When a generic drug company wants to prove their version of a medication works just like the brand-name version, they don’t just guess. They run a crossover trial design. This isn’t just a common method-it’s the gold standard for bioequivalence studies. More than 89% of generic drug approvals by the FDA in recent years used this approach. Why? Because it’s the most efficient, accurate, and statistically powerful way to compare two versions of the same drug in real people.

How a Crossover Trial Works

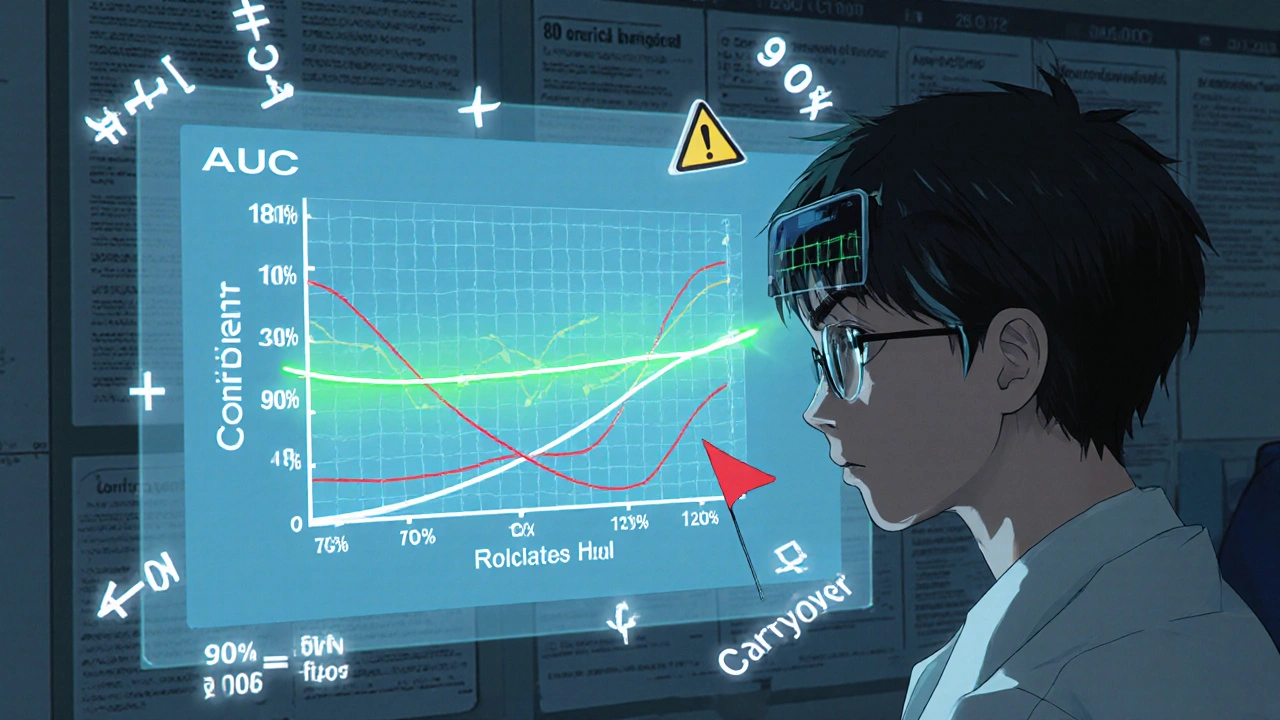

Imagine you’re testing two painkillers: Drug A (the brand) and Drug B (the generic). In a crossover trial, each volunteer takes both drugs-but not at the same time. One group gets Drug A first, then Drug B after a break. The other group gets Drug B first, then Drug A. This is called a 2×2 crossover: two treatments, two sequences, two periods. The key is the washout period between doses. This break-usually five times the drug’s elimination half-life-is critical. It ensures the first drug is completely out of the system before the second one starts. If you skip this, leftover drug from the first period can mess up the results. That’s called a carryover effect, and it’s one of the biggest reasons bioequivalence studies fail. Each person becomes their own control. That’s the magic. Instead of comparing a group of 24 people who took Drug A to a different group of 24 who took Drug B (a parallel design), you compare how each person responds to both. This removes noise from individual differences-age, weight, metabolism, genetics-and focuses only on the drug itself.Why It’s More Efficient Than Parallel Designs

A parallel design needs way more people to get the same level of confidence. If the differences between people are twice as big as the natural variation in how one person responds to the same drug, a crossover study needs only one-sixth the number of participants. That’s huge. For example, a study on generic warfarin (a blood thinner) used a 2×2 crossover with just 24 volunteers. A parallel design for the same drug would have needed 72 people. That’s a savings of nearly $300,000 and eight weeks of study time. That’s why most generic drug makers choose this method. But it’s not all easy wins. Crossover trials take longer. Each person is studied twice. Blood samples are drawn more often-sometimes 15-20 times per period. The whole process can stretch over weeks instead of days. But the trade-off is worth it: smaller sample size, higher precision, lower cost.What Happens With Highly Variable Drugs?

Not all drugs behave the same. Some, like warfarin or certain epilepsy meds, show big swings in how they’re absorbed from person to person. These are called highly variable drugs. Their intra-subject coefficient of variation (CV) is over 30%. For these, the standard 2×2 design isn’t enough. That’s where replicate designs come in. Instead of just two periods, you get four. Common setups include:- TRTR / RTRT (full replicate): each drug given twice

- TRR / RTR / TTR (partial replicate): test drug once, reference twice

Regulatory Rules You Can’t Ignore

The FDA and EMA don’t leave this to chance. Their guidelines are strict. The FDA’s 2013 guidance says crossover designs are recommended for bioequivalence studies. The EMA’s 2010 guideline is even more specific: washout must exceed five half-lives, and sequence effects must be tested statistically. Bioequivalence is proven when the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means (test/reference) falls between 80% and 125% for both AUC (total exposure) and Cmax (peak concentration). For highly variable drugs, the limits widen-but only if you use a replicate design and prove the drug’s variability is real. Missing these rules is a common reason for rejection. In 2018, 15% of failed submissions had inadequate washout periods. Others messed up the statistical model or didn’t account for period effects. One statistician on ResearchGate lost $195,000 because they didn’t validate the washout for a drug with a 12-hour half-life. They assumed five half-lives meant 60 hours. The drug lingered. Results were invalid. The study had to be redone.

How the Data Is Analyzed

This isn’t simple math. It’s advanced statistics. The standard model uses linear mixed-effects regression, often run in SAS using PROC MIXED. The model checks for three things:- Sequence effect: Did the order of drugs affect the outcome?

- Period effect: Did time itself (e.g., seasonal changes, fasting status) influence results?

- Treatment effect: Is there a real difference between the two drugs?

What’s Changing in 2025?

The field is evolving. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now allows 3-period replicate designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs (like digoxin or levothyroxine), where even tiny differences can be dangerous. The EMA is expected to update its guideline in late 2024, making full replicate designs the preferred method for all highly variable drugs. Adaptive designs are also gaining ground. Some studies now use a two-stage approach: start with a small group, check the variability, then decide whether to add more participants. In 2022, 23% of FDA submissions used this method-up from 8% in 2018. Still, the 2×2 crossover remains the workhorse. For 68% of standard bioequivalence studies, it’s all you need. It’s fast, cheap, and reliable-if done right.When Crossover Doesn’t Work

There are limits. If a drug’s half-life is longer than two weeks, a washout period would take months. That’s not practical. Patients can’t wait that long. In those cases, parallel designs are the only option. Crossover also isn’t used for drugs with irreversible effects-like chemotherapy or vaccines. Once you’ve given it, you can’t undo it. And it’s not suitable for chronic conditions where the drug’s effect builds over time. But for most oral solid dosage forms-pills, capsules, tablets-crossover is king.

Real-World Impact

This isn’t just academic. Bioequivalence studies mean patients get affordable medicines. A generic version of a brand-name statin can cost 90% less. That’s thousands of dollars saved per patient per year. Crossover designs make that possible. They reduce the cost and time of bringing generics to market without sacrificing safety or effectiveness. When done correctly, they’re one of the most elegant applications of statistics in medicine.What to Watch For

If you’re reviewing a bioequivalence study, ask:- Was the washout period validated? Was it longer than five half-lives?

- Was a sequence effect tested? Was it statistically significant?

- For highly variable drugs, was a replicate design used?

- Did they use the correct statistical model? Was missing data handled properly?

- Is the 90% CI for AUC and Cmax within the right limits?

What is the most common crossover design used in bioequivalence studies?

The most common design is the two-period, two-sequence (2×2) crossover, where participants receive either the test drug then the reference (AB), or the reference then the test (BA). This design is used in about 68% of all bioequivalence studies because it’s efficient, cost-effective, and meets regulatory standards for most drugs.

Why is a washout period so important in a crossover trial?

The washout period ensures the first drug is completely cleared from the body before the second drug is given. If it’s too short, residual drug from the first period can affect the results of the second-this is called a carryover effect. Regulatory agencies require washout periods to be at least five elimination half-lives of the drug. Failure to validate this is the most common reason for study rejection.

What’s the difference between a 2×2 and a replicate crossover design?

A 2×2 design gives each participant each drug once, in two periods. A replicate design (like TRTR/RTRT or TRR/RTR) gives each drug twice, across four periods. Replicate designs are used for highly variable drugs (CV >30%) because they let researchers measure within-subject variability, which is needed for reference-scaled bioequivalence (RSABE) and wider acceptance limits.

How many subjects are needed for a crossover bioequivalence study?

For a standard 2×2 crossover, sample sizes typically range from 12 to 48 subjects, depending on the drug’s variability. For highly variable drugs using a replicate design, you’ll need 24 to 72 subjects. The higher number is offset by the ability to use wider bioequivalence limits, which increases the chance of approval.

Can crossover designs be used for all types of drugs?

No. Crossover designs are not suitable for drugs with very long half-lives (over two weeks), irreversible effects (like chemotherapy), or those that cause permanent changes (like vaccines). They’re best for oral solid dosage forms with short to moderate half-lives where the drug can be safely administered multiple times.

What happens if a subject drops out during a crossover study?

If a participant drops out after the first period, their data is usually excluded from the analysis. Crossover designs rely on within-subject comparisons, so incomplete data breaks the self-matching logic. This is why dropout rates are closely monitored-high attrition can invalidate the study’s statistical power.

12 Comments

Cynthia SpringerNovember 26, 2025 AT 12:21

Okay but has anyone actually seen a 2×2 crossover study where the washout wasn’t just a guess? I’ve read papers where they say ‘five half-lives’ but the half-life was estimated from in vitro data. That’s not validation-that’s wishful thinking.

And don’t even get me started on how some CROs use the same blood collection schedule for every drug, regardless of pharmacokinetics. It’s lazy. And expensive. And honestly, it’s why so many generics get flagged later.

Aaron WhongNovember 27, 2025 AT 17:49

The elegance of the crossover design lies not in its statistical power, but in its ontological humility-it refuses to treat subjects as interchangeable units, instead honoring the singular phenomenology of each individual’s metabolic landscape.

By forcing the subject to become their own control, we are not merely measuring drug exposure-we are interrogating the very temporality of pharmacokinetic being. The washout period? A metaphysical pause. The sequence? A hermeneutic loop. And the 90% CI? The ethical boundary between equivalence and epistemic arrogance.

Ali MillerNovember 29, 2025 AT 13:36

USA still leads in bioequivalence innovation. Europe? Still stuck in 2010 guidelines. China? Doesn’t even validate washout periods properly. And don’t get me started on India-half their submissions use ‘approximate’ half-lives from PubMed.

It’s a joke. We spend billions to make sure generics are safe, and then some foreign CROs cut corners because ‘it’s cheaper.’ If this keeps up, the FDA will have to start flagging every non-US study. #BioequivalenceIsAmerican

Brittany MedleyNovember 29, 2025 AT 22:09

Just wanted to add: if you’re doing a replicate design for a highly variable drug, always run a power analysis first. I’ve seen so many studies where they just copy-paste 24 subjects from a 2×2 template and assume it’ll work. Nope. For drugs with CV > 40%, you need at least 36–48 subjects even in a TRTR design. Otherwise, you’re gambling with regulatory approval.

Also-use Phoenix WinNonlin. Don’t try to roll your own R code unless you’ve published in JPBA. Trust me.

mohit passiNovember 30, 2025 AT 18:50

this is why generics are so cheap now 🙌 no one talks about how much this design saves lives, not just moneyjames thomasDecember 2, 2025 AT 11:53

Let’s be real-this whole system is rigged. The FDA ‘recommends’ crossover designs because Big Pharma owns the software licenses and the statisticians. Small companies? They can’t afford the SAS licenses or the 6-week training.

And don’t tell me it’s about ‘scientific rigor.’ Why is a 75–133% range okay for generics but never for brand-name drugs? Sounds like a loophole for them to charge more later. 🤔

Sanjay MenonDecember 3, 2025 AT 21:41

How quaint. You all treat this like it’s some sacred ritual of pharmacometrics. But let me ask you: how many of these studies actually replicate real-world adherence? Patients don’t take pills on a 12-hour schedule with fasting and IV catheters. We’re measuring idealized pharmacokinetics in a lab-bred utopia.

The 90% CI is a fiction. The washout? A polite lie. The ‘self-control’? A statistical mirage. We’re not proving bioequivalence-we’re performing a very expensive pantomime for regulators who don’t understand kinetics but know how to check boxes.

And yet, somehow, it works. That’s the real tragedy.

Deborah WilliamsDecember 5, 2025 AT 13:07

It’s fascinating how Western medicine treats the body as a black box to be statistically tamed, while traditional systems like Ayurveda or TCM have spent millennia observing how individuals respond uniquely to herbs and compounds.

Maybe the crossover design isn’t so revolutionary after all-it’s just the West finally catching up to the idea that people aren’t variables, they’re stories. And stories don’t fit neatly into SAS output.

Still, I’m glad we’re at least trying to listen now.

Marissa CorattiDecember 7, 2025 AT 01:33

Let me take a moment to emphasize the monumental significance of this methodological framework-not merely as a regulatory tool, but as a paradigm-shifting triumph of experimental design in clinical pharmacology. The very notion of within-subject comparison, when juxtaposed against the chaotic heterogeneity of human physiology, represents an unparalleled epistemic refinement of observational science.

Moreover, the strategic implementation of reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE) for highly variable drugs, particularly when calibrated through full replicate designs such as TRTR/RTRT, constitutes not only a statistical innovation but a moral imperative: ensuring equitable access to life-sustaining therapeutics without compromising the integrity of pharmacokinetic validation.

It is, quite frankly, one of the most elegant applications of inferential statistics in modern medicine, and I am profoundly grateful to the biostatisticians, clinical pharmacologists, and regulatory scientists who have dedicated their careers to perfecting this delicate balance between rigor and accessibility.

May we never revert to the inefficient, underpowered, and ethically dubious parallel designs of the past.

With deepest respect,

-Marissa

Asia RovedaDecember 8, 2025 AT 12:34

Wait-so you’re telling me the FDA lets companies use 75–133% for some drugs? That’s not bioequivalence, that’s bio-anything.

And they’re calling this ‘science’? I’ve seen patients switch to generics and have seizures. They don’t test for that. They test for AUC and Cmax. But what about the 10% of people who metabolize drugs 5x slower? They don’t care.

This whole system is a lie. And you’re all just repeating the script.

Rachel WhipDecember 8, 2025 AT 23:46

Just a quick note for anyone reading this: if you’re planning a study and your drug has a half-life over 8 hours, please, please, please run a pilot to measure actual clearance in your population. Don’t rely on literature values.

I once reviewed a submission where they used a 60-hour washout for a drug with a 12-hour half-life… but the population had renal impairment. Their actual half-life was 36 hours. The carryover was massive. They didn’t even test for it.

It’s not just about following guidelines-it’s about understanding your subjects.

Micaela YarmanDecember 10, 2025 AT 06:12

As someone who grew up in a country where generic medicines are the only option, I want to say thank you to the scientists who made this possible.

This isn’t just about statistics or regulatory boxes. It’s about a diabetic in rural India getting insulin for $5 instead of $500. It’s about a grandmother in Ohio keeping her blood pressure under control without choosing between meds and groceries.

Yes, the design is complex. Yes, the math is intense. But the outcome? Human. And that’s what matters most.