When you get older, the way your body handles medicines changes - and the side effects can feel a lot worse. In fact, older adults are more than twice as likely to experience severe drug reactions compared to younger people. Understanding why this happens, which drugs are most risky, and what clinicians can do to keep you safe is the key to better tolerability.

Why Age Matters: The Science of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics

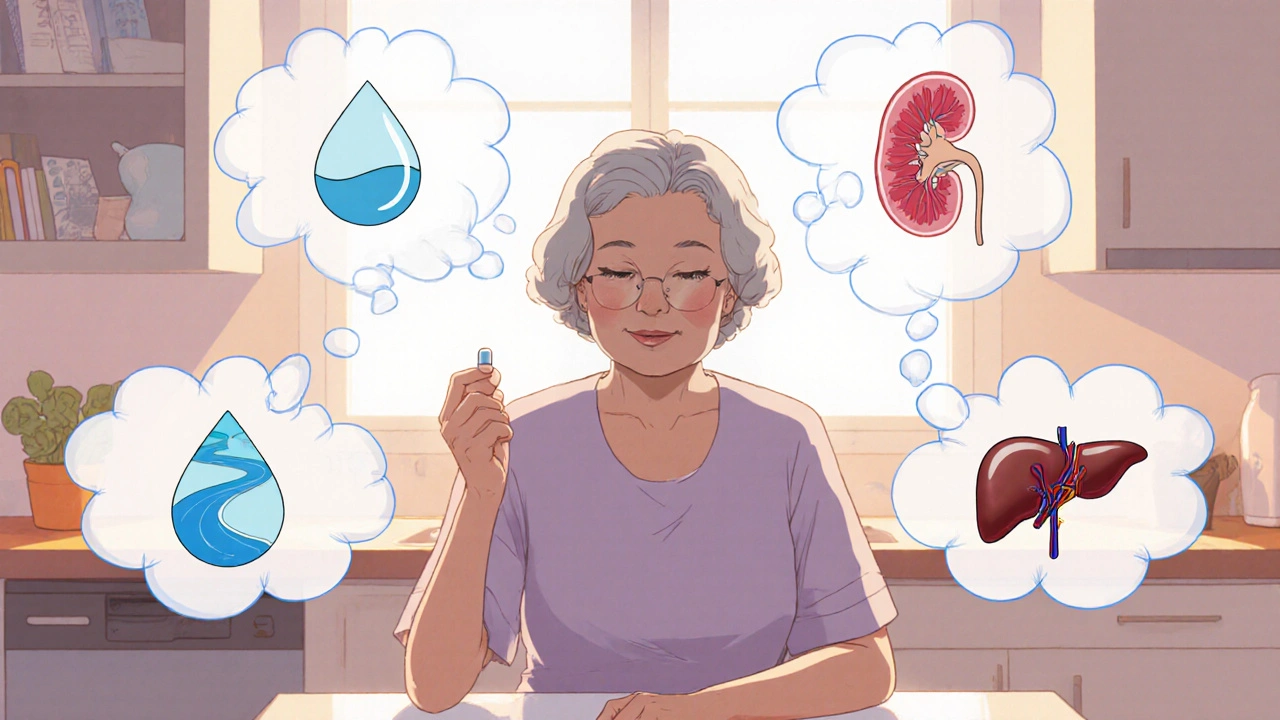

Medication side effects in older adults are driven by two core processes: how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and excretes drugs (pharmacokinetics) and how the drug’s action changes at the cellular level (pharmacodynamics). Both start shifting around age 65 and become more pronounced with each decade.

- Body composition: Total body water drops ~15% between ages 25‑80, while body fat rises to about 40% in men and 48% in women. Lipid‑soluble drugs linger longer, whereas water‑soluble meds have a smaller distribution pool.

- Kidney function: Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) falls about 0.8 mL/min/1.73 m² per year after age 40. This slows clearance of renally eliminated drugs like digoxin and many antibiotics.

- Liver blood flow: Declines 20‑40% by age 65, reducing first‑pass metabolism for meds such as propranolol and verapamil.

- Protein binding: Serum albumin drops 10‑15%, raising the free fraction of highly bound drugs (e.g., warfarin).

- Receptor sensitivity: Older brains become more sensitive to sedatives, so a standard dose of diazepam can cause 50% more sedation.

These shifts mean the same tablet can produce a higher effective concentration, longer exposure, or stronger physiological response in an 80‑year‑old than in a 30‑year‑old.

Common Drug Classes That React Differently With Age

Here’s a quick look at the big hitters that tend to bite harder when you’re older.

| Drug Class | Typical Age‑Related Issue | Adjustment Guideline |

|---|---|---|

| Anticholinergics (e.g., diphenhydramine) | 4‑fold higher delirium risk in >75 y | Use non‑sedating alternatives; avoid if possible |

| Warfarin | 20‑30% lower dose needed; INR instability ↑ | Start at 0.5× usual dose; monitor INR weekly |

| Benzodiazepines (e.g., lorazepam) | 2‑3× fall risk; prolonged sedation | Prefer short‑acting agents or non‑benzodiazepine sleep aids; limit to ≤2 weeks |

| Beta‑blockers (e.g., propranolol) | 50% higher plasma level needed for same effect | Start low, titrate slowly; watch heart rate |

| Antihypertensives | Orthostatic hypotension ↑ (28% >80 y) | Lower initial dose; assess standing BP |

| Opioids (e.g., fentanyl) | 30‑50% lower dose for equal sedation | Start at 25% standard dose; monitor respiration |

These adjustments aren’t just “nice to have” - they’re built into the Beers Criteria and the STOPP/START criteria, which list over 50 potentially inappropriate meds for the elderly.

Real‑World Impact: Numbers That Matter

Numbers drive the point home:

- ≈35% of hospital admissions for adults > 65 y are medication‑related (National Institute on Aging, 2022).

- 48% of seniors take five or more prescriptions, creating polypharmacy that spikes ADR risk.

- Every $1 billion spent on preventable ADRs in the U.S. translates to 15% of total medication costs for older adults.

When you combine altered drug handling with multiple meds, the chance of a bad reaction climbs dramatically.

How Clinicians Reduce Risks

Doctors and pharmacists use a toolbox of strategies to keep side effects in check.

- Start low, go slow: Initial doses are often 25‑50% of the adult standard for renally cleared drugs.

- Regular medication reviews: Every 3‑6 months, clinicians run a Brown Bag Review, asking patients to bring all pills, OTCs, and supplements.

- Use eGFR, not serum creatinine alone, to guide dose cuts for kidney‑impacted meds.

- Apply STOPP/START criteria: Flag drugs to stop (e.g., long‑acting anticholinergics) and identify omissions (e.g., calcium‑vitamin D for osteoporosis).

- Deprescribing initiatives: Aim to drop 30‑50% of non‑essential meds in nursing‑home residents.

- Pharmacogenomic testing: For psychotropics, checking CYP2D6/CYP2C19 can cut ADRs by a third.

These steps have been shown to reduce adverse events by 22% in controlled trials.

Patient Stories: What It Looks Like on the Ground

Numbers become personal when you hear from patients:

- Emily, 78, stopped taking an antihistamine after a week because “it made me feel foggy all the time.”

- Robert, 82, fractured his hip after his blood‑pressure pill caused severe orthostatic dizziness - a dose meant for a 50‑year‑old.

- Maria, 75, switched from a high‑dose opioid to a low‑dose patch after her doctor realized her liver blood flow had dropped, cutting her risk of respiratory depression.

These anecdotes echo the survey data: 68% of seniors report dizziness or falls related to meds, and 45% admit they quit a drug because the side effects outweighed the benefit.

Looking Ahead: Precision Geriatric Pharmacology

The future is moving toward truly personalized dosing. The National Institute on Aging is pouring $127 million into research on age‑specific PK/PD changes. AI tools like MedAware already flag dosing errors in real‑time, cutting mistakes by over 40%. Pharmacogenomics, sex‑specific dosing, and even wearable‑based renal monitoring are on the horizon, promising a 50% drop in preventable ADRs by 2035.

Until those technologies become routine, the best defense remains vigilance: knowing the drugs that pose the biggest risk, reviewing meds often, and speaking up when side effects feel out of whack.

Key Takeaways

- Age‑related changes in body composition, kidney and liver function, and receptor sensitivity make older adults far more vulnerable to medication side effects.

- High‑risk classes include anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, certain opioids, and many cardiovascular drugs.

- Tools like the Beers Criteria, STOPP/START criteria, and regular Brown Bag Reviews help clinicians tailor therapy.

- Polypharmacy is a major driver of adverse events; deprescribing can cut unnecessary drug exposure by up to half.

- Emerging precision tools-AI alerts, pharmacogenomics, and better trial inclusion-will further improve tolerability for seniors.

Why do older adults experience more side effects from the same medication dose?

Because aging changes how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and excretes drugs, and it also makes tissues more sensitive to drug actions. Less water, more fat, reduced kidney filtration, and slower liver blood flow all raise drug levels, while brain receptors become more reactive, so a dose that’s safe for a 30‑year‑old can feel like a strong hit for a 75‑year‑old.

What is the “start low, go slow” rule?

It means prescribing about 25‑50% of the usual adult dose for a new medication, then increasing gradually while monitoring for side effects or lab changes. This approach accounts for reduced clearance and higher sensitivity in older patients.

Which medications should be avoided altogether in seniors?

The Beers Criteria lists over 50 drugs to avoid or use with extreme caution, including long‑acting anticholinergics, non‑selective NSAIDs, certain antihistamines, and many benzodiazepines. Checking the latest Beers update (2023) is the quickest way to spot these high‑risk agents.

How often should a senior have a medication review?

Guidelines recommend every 3‑6 months, and any time a new drug is added, a dose changes, or a health event (like a fall) occurs. The review should include prescription, over‑the‑counter, and supplement lists.

Can genetic testing really reduce side effects?

Yes. For drugs metabolized by enzymes like CYP2D6 or CYP2C19, a simple saliva test can tell whether a patient is a poor or ultra‑rapid metabolizer. Adjusting the dose based on this information has been shown to cut adverse drug reactions by up to 35% in older adults taking antidepressants or pain meds.

12 Comments

Ben DurhamOctober 26, 2025 AT 18:33

Reading through the pharmacokinetic shifts really makes you appreciate how much our bodies change over the years. The drop in total body water and the rise in fat really means lipophilic drugs stick around longer. I’ve seen seniors on diphenhydramine get super drowsy, which lines up with the anticholinergic risks you highlighted. It also reminds me to always ask my older relatives about any over‑the‑counter meds they might be taking. A quick Brown Bag Review can catch a lot of hidden interactions. It’s good to see the emphasis on starting low and going slow – that’s a solid safety net. Overall, the piece is a decent refresher on why we need to be extra careful with dosing in the elderly.

Gary CampbellOctober 27, 2025 AT 22:20

The pharma industry doesn’t want you to know how they manipulate the data on drug safety for seniors. They push high‑dose antihistamines because they profit from the sheer volume of sales, ignoring the 4‑fold higher delirium risk after 75. The so‑called "Beers Criteria" is just a band‑aid, not a solution; the real problem is that big pharma funds the panels that write those guidelines. They hide the fact that kidney function declines faster than reported, so dosing calculators are often off by a factor of two. You’ll also notice the selective citation of studies that favor their products, while negative outcomes get buried. The AI tools like MedAware sound promising, but they’re owned by the same corporations that market the drugs. Remember, every time a new drug hits the market, it’s first tested on younger, healthier volunteers, not on the real‑world elderly population. The omission of geriatric pharmacogenomics in trial designs is a glaring oversight that benefits the bottom line. And let’s not forget the influence of lobbying on Medicare policies, which keeps expensive, risky medications in the formulary. In short, the system is set up so that seniors become the testing ground for side‑effects while the profits go to shareholders.

renee granadosOctober 28, 2025 AT 12:13

That warning about anticholinergics hitting harder is spot on. I’ve seen my grandma get confused after a night dose of diphenhydramine. The brain gets extra fog because the drug hangs around due to less water in her body. Switching to a non‑sedating antihistamine helped her sleep better without the haze. It’s simple: older bodies handle meds differently, so we must be vigilant.

Stephen LenzovichOctober 29, 2025 AT 02:06

Honestly, all this “start low, go slow” talk is just bureaucratic nonsense that slows down treatment for real patriots who need to stay sharp. If you’re over 65 and still want to fight for your country, you shouldn’t be babysitted by doctors over a tiny dose of beta‑blockers. The body can adapt, and the guidelines are made by out‑of‑touch elites. Let’s not forget that many of these so‑called risky meds, like propranolol, have kept generations healthy on the front lines. We need to trust our own resilience, not hide behind tables of adjustments.

Barna BuxbaumOctober 30, 2025 AT 05:53

Hey folks, just wanted to add that keeping a medication list up‑to‑date is a game‑changer. I help my neighbors do a Brown Bag Review every few months, and we’ve caught duplicate prescriptions and OTC conflicts that were causing dizziness. It's also a great excuse to chat with the pharmacist about newer, safer alternatives. Small steps like this can dramatically cut down on those scary side‑effects.

Alisha CervoneOctober 30, 2025 AT 19:46

Looks good but a lot of words. Could be shorter.

Diana JonesOctober 31, 2025 AT 09:40

Wow, this is a masterclass in geriatric pharmacology, folks! Let’s break down the jargon: The “first‑pass metabolism” is basically your liver's first line of defense, and when it slows down, drugs like propranolol linger like an uninvited party guest. The STOPP/START criteria? Think of them as the bouncer that decides which meds get kicked out of the club. Polypharmacy is a word that sounds sophisticated but it simply means “too many pills,” and that’s a recipe for a side‑effect fiasco. If you’re on an opioid, you’re basically walking a tightrope – a 25% starting dose is the safety net that keeps you from falling off. And for the love of all things clinical, schedule that medication review every quarter; it’s the only way to keep the list from turning into a novel. Bottom line: treat your older patients like you’d treat a high‑performance engine – regular tune‑ups, quality fuel, and no dangerous additives.

Carolyn CameronOctober 31, 2025 AT 23:33

In light of the preceding discourse, one must acknowledge the paramount importance of adhering to the Beers Criteria, an illustrious compendium of evidence‑based recommendations. The salient point, undeniably, is the necessity for clinicians to meticulously evaluate the pharmacodynamic implications inherent in geriatric pharmacotherapy. It is incumbent upon the medical community to integrate these guidelines with unwavering fidelity, thereby mitigating the pernicious incidence of adverse drug reactions among the elderly populace.

Joe LangnerNovember 1, 2025 AT 13:26

Yo, the whole med review thing is actually pretty simple. I usually just grab a notebook and write down every pill, even the chewable vitamins. Then I call the doc, ask if any can be dropped – like half the time we find a med that’s been there for years but isn’t needed. I’m not a doc, but it saved my dad from a nasty fall 'cause his blood pressure med was too high. Same thing with my aunt, we cut her anti‑histamine, she stopped feeling foggy. It’s cool how a few minutes of checking can spare a whole hospital stay.

naoki doeNovember 2, 2025 AT 17:13

People should stop being so scared of side effects and just take the meds. The risks are exaggerated and doctors are just trying to push their own agendas. If you’re over 65 and still want to live, you need to keep taking whatever they prescribe without question.

sarah basaryaNovember 3, 2025 AT 07:06

Wow, look at all these fancy terms! It’s like reading a textbook from 1999. I can’t believe people actually use that kind of language on a casual forum. Anyway, it’s clear the article is trying hard to sound important, but the core message is just, “don’t give seniors too much medicine.” Simple as that.

Samantha TaylorNovember 3, 2025 AT 21:00

Ah, the classic ‘let's trust the system’ line-how original. Of course, the pharma giants will keep pushing dangerous drugs while hiding the real data behind a veil of jargon. It's almost comedic how they present “evidence‑based” guidelines as if they weren’t swayed by big money. Meanwhile, seniors keep paying the price, literally and figuratively. One would think we’d have learned by now, but no, we’re still dancing to the same old tune.