Ethical Checklist for Skin-Invading Parasite Research

This interactive tool helps you identify and address key ethical considerations when researching skin-invading parasites. Use the tabs below to navigate through the main ethical domains and track your progress.

Human Subjects Ethics Checklist

Animal Use Ethics Checklist

Biosafety Checklist

Dual-Use Research Checklist

Cultural Sensitivity Checklist

Ethical Review Summary

This section will show your progress and identify areas needing attention.

When scientists study parasites that burrow into skin or lay eggs beneath it, the work can lead to breakthrough treatments for diseases like cutaneous larva migrans or onchocerciasis. But the same research also raises tough ethical questions. This article breaks down the main concerns-human subjects, animal use, lab safety, dual‑use risks, and cultural sensitivities-and offers a practical checklist to help researchers act responsibly.

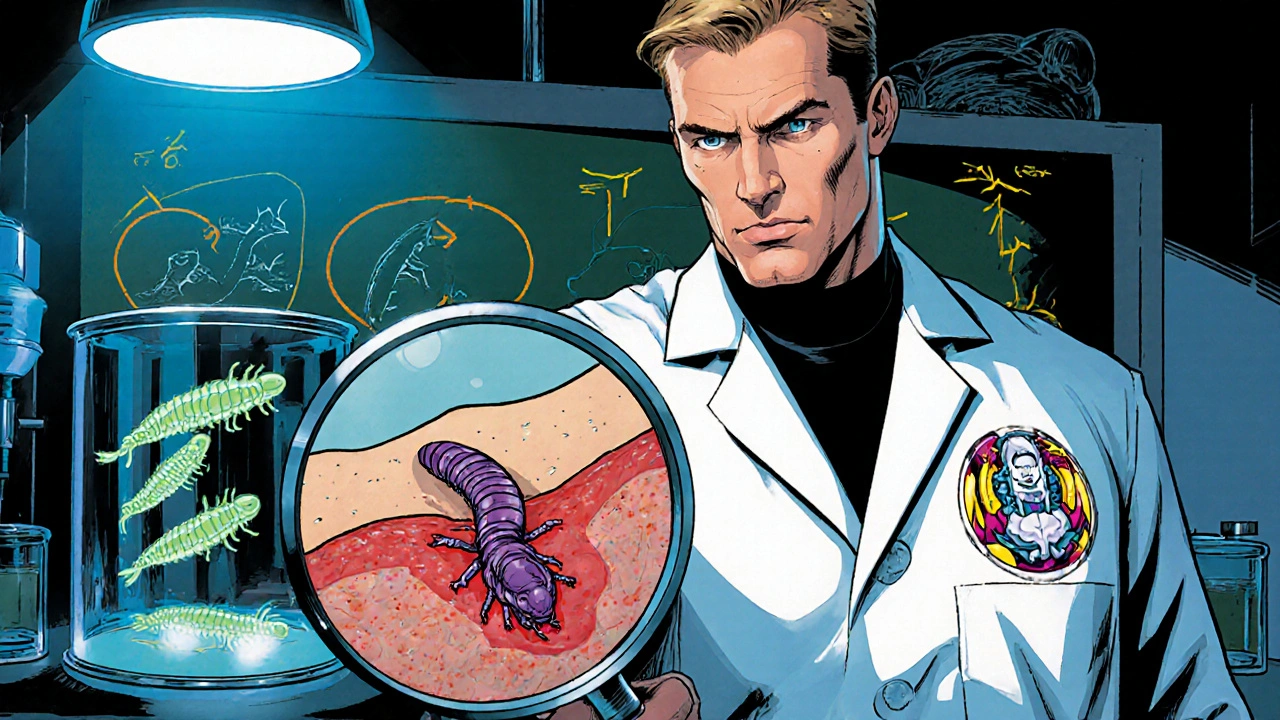

What are skin‑invading parasites?

Skin‑invading parasites are organisms that either live within the dermis or deposit their eggs there, causing a range of cutaneous conditions. Common examples include Strongyloides stercoralis larvae, the filarial worm Onchocerca volvulus, and the tick‑borne Sarcoptes scabiei. Their life cycles often involve complex host interactions, making them attractive-yet tricky-subjects for biomedical research.

Why ethics matter in parasite research

Studying these organisms isn’t just about lab techniques; it touches on the core values of biomedical science. Poorly designed studies can exploit vulnerable communities, cause unnecessary animal suffering, or generate data that could be misused for harmful purposes. By foregrounding ethics, researchers protect participants, preserve public trust, and ensure that scientific gains translate into real health benefits.

Human participant protection

Informed consent is the bedrock of ethical human research. When trials involve patients with active skin infections or healthy volunteers exposed to parasite larvae, consent forms must clearly explain risks-such as allergic reactions, secondary infections, or long‑term skin damage.

- Use plain language: avoid medical jargon that can obscure real dangers.

- Provide visual aids showing how the parasite enters the skin and what participants might experience.

- Offer the option to withdraw at any point without penalty.

Vulnerable groups-children, the elderly, and individuals in low‑resource settings-need extra safeguards. Community advisory boards (CABs) can review consent materials and ensure they respect local customs.

Animal welfare considerations

Many skin‑parasite studies rely on animal models, especially rodents and non‑human primates, to replicate the dermal lifecycle. The principle of Replacement, Reduction, Refinement (the 3Rs) must guide every protocol.

- Replacement: Whenever possible, use in‑vitro skin cultures, organ‑on‑a‑chip systems, or computational models.

- Reduction: Conduct power calculations to avoid excess animal numbers.

- Refinement: Employ analgesics, humane endpoints, and minimally invasive sampling to lessen pain.

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUCs) should evaluate not only the scientific merit but also the justification for each species used. Transparent reporting of animal numbers and welfare outcomes is essential for reproducibility and accountability.

Biosafety and containment

Working with live larvae or eggs that can infect humans demands strict biosafety protocols. Laboratories should be classified according to the risk level of the organism (e.g., BSL‑2 for most skin‑invading parasites, BSL‑3 for highly pathogenic strains).

- Implement double‑door entry, directional airflow, and autoclave decontamination for waste.

- Train all staff in proper donning/doffing of personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Maintain an incident‑reporting system for accidental exposures.

Regular audits by biosafety officers keep practices up to date and demonstrate compliance with national regulations such as the U.S. CDC/NIH guidelines or the EU’s Biological Agents Directive.

Dual‑use research and societal impact

Parasite biology can be a double‑edged sword. Knowledge that helps develop vaccines could also be misused to create more virulent strains or bioterror agents. The concept of dual‑use research of concern (DURC) calls for a risk‑benefit assessment before publishing sensitive data.

- Identify experiments that could enable harmful applications (e.g., increasing parasite infectivity).

- Engage with biosecurity experts to gauge the likelihood of misuse.

- Consider redacting or delaying the release of detailed methodological data while still providing sufficient information for scientific replication.

Funding agencies increasingly require DURC statements, and journals may ask for special review panels when manuscripts involve high‑risk findings.

Cultural and community engagement

Skin‑related parasitic diseases often affect marginalized populations in tropical regions. Researchers must respect local beliefs about skin conditions, which can be linked to spiritual or social stigma.

- Partner with local health workers to co‑design study protocols.

- Provide educational sessions that demystify the parasite’s life cycle and the purpose of the research.

- Ensure that any benefits-such as free treatment or capacity building-are shared with the community.

By acknowledging cultural context, scientists avoid exploiting fear or misinformation and foster long‑term collaboration.

Ethical checklist for skin‑invading parasite research

| Domain | Primary Concern | Actionable Checklist |

|---|---|---|

| Human Subjects | Informed consent clarity | Plain‑language consent forms; visual aids; withdrawal option; CAB review. |

| Animal Use | 3Rs compliance | Explore in‑vitro alternatives; power‑calc for sample size; analgesia protocols. |

| Biosafety | Containment level | Assign appropriate BSL; PPE training; autoclave waste; incident reporting. |

| Dual‑use | Potential misuse | Risk‑benefit analysis; consult biosecurity experts; consider data redaction. |

| Cultural Sensitivity | Community trust | Co‑design with locals; education sessions; equitable benefit sharing. |

Practical steps for implementing ethical standards

- Draft a comprehensive protocol that integrates the checklist above.

- Submit the protocol to both an IRB (for human work) and an IACUC (for animal work) simultaneously.

- Schedule a biosafety inspection before any live parasite work begins.

- Hold a pre‑study meeting with community leaders and a biosecurity advisor.

- Document every decision point-what was changed, why, and who approved it.

- During the study, keep a real‑time log of adverse events, containment breaches, or participant concerns.

- After data collection, perform a final ethical review to confirm that all obligations were met before manuscript preparation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do I need an IRB approval for studies that only use parasite eggs?

Yes. Even if the work involves only parasite eggs, the study may affect human participants-through skin exposure, sample collection, or future therapeutic use. An IRB reviews consent processes, risk assessments, and community impact.

Can I replace animal models with organ‑on‑a‑chip technology for all skin‑parasite studies?

Not yet for every question. While skin‑on‑a‑chip platforms mimic many aspects of human dermal biology, they can’t fully replicate systemic immune responses or parasite migration patterns that require a whole‑organism context. Use them where possible and supplement with minimal animal work when necessary.

What biosafety level is required for Onchocerca volvulus larvae?

The CDC classifies O. volvulus as a BSL‑2 agent, but many institutions upgrade to BSL‑3 when handling large inocula or performing genetic modifications because of the risk of accidental skin penetration.

How should I address dual‑use concerns when publishing my methods?

Include a brief DURC statement in the manuscript, outline the risk assessment you performed, and work with the journal’s security editor to decide if any detailed steps need redaction. Providing enough information for replication while omitting sensitive parameters is the usual balance.

What is the best way to involve the community in research on skin parasites?

Form a community advisory board early, co‑create consent materials, hold open forums to explain study goals, and ensure that any health interventions (e.g., deworming campaigns) are offered to participants regardless of study enrollment.

11 Comments

Jonathan SOctober 15, 2025 AT 19:43

It is absolutely indefensible that researchers would cavalierly expose vulnerable populations to skin‑penetrating parasites without a bullet‑proof ethical framework 😡. The sanctity of informed consent must be upheld with crystal‑clear language, not the obfuscating jargon that so often shrouds protocol documents 😤. Any attempt to gloss over the risk of secondary infections betrays a profound disrespect for human dignity 😠. Researchers have a moral obligation to embed community advisory boards from the outset, lest they become perpetrators of neo‑colonial exploitation 🚫. The use of animal models must be rigorously justified under the 3Rs, and any deviation should be publicly disclosed with detailed welfare metrics 📊. Biosafety cannot be an afterthought; double‑door containment and incident reporting are non‑negotiable safeguards 🛡️. Dual‑use considerations are not optional academic exercises; they are essential to prevent malicious exploitation of pathogenic knowledge 🧬. Cultural sensitivity is not a box‑ticking exercise but a cornerstone of trust‑building with marginalized groups 🙏. The checklist provided in the article should be treated as a living document, revisited after every pilot study 🗂️. Transparency in reporting animal numbers and human participant demographics is the only pathway to reproducibility and public trust 📈. Funding agencies must enforce DURC statements, and journals should demand redaction of only the truly dangerous details, not the entire methodological corpus 📚. Ethical oversight committees should operate in tandem, not in silos, to harmonize human and animal protections 🤝. The ultimate goal of alleviating disease burden does not excuse corner‑cutting or ethical shortcuts 🏥. Researchers must remember that every dermal invasion they study has a human counterpart suffering in the field 🧑⚕️. Only by upholding these standards can science claim the moral high ground it so desperately needs 🌟.

Charles MarkleyOctober 24, 2025 AT 07:43

While the moralistic rant above bemoans ethical lapses, it fails to engage with the ontological complexities of parasitology research. The epistemic valorization of in‑vitro organ‑on‑a‑chip platforms, though laudable, does not yet capture the immunological intricacies necessary for translational fidelity. A rigorous risk‑benefit calculus must incorporate quantitative metrics of pathogen virulence, vector competence, and host‑immune modulation. Moreover, the discourse neglects the exigency of genomic editing tools in elucidating parasite‑host interaction pathways, which, if wielded responsibly, could precipitate unprecedented therapeutic breakthroughs. In sum, the article's checklist, while comprehensive, requires iterative refinement grounded in systems biology and biosecurity heuristics.

L TaylorNovember 1, 2025 AT 18:43

one can wonder about the deeper meaning of skin as a boundary between self and other it is both a shield and a gateway the parasite exploits and the researcher studies this tension reveals a microcosm of our own vulnerability and curiosity

Matt ThomasNovember 10, 2025 AT 06:43

i get it mate but ur talkin about deep philosophey while the real issue is that labs still use mice for these itchy critters and they dont even give them proper painkillers u gotta stop the cruelties bro and use chip tech already

Nancy ChenNovember 18, 2025 AT 18:43

They don’t tell you that the big pharma giants have secret labs where they spin these parasites into bioweapon prototypes, hidden behind layers of NDA and "research" jargon. The public is kept in the dark while shadowy contracts fund covert experiments. Every time they mention "dual‑use" you should picture covert ops, not just academic caution. The community advisory boards are often puppet panels, bought off with token health grants. Remember, the very worms that crawl under our skin could be weaponized to destabilize nations. Trust no one when they claim it’s all for the greater good; the agenda is always about power and profit.

Beverly PaceNovember 27, 2025 AT 06:43

Ethics aren’t optional, they’re mandatory.

RALPH O'NEILDecember 5, 2025 AT 18:43

I appreciate the thorough checklist; it offers a solid framework for balancing scientific ambition with responsible conduct.

Mark WellmanDecember 14, 2025 AT 06:43

yeah its a good list but lets be real most labs just skim it and move on the paperwork is a pain and the real work is getting those parasites into the skin without getting a bite from a lab rat or a late night injury you know the grind is real and ethics become a afterthought when the grant deadline looms

Carl BoelDecember 22, 2025 AT 18:43

From a national security perspective, the focus on parasite research must prioritize protecting our citizens from biothreats. Any laxity in biosafety or dual‑use oversight jeopardizes national resilience. We need stringent, standardized protocols across all institutions, not a patchwork of voluntary checklists. The scientific community must align with defense agencies to ensure that breakthroughs serve public health, not hostile actors.

Shuvam RoyDecember 31, 2025 AT 06:43

Thank you for highlighting those security concerns. It is essential that we foster collaboration between research institutions and defense experts while maintaining transparency and respecting ethical standards. By integrating rigorous oversight with open communication, we can advance scientific knowledge without compromising safety.

Jane GrimmJanuary 8, 2026 AT 18:43

While the preceding remarks are commendably courteous, one must critique the superficiality of their engagement with the ethical nuances presented. The discourse, though polite, skirts a thorough interrogation of the moral imperatives governing use of animal models and human subjects. Moreover, the reliance on generic terminology betrays a lack of depth in grappling with dual‑use dilemmas. In light of these observations, a more incisive, rigorously articulated position is warranted to advance the conversation beyond perfunctory acknowledgment.