math because one guy aced calculus. This whole post is just institutional racism with a lab coat.

ian septianDecember 11, 2025 AT 01:56

Ask for genetic testing. It’s not hard. It saves lives.

Evelyn PastranaDecember 12, 2025 AT 16:16

My grandma took Plavix for years. Never had a clot. But her doctor never tested her genes. Guess what? She’s half Filipino. So yeah, I’m gonna roll my eyes at the ‘one size fits all’ nonsense. 🙄

Nikhil PattniDecember 12, 2025 AT 23:58

Look, I’m from India and we’ve been screening for G6PD deficiency since the 80s because malaria meds kill people if you don’t - it’s basic public health. But in the U.S., you wait for someone to bleed out before you even think about genetics? That’s not just negligent, it’s criminal. And don’t get me started on how insurance refuses to cover tests until after you’re in the ICU. Meanwhile, in Germany, they do preemptive panels for everyone on SSRIs. Why? Because they care about outcomes, not profits. Here? You’re a data point until you’re a lawsuit.

Sabrina ThurnDecember 13, 2025 AT 23:55

The CPIC guidelines are underutilized because most clinicians lack training in pharmacogenomics - not because the science is flawed. We need mandatory modules in residency programs, not just another whitepaper. The data exists. The tools exist. The will? Still catching up. And until we stop conflating ancestry with race, we’ll keep misprescribing - even with perfect genotyping.

George TaylorDecember 15, 2025 AT 07:07

...And yet, the FDA still allows race-based labeling in 12% of drug indications... so much for ‘progress’... (sigh)... it’s always something... you know?... it’s just... frustrating... because we *know* better... but we don’t... do... anything... about it...

Andrea DeWinterDecember 16, 2025 AT 11:13

Hey everyone - I’m a clinical pharmacist and I’ve been pushing for genetic testing in my clinic for years. We started with clopidogrel and warfarin. Within 6 months, ER visits for bleeding dropped by 40%. It’s not magic. It’s biology. And if your doctor hasn’t heard of CYP2C19 or HLA-B*15:02, ask them to look it up. Or better yet - get your own saliva test from 23andMe or Color. It’s $99. You might save your life. Seriously. I’ve seen it happen. Don’t wait for a tragedy to ask for answers.

Elliot BarrettDecember 18, 2025 AT 01:00

This whole thing is just a distraction. If you’re poor, you can’t afford the test anyway. If you’re Black or brown, your doctor won’t even order it. So stop pretending this is about science - it’s about who gets cared for. The rest is just noise.