Spina Bifida: What You Need to Know Now

Spina bifida is a neural tube defect where the spine doesn’t close fully before birth. It can show up as a tiny skin dimple or as a major spinal opening with nerves exposed. You might be surprised to learn it ranges from mild and unnoticed to life-changing. If you or someone you care for faces this diagnosis, the useful facts below will help you ask the right questions and find real support.

How spina bifida happens and how to prevent it

The neural tube forms very early in pregnancy, often before a woman knows she’s pregnant. Low folate (vitamin B9) around conception is the single most preventable risk factor. Health authorities recommend 400 micrograms (mcg) of folic acid daily for most women starting at least one month before trying to conceive and through the first trimester. If you’ve had a prior pregnancy affected by spina bifida or you take certain epilepsy medicines, doctors often advise a higher dose—typically 4,000 mcg (4 mg)—but that needs a prescriber's guidance.

Other risk factors include uncontrolled diabetes, obesity, and some anti-seizure drugs (for example, valproate). Stopping smoking, stabilizing blood sugar, and discussing medication risks with your provider can cut risk. Prenatal screening—maternal serum AFP and targeted ultrasound—can detect many cases before birth so families can plan care.

Signs, treatment options, and everyday care

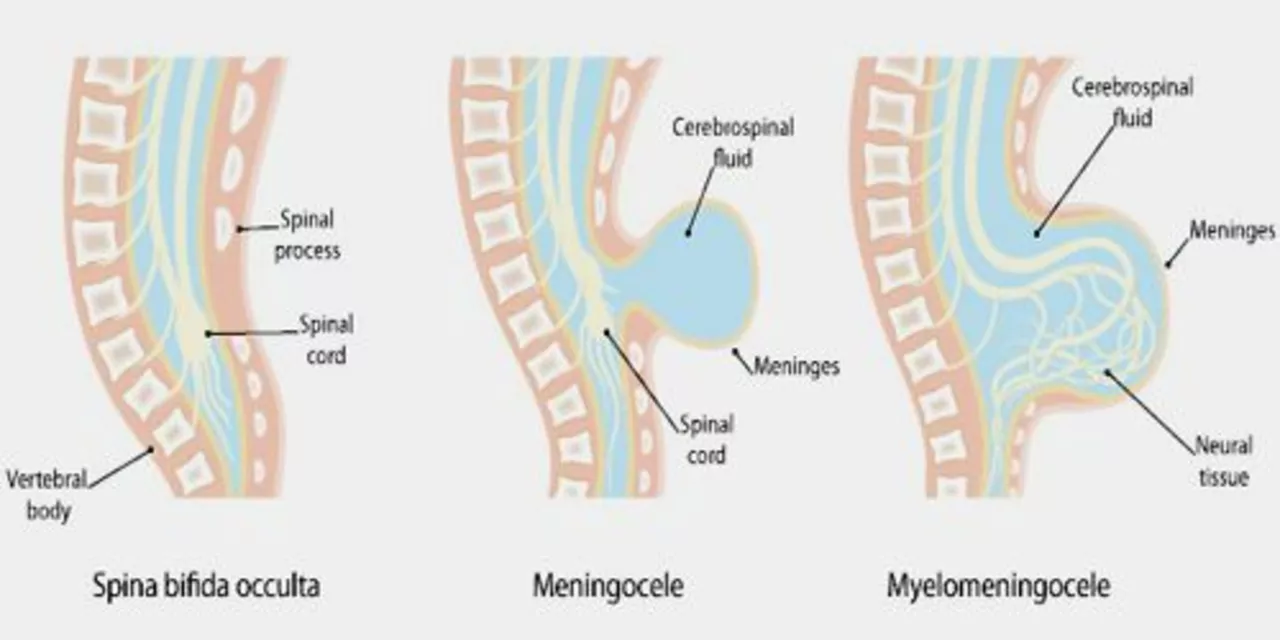

There are three main types: spina bifida occulta (hidden, often harmless), meningocele (membrane bulge), and myelomeningocele (most serious, with nerve impact). Newborns with myelomeningocele often need surgery soon after birth to close the gap and protect the spinal cord. Hydrocephalus (fluid on the brain) is common and may require a shunt to drain excess fluid.

Long-term care is team-based: neurosurgeons, urologists, orthopaedists, physiotherapists, and continence specialists work together. Bladder and bowel management may include timed voiding, medications, or clean intermittent catheterization—simple routines that protect the kidneys and keep daily life predictable. Mobility aids, braces, and early physio help children reach movement goals and improve independence.

Practical tip: set up a care notebook with surgery dates, medications, therapy notes, and contact numbers. That saves hours when visiting clinics. Also look for local support groups and early intervention services—these provide emotional help and ideas from families living this every day.

If you’re planning pregnancy, talk to your GP or midwife about folic acid and any medications you take. If your child has spina bifida, focus on prevention of complications (UTIs, skin breakdown, contractures) and on small daily wins—mobility, social inclusion, school access. Good care is steady, team-based, and focused on quality of life rather than only on the diagnosis.

As a blogger, I've recently come across the significant connection between spina bifida and mental health challenges. It's important to understand that individuals with spina bifida often face various emotional and cognitive difficulties due to the complexity of their condition. In my research, I found that these individuals have a higher risk of developing mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem. This connection highlights the need for comprehensive care that addresses both the physical and mental health aspects of spina bifida. In conclusion, raising awareness and providing proper support is crucial in improving the quality of life for those living with spina bifida and associated mental health challenges.