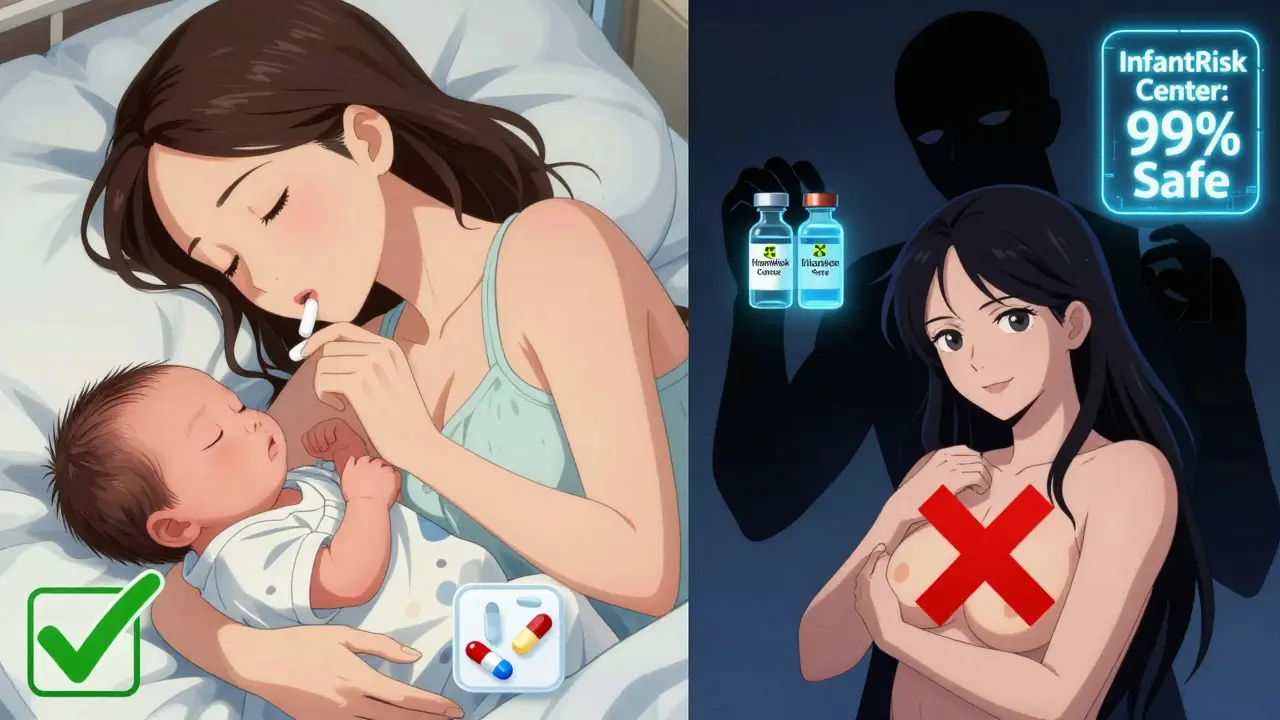

When you’re breastfeeding, every pill you take feels like a gamble. Will it reach your baby? Will it harm them? Will you have to stop nursing? These fears are real-and they’re why so many mothers quit breastfeeding earlier than they want to. But the truth is, most medications are safer than you think. The key isn’t avoiding medicine-it’s understanding how it moves into your milk, and what that actually means for your baby.

How Medications Get Into Breast Milk

Medications don’t swim through your body and magically appear in your breast milk. They follow the same rules as everything else that moves between your blood and your milk: physics and chemistry. About 75% of drugs cross into milk through passive diffusion. That means they drift from areas of high concentration (your bloodstream) to low concentration (your milk), just like ink spreading in water. This happens because the cells lining your milk ducts aren’t sealed shut-they have tiny gaps that let small, fat-soluble molecules slip through easily. The other 25% use special transport systems. Some drugs, like the antibiotic nitrofurantoin or the heartburn med cimetidine, hitch a ride on proteins that normally move nutrients or waste. These are called carrier-mediated transporters. They’re picky-they only move certain molecules. That’s why some drugs barely show up in milk, even if they’re small and fat-soluble. Size matters. Drugs heavier than 800 daltons-like heparin (15,000 daltons)-almost never get through. That’s why blood thinners like heparin are safe during breastfeeding. But tiny drugs like lithium (74 daltons) slip right through. In fact, lithium can reach up to 10% of your weight-adjusted dose in your baby’s system. That’s why doctors monitor lithium levels closely in nursing mothers. Fat solubility is another big factor. Drugs that dissolve easily in fat-like diazepam-build up in milk. Its milk-to-plasma ratio can hit 1.5 to 2.0, meaning there’s more of it in your milk than in your blood. On the flip side, water-soluble drugs like gentamicin barely make it into milk. Their ratio is around 0.05 to 0.1. That’s why antibiotics like amoxicillin and cephalexin are considered low-risk. Protein binding is the silent gatekeeper. Most drugs in your blood stick to proteins like albumin. Only the free, unbound portion can cross into milk. If a drug is 99% bound-like warfarin-less than 0.1% ends up in your milk. Sertraline is 98.5% bound, yet still shows up in milk. Why? Because even a tiny fraction of a powerful drug can be enough to affect a baby.The pH Trap: Why Some Drugs Concentrate in Milk

Your milk is slightly more acidic than your blood-pH 7.0 to 7.4 versus 7.4. That small difference creates something called ion trapping. Weak bases-drugs that pick up a positive charge in acidic environments-get caught in milk. Once they enter, they can’t easily escape back into your blood. That’s why drugs like amitriptyline (an antidepressant with a pKa of 9.4) can reach milk concentrations two to five times higher than in your blood. The same thing happens with pseudoephedrine, some antihistamines, and even caffeine. It’s not that these drugs are dangerous-it’s that your body unintentionally concentrates them in milk. That’s why timing matters. Taking your dose right after feeding gives your body time to clear some of the drug before the next session.Early Milk: A Different Game

In the first few days after birth, your milk isn’t like regular breast milk. The cells in your mammary glands haven’t fully sealed together yet. Gaps between them are 10 to 20 nanometers wide-big enough for even large molecules like antibodies and some medications to slip through. That’s why colostrum has high levels of immunoglobulins: your body is deliberately dumping protective proteins into your baby’s first meals. But that also means medications can transfer more easily during this window. After day 10, those gaps close by 90%. So if you’re starting a new medication right after birth, your baby may get more of it than if you started a week later. This isn’t a reason to avoid meds-it’s a reason to time them wisely.

What Counts as a Dangerous Dose?

You don’t need to panic because your baby gets a trace of your medication. The real question is: how much of your dose are they actually getting? Most drugs result in infant exposure under 10% of your weight-adjusted dose. That’s the threshold the CDC uses to define safety. For antibiotics, it’s often under 3%. For antidepressants, it’s usually 1-2%. Even diazepam, which transfers well, only delivers about 7.3% of your dose to your baby. But here’s the catch: babies aren’t small adults. Their livers and kidneys are still learning how to process drugs. A drug that clears quickly in you might linger for days in a newborn. Diazepam’s half-life in a newborn can be 30 to 100 hours-versus 20-100 in adults. That means it can build up over time. That’s why doctors recommend checking infant serum levels if you’re on more than 10 mg of diazepam daily. For SSRIs like sertraline, the InfantRisk Center advises checking baby’s blood levels at two weeks postpartum. Watch for signs: irritability (seen in 8.7% of cases), poor feeding (5.3%), or excessive sleepiness. If levels exceed 10% of your therapeutic dose, talk to your doctor about alternatives.Medications That Are Safe (and Those That Aren’t)

The good news? Most meds are safe. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, 87% of commonly prescribed drugs fall into the “usually compatible” category. That includes:- Insulin (no transfer)

- Heparin (too big to pass)

- Amoxicillin, cephalexin (low transfer)

- Sertraline, paroxetine (low infant exposure)

- Acetaminophen and ibuprofen (minimal transfer)

- Radioactive iodine-131 (used for thyroid cancer): Must stop breastfeeding for weeks.

- Chemotherapy drugs (like methotrexate): Avoid while nursing.

- High-dose estrogen birth control (over 50 mcg ethinyl estradiol): Can slash milk supply by 40-60% in 72 hours.

- Bromocriptine: Used to stop lactation-95% effective, but not for nursing moms.

When and How to Take Your Meds

Timing isn’t just helpful-it’s strategic. Taking your medication right after you nurse gives your body 3 to 4 hours to clear the drug before the next feeding. That can cut your baby’s exposure by 30-50%. For long-acting drugs, this is even more important. Avoid taking meds right before bed if your baby nurses overnight. That’s when plasma levels peak. Instead, take your dose after the last feeding of the day. If you’re on a daily medication, stick to the same time each day. Consistency helps your body build a rhythm-and makes it easier to predict when levels are lowest.

What to Watch For in Your Baby

Most babies show no signs at all. But if you notice:- Excessive sleepiness or difficulty waking to feed

- Unusual fussiness or crying that won’t stop

- Poor feeding or weight gain that slows

- Jaundice that doesn’t improve

9 Comments

Adewumi GbotemiJanuary 11, 2026 AT 02:00

Man, this is the kind of info I wish I had when I was nursing. So many moms panic over pills like they're poison, but most are fine. Just take it after feeding and watch your baby. No need to quit over fear.

Madhav MalhotraJanuary 11, 2026 AT 12:44

From India, we've always trusted Ayurveda, but this science-backed breakdown is eye-opening. Even my aunt, who swore off meds while breastfeeding, now asks her doctor for LactMed before taking anything. Knowledge is power.

Priya PatelJanuary 13, 2026 AT 10:46

I was on sertraline while nursing my twins and no one told me about the 10% threshold. My oldest was super sleepy at first-I thought it was just newborn stuff. Turns out, it was the meds. Took me 3 weeks to figure it out. This post saved my sanity.

Sean FengJanuary 15, 2026 AT 08:37

So what you're saying is if I take a pill after nursing I'm not a bad mom? Wow. Groundbreaking. I'm gonna start writing this on my fridge.

Christian BaselJanuary 16, 2026 AT 23:42

Passive diffusion dominates pharmacokinetic transfer across the mammary epithelium due to lipid solubility and molecular weight thresholds under 800 Da, while ion trapping in alkaline milk matrices amplifies bioavailability of weak bases with pKa >7.4. Protein binding >95% reduces free fraction to <0.5%, rendering most SSRIs clinically negligible despite detectable concentrations. But let's not forget neonatal CYP450 immaturity-half-lives can extend 3x, creating non-linear accumulation risk. LactMed is still the gold standard, but the 2024 MOMS study will redefine thresholds.

Jason ShrinerJanuary 18, 2026 AT 10:39

So basically, if you're not a pharmacologist, you're just supposed to trust some app that uses 'AI' to tell you it's okay? Sounds like a Silicon Valley scam wrapped in a baby blanket. Next they'll tell us our tears are safe for the baby.

Vincent ClarizioJanuary 18, 2026 AT 11:55

Think about it-your body is a temple, but it's also a factory. And your milk? It's not just food, it's a biofluid conduit shaped by evolution, chemistry, and the quiet, relentless work of your cells. You think you're just popping a pill? No. You're orchestrating a silent molecular ballet where tiny ions drift across membranes, proteins lock and unlock like gates, and your baby, helpless and perfect, receives a fraction of your healing. That's not magic. That's biology. And it's beautiful. So stop fearing your meds. Honor them. Time them. Respect the science. Your baby isn't getting poison-they're getting your love, translated into molecules.

Alex SmithJanuary 20, 2026 AT 08:35

Christian, you just turned a breastfeeding guide into a textbook chapter. Cool. But what does this mean for a mom at 3am with a screaming baby and a 10mg dose of diazepam? Can we get a TL;DR that doesn't require a PhD? Also, why is the FDA only now requiring lactation data? That's 2024, not 1924.

Roshan JoyJanuary 21, 2026 AT 10:01

Great breakdown. I'm a dad, and I read this to my wife last night. She was crying because she thought she had to choose between meds and breastfeeding. Now she's texting her OB with LactMed links. Small wins, right? 💪🍼