Liver Drug Clearance Calculator

Medication Safety Calculator

Estimate safe medication doses based on liver function and drug extraction type

When your liver is damaged, it doesn’t just affect how you feel-it changes how your body handles every pill you take. Many people assume that if a drug works for someone with a healthy liver, it will work the same way for someone with cirrhosis or fatty liver disease. That’s not true. In fact, reduced clearance due to liver disease is one of the most underrecognized risks in modern prescribing. It’s why a standard dose of a sedative can send a cirrhotic patient into hepatic encephalopathy, or why an antibiotic might cause toxic spikes in blood levels. This isn’t theoretical. It’s happening every day in clinics and hospitals across the U.S., where over 22 million people live with chronic liver disease.

Why the Liver Matters for Every Drug You Take

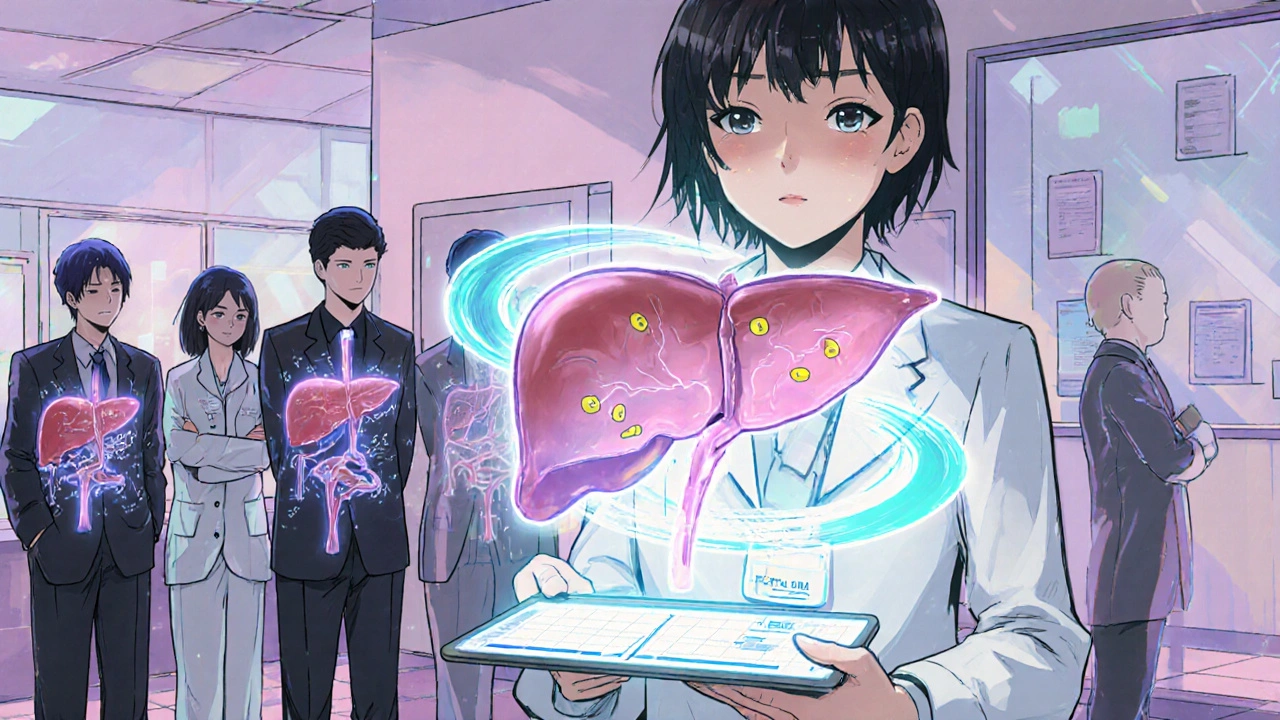

The liver isn’t just a filter. It’s the main factory for breaking down drugs. About 70% of commonly prescribed medications rely on liver enzymes-especially the cytochrome P450 family-to be processed and cleared from the body. When liver function drops, those enzymes slow down. In advanced cirrhosis, CYP3A4 activity can drop by 30-50%, and CYP2E1 by up to 60%. That means drugs like morphine, diazepam, and warfarin stick around much longer than they should. But it’s not just about enzymes. Liver disease also messes with blood flow. Healthy livers get about 1.5 liters of blood per minute. In cirrhosis, that drops to 0.8-1.0 liters. Worse, up to 40% of that blood bypasses the liver entirely through abnormal connections called portosystemic shunts. So even if the liver cells are still trying to work, a big chunk of the drug never even reaches them.High-Extraction vs. Low-Extraction Drugs: The Key Difference

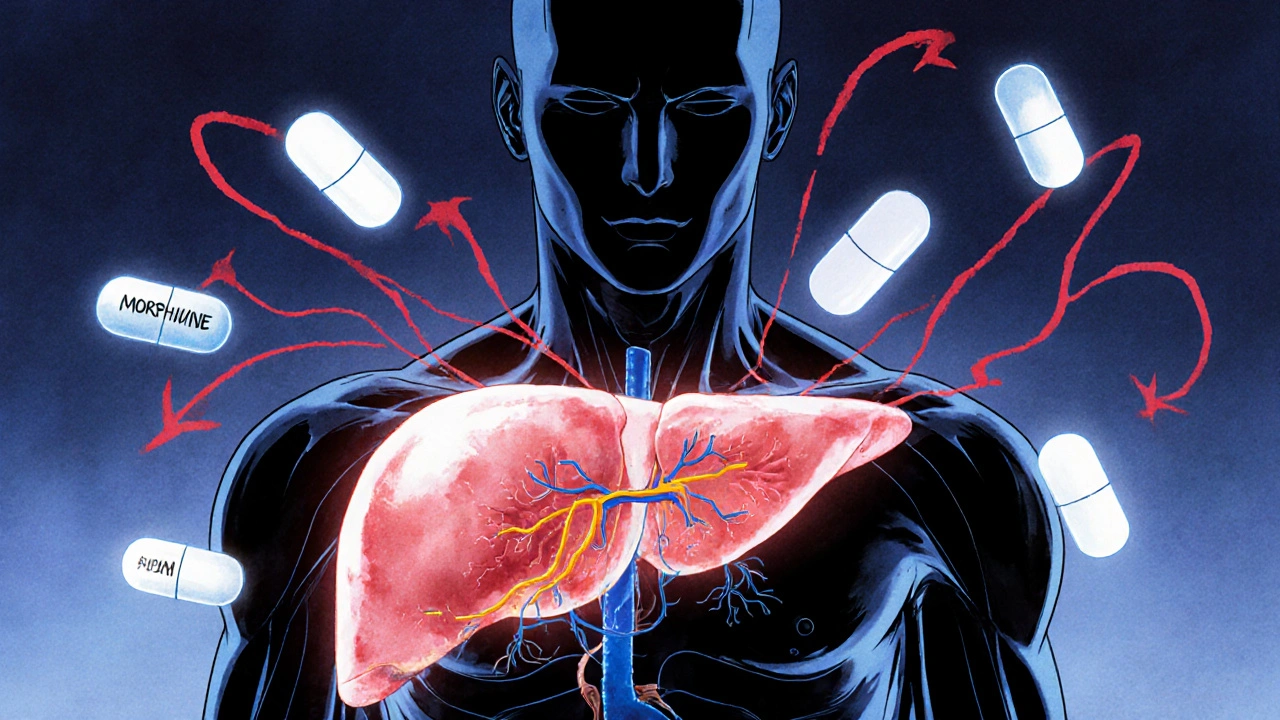

Not all drugs are affected the same way. The difference comes down to something called the extraction ratio.- High-extraction drugs (ratio >0.7) depend on blood flow. Examples: fentanyl, morphine, propranolol. If blood flow drops, clearance drops. Dose reductions of 50-75% are often needed in severe liver disease.

- Low-extraction drugs (ratio <0.3) depend on enzyme activity. Examples: lorazepam, diazepam, methadone, warfarin. These are the real troublemakers. Since they’re metabolized slowly even in healthy people, any drop in enzyme function causes big changes. About 70% of all common prescriptions fall into this category.

What Happens When Drugs Build Up

The consequences aren’t just theoretical. They’re dangerous-and often silent.- Warfarin: Clearance drops by 30-50% in cirrhosis. A standard 5 mg dose can push INR levels into dangerous territory. Most patients need 25-40% less.

- Opioids and sedatives: The brain becomes 30-50% more sensitive to these drugs in liver disease. Even small doses can trigger confusion, drowsiness, or coma. Hepatic encephalopathy can develop within hours.

- Antibiotics: Ceftriaxone levels can spike 40-60% higher in cirrhotic patients. That’s not just a lab curiosity-it’s linked to increased risk of kidney injury and allergic reactions.

- Direct-acting antivirals (DAAs): In patients with Child-Pugh C cirrhosis, improper dosing led to 22.7% treatment failure in one major study. That’s more than 1 in 5 people not cured because the dose wasn’t adjusted.

How Doctors Assess Liver Function-And Why It’s Not Just About Lab Numbers

You might think: “Just check the bilirubin or ALT.” But that’s not enough. Liver disease doesn’t follow a simple pattern. Two people with the same bilirubin level can have wildly different drug clearance. That’s why guidelines use two tools:- Child-Pugh Score: Based on bilirubin, albumin, INR, ascites, and mental status. Class A (mild), B (moderate), C (severe). For Class B, most drugs need 25-50% dose reduction. For Class C, it’s 50-75%.

- MELD Score: Uses bilirubin, INR, and creatinine. Every 5-point increase above 10 means about 15% less drug clearance. It’s especially useful for predicting outcomes in transplant candidates.

When You Don’t Need to Change the Dose

Not every drug needs adjustment. There are two safe exceptions:- Drugs cleared entirely by the kidneys: Sugammadex, for example, is 96% excreted unchanged in urine. No dose change needed-even in severe liver disease.

- Drugs with minimal liver metabolism (<20%) and a wide safety margin: Some NSAIDs and antihistamines fall here. But even then, watch for side effects. The liver isn’t the only organ affected by disease.

What’s Changing in Drug Development

The industry is catching up. In 2023, the FDA approved 18 new drugs with specific dosing instructions for liver disease-up 25% from the year before. Nearly all new drug applications now include hepatic impairment studies, up from 65% in 2018. New tools are emerging too. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling can now predict drug levels in cirrhotic patients with 85-90% accuracy. These models factor in blood flow, enzyme levels, shunting, and even body composition. The FDA’s 2024 draft guidance pushes for this approach in labeling. Within five years, most new drug labels will include model-based dosing recommendations-not just vague warnings. And it’s not just about cirrhosis anymore. Early-stage fatty liver disease (MASLD), which affects 30% of U.S. adults, can reduce CYP3A4 activity by 15-25% even before scarring appears. That means millions of people with “mild” liver issues may already be at risk for drug accumulation.What Patients and Providers Can Do Today

You don’t need a fancy model to make safer choices.- Always ask: “Is this drug cleared by the liver?” If yes, assume it needs adjustment.

- Use Child-Pugh or MELD scores. Don’t rely on ALT or AST alone.

- Start low, go slow. Especially with opioids, benzodiazepines, and anticoagulants.

- Consider therapeutic drug monitoring. For drugs like warfarin, phenytoin, or tacrolimus, checking blood levels can prevent disasters.

- Watch for new symptoms. Confusion, excessive sleepiness, or unexplained bleeding could mean drug buildup-not just worsening liver disease.

The Bottom Line

Liver disease doesn’t just mean jaundice or fatigue. It means your body can’t clear drugs the way it used to. That’s not a minor detail-it’s a life-or-death shift in how medications behave. Ignoring it leads to preventable harm. Adjusting for it saves lives. The tools are here: scoring systems, drug databases, pharmacokinetic models, and clearer guidelines. What’s missing is awareness. If you’re treating someone with liver disease, don’t assume their meds are safe just because they’ve always taken them. Recheck. Reassess. Adjust.Does liver disease always require lower drug doses?

No-not always. Drugs cleared mostly by the kidneys (like sugammadex or most antibiotics) don’t need dose changes. Also, drugs with minimal liver metabolism (<20%) and a wide safety margin may be safe at standard doses. But if a drug is metabolized by the liver, assume it needs adjustment unless proven otherwise.

Can I use a patient’s ALT or AST level to decide on dosing?

No. ALT and AST measure liver cell damage, not function. A patient with normal ALT but low albumin and high bilirubin may have severe liver impairment. Always use Child-Pugh or MELD scores, which assess actual liver function, not just inflammation.

Why does diazepam cause more problems than lorazepam in liver disease?

Diazepam breaks down into active metabolites that stick around for days, building up in the body. Lorazepam is metabolized differently and doesn’t produce long-lasting active byproducts. So even though both are benzodiazepines, diazepam is much riskier in liver disease-requiring 50-70% dose reduction, while lorazepam may only need 25-40%.

Is fatty liver disease (MASLD) a concern for drug metabolism?

Yes. Even early-stage fatty liver without scarring can reduce CYP3A4 enzyme activity by 15-25%. That means common drugs like statins, calcium channel blockers, and some antidepressants may build up more than expected. This is often overlooked because patients feel fine-but the metabolic risk is real.

What’s the best way to avoid medication errors in liver disease?

Use the Child-Pugh or MELD score to assess severity, check the drug’s primary clearance route, start with lower doses, and monitor for side effects like confusion, drowsiness, or bleeding. For high-risk drugs (warfarin, opioids, antiepileptics), therapeutic drug monitoring is the gold standard. When in doubt, consult a pharmacist or hepatologist.

Therapeutic drug monitoring isn’t just for hospitals anymore. As the market for liver-specific monitoring tools grows toward $1.24 billion by 2026, more clinics are adopting it. The goal isn’t to complicate care-it’s to make it safer. Because when the liver fails, the body doesn’t fail gracefully. It just holds onto the drugs-and the consequences can be deadly.

14 Comments

Gus FosarolliNovember 28, 2025 AT 22:57

So let me get this straight - we’re giving the same dose of morphine to someone with cirrhosis as we do to a 25-year-old who just did a keg stand? 😅

That’s not medicine, that’s Russian roulette with a prescription pad.

And don’t even get me started on how often nurses have to double-check if the patient’s chart says ‘liver disease’ or just ‘drank too much last night’.

Evelyn Shaller-AuslanderNovember 30, 2025 AT 15:17

i’ve seen this happen. my dad got diazepam after surgery, didn’t know he had fatty liver. slept for 3 days. woke up confused. no one told the doc his liver was messed up.

we need better flags in ehr systems.

Paul BakerNovember 30, 2025 AT 23:46

bro this is wild 🤯

so if you got cirrhosis your body just becomes a drug sponge??

no wonder my uncle’s meds always made him weird 😅

Zack HarmonDecember 1, 2025 AT 04:17

THIS IS A MASSACRE. A MEDICAL MASSACRE.

Doctors are literally killing people with ignorance.

70% of drugs? That’s not a statistic - that’s a death sentence waiting to happen.

And who’s paying for it? The families. The ERs. The funeral homes.

They don’t teach this in med school because they don’t want to admit how broken the system is.

Jeremy S.December 2, 2025 AT 13:49

Yeah this is real. I work in ER. We see it weekly.

Simple fix: always ask about liver history before prescribing.

Easy. Cheap. Life-saving.

Jill Ann HaysDecember 2, 2025 AT 14:23

It is imperative to recognize that hepatic metabolism constitutes a pivotal physiological determinant in pharmacokinetic outcomes, particularly in the context of compromised enzymatic function associated with chronic parenchymal degeneration.

Failure to account for this variable constitutes a fundamental deviation from evidence-based therapeutic paradigms.

Mike RothschildDecember 3, 2025 AT 09:59

My brother’s a hepatologist. He says the biggest problem isn’t the drugs - it’s the assumption that ‘normal dose’ means ‘safe dose.’

Every time someone says ‘it worked for my cousin,’ we lose another patient.

Simple rule: if liver’s bad, cut the dose. Start low. Go slow.

No magic formulas. Just common sense.

Ron PrinceDecember 3, 2025 AT 15:05

So now we’re coddling drunks with special pill rules?

My grandpa worked 40 years, paid taxes, never touched booze - but now some guy who drank himself into a coma gets a 75% discount on his meds?

That’s not fairness. That’s socialism for addicts.

Sarah McCabeDecember 4, 2025 AT 06:13

lol i just realized my favorite painkiller is one of those high-extraction drugs 😅

guess i better ask my doc before i keep popping them like candy 🍬

King SplinterDecember 6, 2025 AT 02:33

Look, I read the whole thing and honestly? This is just another overcomplicated medical blog post trying to sound smart.

People don’t need to know about CYP3A4 or extraction ratios.

They just need to know: if you have liver damage, don’t take meds unless your doctor says so.

That’s it. Everything else is noise.

Also, why does everything have to be 500 words? I’m not writing a thesis.

Kristy SanchezDecember 7, 2025 AT 05:27

It’s not about the drugs.

It’s about how we treat people who are broken.

We see liver disease as a moral failure, not a medical condition.

And then we punish them with poison pills because we can’t handle the guilt of knowing we didn’t help them sooner.

So we just write the script and pretend we did our job.

It’s not science.

It’s shame.

Michael FriendDecember 7, 2025 AT 21:36

They don’t want you to know this.

Pharma doesn’t want you to know that their $12,000 pill might kill you if you’ve had one beer too many.

Hospitals don’t want to admit they’ve been dosing people wrong for decades.

This is a cover-up wrapped in a white coat.

And now they want you to ‘trust the science’?

Trust who? The same people who gave you opioids and called it ‘pain management’?

Jerrod DavisDecember 8, 2025 AT 07:01

It is submitted for consideration that the hepatic clearance of xenobiotics is subject to significant alteration in the presence of parenchymal fibrosis and architectural distortion, thereby necessitating individualized pharmacokinetic recalibration.

Failure to implement such recalibration constitutes a deviation from the standard of care as defined by the American College of Gastroenterology, 2023 edition.

Dominic FuchsDecember 8, 2025 AT 20:25

Interesting. I once had a GP give me codeine after a dental job. I told him I had hepatitis C. He said, 'Oh, you’ll be fine.'

Turned out I was fine. But barely.

Turns out 'fine' isn't the same as 'safe'.

Maybe we need to stop assuming people know their own bodies better than the chart does.