One in every 20 children has a vision problem that could lead to permanent vision loss-if it’s not caught early. Most parents assume their child sees fine because they navigate the house, recognize faces, or watch cartoons without issue. But vision isn’t just about seeing letters on a chart. It’s about the brain learning to interpret what the eyes send. And if that learning gets interrupted before age 7, the damage can be permanent.

Why Screening Before Age 5 Matters

The visual system in young children is still developing. Light enters the eye, but the brain must learn to connect that input with meaning. If one eye is blurry, misaligned, or blocked by a cataract, the brain starts ignoring signals from that eye. That’s amblyopia-lazy eye. It’s not a problem with the eye itself. It’s a problem with the brain’s wiring.Studies show that when amblyopia is detected before age 5, 80 to 95% of children can regain normal vision with treatment. That number drops to just 10 to 50% if treatment starts after age 8. That’s not a small difference. That’s life-changing. Strabismus-where the eyes don’t line up-often causes amblyopia too. And refractive errors like nearsightedness, farsightedness, or astigmatism can hide in plain sight. A child might squint to see the TV, but never say anything because they don’t know what normal vision feels like.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force gives pediatric vision screening a Grade B recommendation: strong enough to say it should be routine. They specifically recommend screening all children between ages 3 and 5. That’s not a suggestion. It’s a medical standard backed by decades of research.

How Screening Works at Different Ages

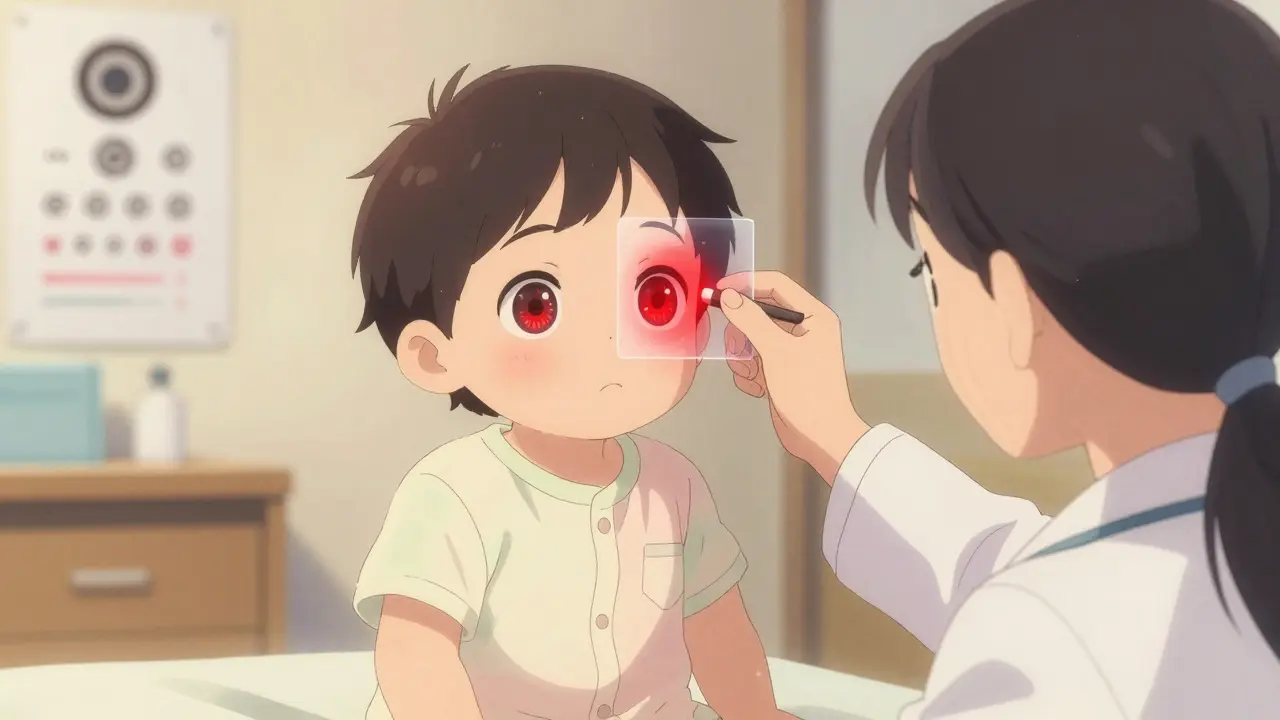

Screening isn’t one-size-fits-all. The method changes as the child grows.Infants (0-6 months): The red reflex test is the first line. A doctor shines a light into each eye using an ophthalmoscope. A healthy eye reflects a bright red glow. If one eye looks dark, white, or uneven, it could mean a cataract, retinoblastoma (a rare eye tumor), or other serious issue. This test takes seconds and can catch problems before a baby even smiles.

6 months to 3 years: Red reflex testing continues, along with checking how the eyes move together and whether the eyelids or lashes are blocking vision. At this age, kids can’t read letters, so providers watch for eye tracking, pupil response, and whether one eye turns in or out.

Age 3 and up: This is where visual acuity testing begins. Instead of letters, kids use symbols: circles, squares, apples, or the letters H, O, T, V. These are easier for young minds to recognize. The child points to a matching card or says what they see. The test is done one eye at a time, with the other covered. The chart is placed 10 feet away, and the child must correctly identify the majority of symbols on the 20/50 line at age 3, 20/40 at age 4, and 20/32 by age 5.

Some clinics now use instrument-based screens-devices like the SureSight, Retinomax, or blinq™ scanner. These handheld tools flash light into the eyes and measure how light reflects back to detect refractive errors or misalignment in under a minute. They don’t need the child to say anything. That’s a game-changer for toddlers who won’t sit still.

Instrument-Based vs. Chart-Based Screening

There’s a real debate in pediatric eye care: which method is better?Chart-based tests (like LEA Symbols or HOTV) are the gold standard for kids who can cooperate. They’re cheap, reliable, and don’t need batteries. But they fail when the child is scared, tired, or just doesn’t understand. About 1 in 5 three-year-olds won’t complete the test.

Instrument-based screens fix that. They work on sleeping babies, autistic children, and non-verbal kids. The blinq™ scanner, FDA-cleared in 2018, has 100% sensitivity for detecting referral-worthy conditions in kids aged 2-8. That means it rarely misses a problem. But it can sometimes flag kids who don’t actually need treatment-false positives. That’s why experts still recommend chart testing for kids who can do it.

The American Academy of Pediatrics says instrument-based screening is the standard of care for children aged 3-5, especially in busy clinics. But they also say: don’t skip the chart test if the child can do it. Use both if you can.

Who Should Be Screening and How

Pediatricians, family doctors, nurses, and even school staff can do vision screening. You don’t need an ophthalmologist. But you do need training.Proper technique matters. If the chart isn’t at the right height, or the room is too dark, or the distance is off by a foot, you’ll get wrong results. A 2018 study found 25% of screenings had lighting issues. Another 20% had incorrect distance measurements. That’s not incompetence-it’s lack of training.

The National Center for Children’s Vision and Eye Health offers free online modules. They cover everything from how to hold an occluder to interpreting autorefractor readings. Over 15,000 providers have completed them since 2016. It takes 2-4 hours. That’s less time than a typical well-child visit.

Screening should happen at every well-child visit from age 1 onward. The AAP’s Bright Futures schedule recommends checks at 8, 10, 12, and 15 years too. But the most critical window is 3-5 years. That’s when the brain is still rewiring itself to fix vision problems.

What Happens After a Positive Screen

A failed screen doesn’t mean your child is blind. It means they need a full eye exam by an optometrist or pediatric ophthalmologist.Most children who fail screening have treatable issues. Glasses can fix blurry vision. Patching the stronger eye for a few hours a day can train the weaker one. Surgery can correct crossed eyes. The key is speed. The longer you wait, the harder it gets.

Referral should happen within 1-2 weeks. Delays are common-parents think it’s not urgent, or they wait for a routine checkup. But vision isn’t like a cold. It doesn’t get better on its own.

And here’s the hard truth: kids from low-income families, Black and Hispanic children, and those in rural areas are 20-30% less likely to get screened. That’s not a gap in access. That’s a gap in equity. Screening programs need to reach these communities with mobile units, school partnerships, and culturally competent outreach.

The Bigger Picture: Cost and Impact

Some say vision screening is expensive. But consider this: untreated amblyopia leads to lifelong vision loss. That means higher rates of accidents, lower educational achievement, reduced job opportunities, and increased reliance on social services.The USPSTF calculated that every dollar spent on pediatric vision screening saves $3.70 in lifetime costs. That’s $1.2 billion a year in the U.S. alone. And that doesn’t even count the emotional toll on families.

Equipment costs are rising-autorefractors run $5,500 to $8,500. But many clinics share devices. Medicaid and private insurers cover screening under the Affordable Care Act’s pediatric essential health benefits. And 38 states require vision screening before school entry, though standards vary wildly.

AI is coming. The blinq™ scanner uses machine learning to analyze eye reflections faster and more accurately than ever. New research is testing screening as early as 9 months. Guidelines from the AAP are expected to update by 2025.

What Parents Should Do

You don’t need to be an expert. But you do need to ask.- Ask your pediatrician: "Is my child getting a vision screen at this visit?"

- If they say no, ask why. Is it because the child is too young? Too uncooperative? Then ask: "Can we use an instrument-based screen?"

- If your child fails, don’t wait. Get a full eye exam within two weeks.

- Watch for signs: squinting, head tilting, closing one eye to see, rubbing eyes constantly, or avoiding close-up tasks like books or puzzles.

- Even if your child passes, keep asking. Vision can change. Screening isn’t a one-time event.

Children don’t tell you their vision is blurry. They don’t know it should be different. That’s why adults have to be the ones who notice. And act.

At what age should pediatric vision screening start?

Vision screening should begin at the first well-child visit, usually around 6 months, with a red reflex test. Formal visual acuity screening starts at age 3, but instrument-based screening (like autorefractors) can be used as early as 1 year old, especially if the child isn’t yet able to cooperate with eye charts.

What happens if a child fails a vision screen?

A failed screen doesn’t mean the child has a permanent condition-it means they need a full eye exam by a pediatric optometrist or ophthalmologist. Most children who fail have treatable issues like refractive errors, amblyopia, or strabismus. Treatment may include glasses, patching, or surgery. The key is acting quickly, ideally within 1-2 weeks.

Are instrument-based screens better than eye charts?

For children under 5 who won’t cooperate with charts, instrument-based screens (like SureSight or blinq™) are more reliable and faster. They detect refractive errors and misalignment without needing the child to respond. But for cooperative children aged 5 and up, eye charts (LEA Symbols, HOTV) remain the gold standard. Experts recommend using both when possible.

Can vision problems be fixed after age 5?

Yes, but it’s harder. The visual system is most adaptable before age 5. After age 7, the brain’s ability to rewire itself drops sharply. Treatment after age 8 has only a 10-50% success rate compared to 80-95% when caught early. That’s why screening before age 5 is critical-not optional.

Is pediatric vision screening covered by insurance?

Yes. Under the Affordable Care Act, pediatric vision screening is an essential health benefit. Most private insurers and Medicaid programs cover screening during well-child visits. Some states also require school-entry screening. Check with your provider, but you should not be charged for screening during a routine checkup.

Why are some children less likely to get screened?

Children from low-income families, Black and Hispanic communities, and rural areas are 20-30% less likely to receive recommended vision screening. Barriers include lack of access to pediatric care, transportation issues, language differences, and unawareness of the importance. Targeted outreach, mobile clinics, and school-based programs are needed to close this gap.

Can a child outgrow a vision problem without treatment?

No. Conditions like amblyopia and strabismus won’t resolve on their own. The brain learns to ignore the weaker eye, and without intervention, that suppression becomes permanent. Even if the child seems to function fine, their depth perception and visual clarity are compromised. Early treatment is the only way to restore normal vision.

15 Comments

Glendon ConeDecember 31, 2025 AT 11:33

Just had my 4-year-old screened at the pediatrician using that blinq™ thingy-took 30 seconds, no crying, no fuss. Turned out she had mild astigmatism. Got glasses and now she’s obsessed with reading books. 🤯 Kids don’t know what normal is-so we gotta be the ones who notice. Thanks for this post, huge eye-opener.

kelly tracyJanuary 1, 2026 AT 15:43

Stop pushing screening like it’s some miracle cure. My cousin’s kid got flagged for amblyopia at age 3, spent two years in a patch, and still can’t catch a baseball. The whole system is overmedicalized. Let kids be kids. Not every squint needs a lab coat.

Kelly GerrardJanuary 1, 2026 AT 15:46

Screening before age five is not optional it is a medical imperative backed by decades of research and clinical evidence the data is clear and the consequences of inaction are irreversible

Henry WardJanuary 2, 2026 AT 07:18

Oh so now we’re diagnosing toddlers like they’re lab rats? Next they’ll be scanning newborns for ADHD. This is what happens when you let bureaucrats write healthcare policy. My daughter squints because she’s tired not because she’s broken.

Aayush KhandelwalJanuary 2, 2026 AT 20:07

Instrument-based screening is a paradigm shift in pediatric ophthalmology-autorefractors offer high-throughput, objective refractive error detection with sensitivity >95% in non-verbal cohorts. The real bottleneck isn’t tech-it’s provider training and systemic fragmentation in primary care workflows. We need embedded screening protocols, not ad hoc checklists.

Sandeep MishraJanuary 3, 2026 AT 14:44

It’s beautiful how a simple light test can change a child’s life. My nephew was diagnosed at 2 with a cataract thanks to red reflex screening-he’s now 8, plays soccer, reads chapter books. We just need more parents to ask the question. No child should grow up thinking the world is blurry.

Joseph CorryJanuary 5, 2026 AT 09:26

One must question the epistemological foundations of pediatric vision screening. Is the 80-95% recovery rate merely a statistical artifact of early intervention bias? Or is it an ideological construct reinforcing the medicalization of childhood development? The brain’s plasticity is not a lever to be pulled-it’s a mystery we’ve only begun to glimpse.

Colin LJanuary 5, 2026 AT 14:05

I remember when I was a kid, my dad used to say if you squinted hard enough, you could see anything. Well, turns out he was wrong. I had undiagnosed astigmatism until I was 17, failed my driver’s test twice, spent years with headaches, and now I wear thick glasses and still can’t read street signs at night. All because no one ever bothered to check. So yes, screen them. Screen them at six months. Screen them in the womb if you can. I’m not mad, I’m just… disappointed.

Hayley AshJanuary 5, 2026 AT 15:49

Oh great another government mandate disguised as ‘care’. Next they’ll mandate breathing tests for newborns. Can we please stop treating every kid like they’re a ticking time bomb? My son’s eyes work fine. He sees the TV just fine. Why do we need a machine to tell us that?

srishti JainJanuary 6, 2026 AT 01:02

Screening is useless if parents don’t follow up. My friend’s kid failed twice. She waited a year. Now the doc says patching won’t help. So yeah. Screen all you want. But don’t act surprised when nothing changes.

Cheyenne SimsJanuary 7, 2026 AT 15:34

Proper capitalization, punctuation, and grammatical structure are non-negotiable in public health communication. This post is well-researched and meticulously structured. It exemplifies the standard of clarity and precision that must be upheld in medical advocacy.

Shae ChapmanJanuary 8, 2026 AT 16:35

OMG I just cried reading this. My daughter had a lazy eye and we didn’t know until she was 5. Patching was the hardest thing ever-but seeing her see the stars for the first time? Worth every tear. 🥹❤️ Please, please, please ask your pediatrician. It takes seconds and changes everything.

Nadia SpiraJanuary 9, 2026 AT 13:14

Let’s be real-this is just another way for Big Ophthalmology to monetize pediatric care. Autorefractors cost $8K. Insurance pays for it. Parents panic. Kids get labeled. The real issue? We’ve lost trust in natural development. Maybe some kids just need to grow into their eyes.

henry mateoJanuary 9, 2026 AT 19:17

my kid passed the screen but i still took him to the eye doc anyway bc i noticed he kept tilting his head when he watched cartoons. turns out he had a tiny lazy eye. glad i trusted my gut. thanks for the post, really helped me feel less crazy.

Kunal KarakotiJanuary 11, 2026 AT 10:51

It’s fascinating how the human eye becomes a mirror of societal neglect. The child who sees poorly is not broken; the system that fails to see them is. Screening is not merely medical-it’s ethical. We measure vision in acuity, but perhaps we should also measure compassion in action.