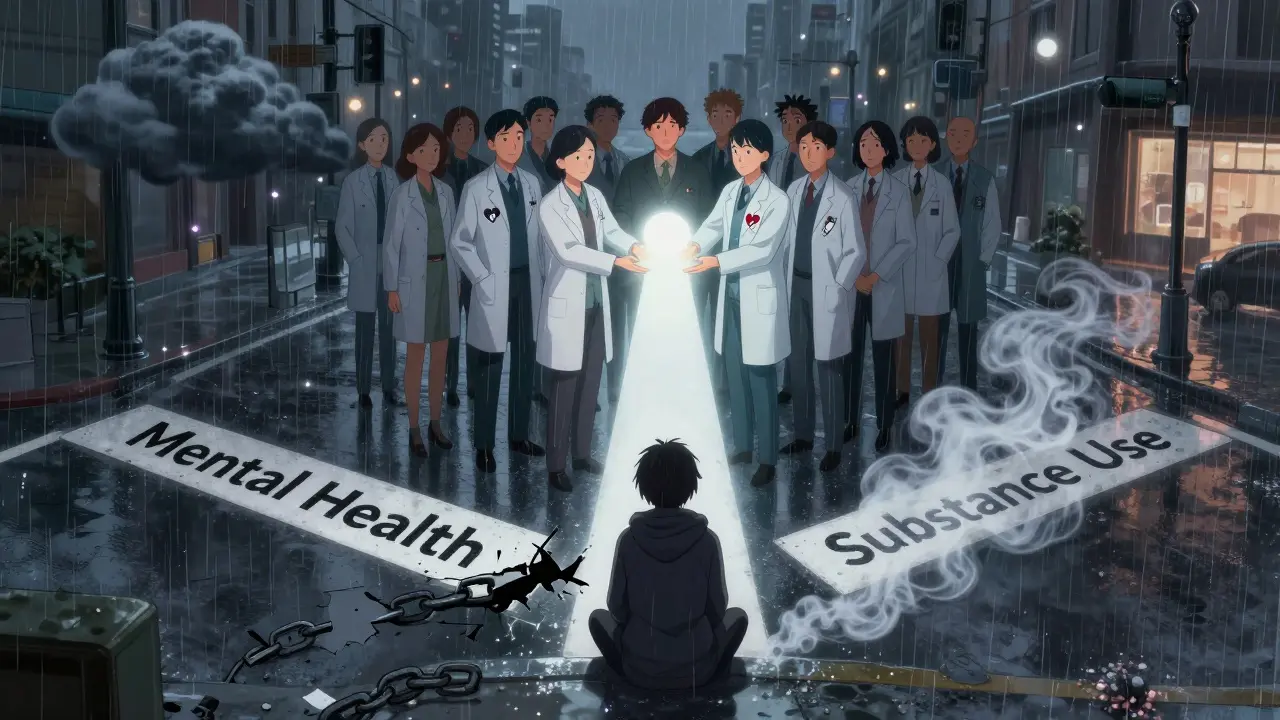

Imagine you’re trying to fix two broken pipes in your house, but you can’t turn off the water to one without flooding the other room. That’s what it’s like for millions of people living with both a mental illness and a substance use disorder. Treating one without the other doesn’t work - and often makes things worse. This is why integrated dual diagnosis care isn’t just a better approach - it’s the only one that truly helps.

Why Separate Treatment Fails

For years, the system treated mental health and substance use as two separate problems. Someone with depression and alcohol dependence would be sent to a therapist for their mood, then to a rehab center for their drinking. But here’s the problem: the two feed each other. Untreated anxiety makes someone more likely to use drugs to cope. Heavy drug use can trigger or worsen psychosis, depression, or bipolar symptoms. When care is split, patients get lost in the shuffle. They hear conflicting messages. One provider tells them to stop drinking; another tells them to take medication that interacts dangerously with alcohol. They’re told to go to two different clinics, on different days, with different staff. No wonder only about 6% of people with co-occurring disorders get the care they need.What Integrated Dual Diagnosis Care Actually Is

Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment, or IDDT, is the gold standard for treating both conditions at the same time - by the same team, in the same place. Developed in the 1990s at Dartmouth and refined by the New Hampshire model, IDDT doesn’t just combine services. It rebuilds them from the ground up. Instead of separate programs, you get one care team trained in both mental illness and addiction. They use one assessment, one treatment plan, and one set of goals. This isn’t theory - it’s backed by decades of research and endorsed by SAMHSA, the CDC, and major medical associations.IDDT is built on nine core components:

- Motivational interviewing - helping people find their own reasons to change, not being told what to do.

- Substance abuse counseling - focused on reducing harm, not just pushing for abstinence.

- Group therapy - where people learn from others who understand both struggles.

- Family psychoeducation - teaching loved ones how to support without enabling.

- Self-help group participation - connecting people to AA, NA, or dual-recovery groups.

- Medication management - carefully balancing psychiatric meds with substance use risks.

- Health promotion - addressing sleep, nutrition, and physical health that often get ignored.

- Secondary interventions - for those who aren’t responding, offering more intensive support.

- Relapse prevention - planning for setbacks before they happen.

How It’s Different: Harm Reduction Over Abstinence

One of the biggest shifts in IDDT is letting go of the idea that everyone must quit cold turkey right away. For many, especially those with severe mental illness, abstinence isn’t realistic - not yet. Instead, IDDT uses harm reduction. If someone is still using, the team works with them to reduce the damage: safer injection practices, avoiding mixing alcohol with antipsychotics, reducing frequency, or switching from opioids to prescription alternatives under supervision. This isn’t giving up - it’s meeting people where they are. Studies show this approach keeps people engaged longer, and eventually, many do reduce or stop use on their own terms.

Real Results: What the Data Shows

A 2018 randomized trial involving 154 patients with severe mental illness and substance use disorders found that after IDDT, participants used alcohol or drugs on significantly fewer days over 12 months. That’s a measurable win. Another study from the Washington State Institute for Public Policy found IDDT reduced alcohol use disorder symptoms by 0.165 and illicit drug use symptoms by 0.207 on standardized scales. That might sound small, but in real life, it means fewer ER visits, fewer arrests, fewer hospitalizations. People start holding jobs again. They reconnect with family. They stop sleeping in shelters.But here’s the catch: not all outcomes improved. The same study found no major change in depression scores, motivation levels, or the therapeutic relationship between patient and provider. Why? Because implementation matters. If the team isn’t trained properly, if they don’t truly understand both disorders, if they’re overworked or underfunded - IDDT falls apart. One study found that even after a three-day training, clinicians didn’t improve their skills in motivational interviewing. That’s not the model’s fault - it’s a failure in support.

The Hidden Crisis: Only 6% Get Help

An estimated 20.4 million U.S. adults had a dual diagnosis in 2023. Yet, only about 6% received integrated care. That leaves over 19 million people stuck in a broken system. Why? Three big reasons:- Funding gaps - Most insurance systems still pay separately for mental health and addiction services. Integrated care costs more upfront, and many providers can’t afford to shift.

- Staff shortages - Few clinicians are trained in both areas. It takes time, money, and ongoing education to build that expertise.

- Fragmented systems - Mental health clinics and addiction centers often operate in different buildings, with different rules, different paperwork. Integrating them requires organizational courage.

States like Washington and New Hampshire have shown it’s possible. With state grants and technical support from SAMHSA, they’ve built teams that work across departments, share records, and use the same protocols. The benefit-cost ratio is still low - about $0.50 saved for every $1 spent - but the real value isn’t in dollars. It’s in lives.

What Recovery Looks Like

A woman with bipolar disorder used to drink heavily to silence her racing thoughts. After years of failed treatments, she joined an IDDT program. Her counselor didn’t judge her for drinking. Instead, they talked about how alcohol made her manic episodes worse. They adjusted her medication. She started attending a dual-recovery group. She learned to recognize her triggers - loneliness, sleep loss, arguments. She didn’t quit drinking overnight. But over six months, she went from daily drinking to once a week, then to none. Her mood stabilized. She got her GED. She started volunteering. She says, “For the first time, I felt like I wasn’t broken - I was being helped.”This isn’t rare. It’s what happens when care is coordinated, compassionate, and consistent.

The Future of Dual Diagnosis Care

The trend is clear: healthcare is moving toward whole-person care. Medicaid and Medicare are starting to reimburse for integrated services. More states are creating Co-Occurring State Infrastructure Grants. But progress is slow. Without more funding for training, better data systems, and policies that pay for integrated care - millions will continue to fall through the cracks.Integrated dual diagnosis care isn’t a luxury. It’s the bare minimum we owe to people who are suffering from two illnesses at once. It’s not about perfection. It’s about showing up - together - for the people who need it most.

What is the difference between parallel and integrated treatment for dual diagnosis?

Parallel treatment means separate providers and programs for mental illness and substance use - like seeing a psychiatrist for depression and a counselor for addiction in different offices. Integrated treatment brings both under one team, using one assessment and one treatment plan. The key difference is coordination: integrated care ensures every decision considers both conditions, while parallel treatment often ignores how one affects the other.

Does integrated dual diagnosis care require abstinence from drugs or alcohol?

No. IDDT uses harm reduction, which means the goal is to reduce the negative consequences of substance use - not necessarily stop immediately. For people with severe mental illness, forcing abstinence too soon can lead to dropout or worsening symptoms. Instead, the team works with the person to reduce use, avoid dangerous combinations, and build stability. Many eventually choose abstinence, but only when they’re ready.

How long does integrated dual diagnosis treatment usually last?

There’s no fixed timeline. Treatment is ongoing and tailored to the individual. Most programs start with intensive support (daily or weekly sessions) and gradually reduce frequency over months or years. Recovery is not linear, so ongoing check-ins, relapse prevention planning, and access to support groups are part of long-term care. Many people stay connected to their IDDT team for years, even after symptoms improve.

Can IDDT help someone with mild mental illness and occasional drug use?

Yes. While IDDT was originally designed for severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, its principles apply to anyone with co-occurring conditions. Even mild anxiety or depression paired with regular marijuana or alcohol use can benefit from integrated care. The team helps identify how the two interact and builds personalized strategies - whether that’s cutting back, changing patterns, or seeking therapy.

Why is IDDT so hard to implement widely?

Three main barriers: funding, training, and system fragmentation. Most insurance doesn’t cover integrated care as a single service, so clinics lose money. Training clinicians to be experts in both mental health and addiction takes time and money - and many programs don’t offer it. Plus, mental health and addiction services are often housed in separate buildings with different rules, making coordination difficult. Without policy changes and investment, IDDT remains available only in pockets of the country.

8 Comments

Frank BaumannFebruary 10, 2026 AT 23:05

Let me tell you something I've seen firsthand-this isn't just theory, it's survival. I watched my brother cycle through rehab centers, therapists, ER visits, and jail cells because no one ever connected the dots. One guy told him to quit drinking cold turkey; another prescribed him antipsychotics that made him vomit if he so much as smelled beer. He was drowning in contradictions. Then he got into an IDDT program. Same team. Same room. Same damn calendar. They didn't care if he drank on day one-they cared if he showed up. And he did. Every. Single. Time. Now he’s got a job, a dog, and a girlfriend who doesn’t flinch when he says, 'I need to call my counselor.' This isn't magic. It’s coordination. And if you’re still treating mental health and addiction like separate crimes, you’re not helping-you’re just moving bodies between boxes.

Also-why the hell are we still using insurance codes from the 1990s? This system is built on silos because bureaucracy hates complexity. But real people? They don’t have separate diagnoses. They just have pain. And they deserve a team that sees them whole.

Alex OgleFebruary 11, 2026 AT 21:31

I’m not one for grand statements, but I’ve worked in community mental health for 17 years, and I’ve seen IDDT change lives in ways I never thought possible. The biggest shift? We stopped treating symptoms and started treating people. One guy I worked with-schizophrenia, meth addiction, no stable housing-he didn’t want to quit drugs. So we didn’t push. We talked about how smoking meth made his hallucinations worse at night. We got him a sleep mask. We linked him to a needle exchange. We slowly built trust. Six months later, he stopped using. Not because we demanded it. Because he felt seen. That’s the power of integrated care. Not the shiny protocols. Not the funding grants. The quiet, consistent presence of someone who refuses to look away.

And yeah, the data’s good. But the real win? When someone says, 'I don’t feel like a problem anymore.' That’s worth more than any ROI calculation.

Tatiana BarbosaFebruary 13, 2026 AT 15:26

This is the kind of care that actually saves lives not just manages symptoms. I’ve been on both sides-patient and peer specialist-and IDDT is the only thing that made me feel like I mattered. No judgment. No ultimatums. Just someone who showed up and said, 'Let’s figure this out together.' We need this everywhere. Not just in New Hampshire. Not just in fancy pilot programs. Everywhere. The system’s broken but this model? It’s the fix.Random GuyFebruary 15, 2026 AT 13:44

So wait… you’re telling me if I’m a depressed alcoholic who also hates his job and his mom, we’re supposed to just… hug it out and call it ‘integrated care’? Bro. I got a 12-step program, a therapist, and a guy on Reddit who says ‘just quit’ and that’s all I need. This sounds like a government-funded therapy cult. Give me abstinence or give me death. Also, why does everyone in these stories get a dog and a GED? Real talk: most of us just want to sleep and not feel guilty about it.Ryan VargasFebruary 16, 2026 AT 20:54

Let’s be brutally honest: this entire model is a distraction from the real issue-the pharmaceutical-industrial complex’s commodification of human suffering. The FDA, SAMHSA, and CDC didn’t endorse IDDT because it’s effective. They endorsed it because it creates a new revenue stream. Look at the funding structure: state grants, federal reimbursements, Medicaid waivers. Every time someone enters an ‘IDDT program,’ a bureaucrat gets paid. The nine core components? They’re not therapeutic-they’re billing codes. And the woman in the example who got her GED? She’s a marketing case study. Real recovery doesn’t happen in structured group sessions with motivational interviewing scripts. It happens in isolation, in silence, in the dark, when the system isn’t watching. This isn’t healing. It’s institutionalization with better PR.

And don’t get me started on harm reduction. It’s not compassion-it’s surrender. If we stop demanding abstinence, we’re saying addiction is acceptable. That’s not healthcare. That’s cultural decay.

Tasha LakeFebruary 18, 2026 AT 06:02

I’m a clinician in rural Ohio and we just launched our first IDDT pilot last year. The training was intense but transformative. We had to unlearn so much-like how to talk to someone who’s using while also managing psychosis. It’s not about fixing them. It’s about walking with them. One client said, 'No one’s ever asked me how the meds make me feel when I’m high.' That hit me. We’re not just treating disorders-we’re rebuilding dignity. The data’s promising, but the real metric? When someone says, 'I think I can live like this.' That’s the moment you know it’s working.Sam DickisonFebruary 19, 2026 AT 00:23

I’ve been in recovery for 8 years. Used to be a heroin addict with bipolar II. Went through every kind of treatment. IDDT was the first time someone didn’t treat me like a problem to solve. My counselor didn’t care if I smoked weed-he cared if I was sleeping. If I was eating. If I was calling my mom. We didn’t even talk about quitting until year two. And when I did? I quit because I wanted to, not because I was told to. That’s the difference. You don’t fix people. You help them find their own way back. Simple. Human. Effective.Brett PouserFebruary 19, 2026 AT 13:07

I’m from Nigeria and we don’t have IDDT here. But I’ve seen how stigma kills. My cousin had schizophrenia and used kola nuts to self-medicate. They called it 'witchcraft.' No one offered therapy, meds, or harm reduction. Just prayers and chains. This post? It’s not just about policy. It’s about humanity. We treat addiction like sin. Mental illness like weakness. But it’s biology. It’s trauma. It’s survival. IDDT doesn’t fix the system. It just reminds us that people aren’t broken-they’re trying.